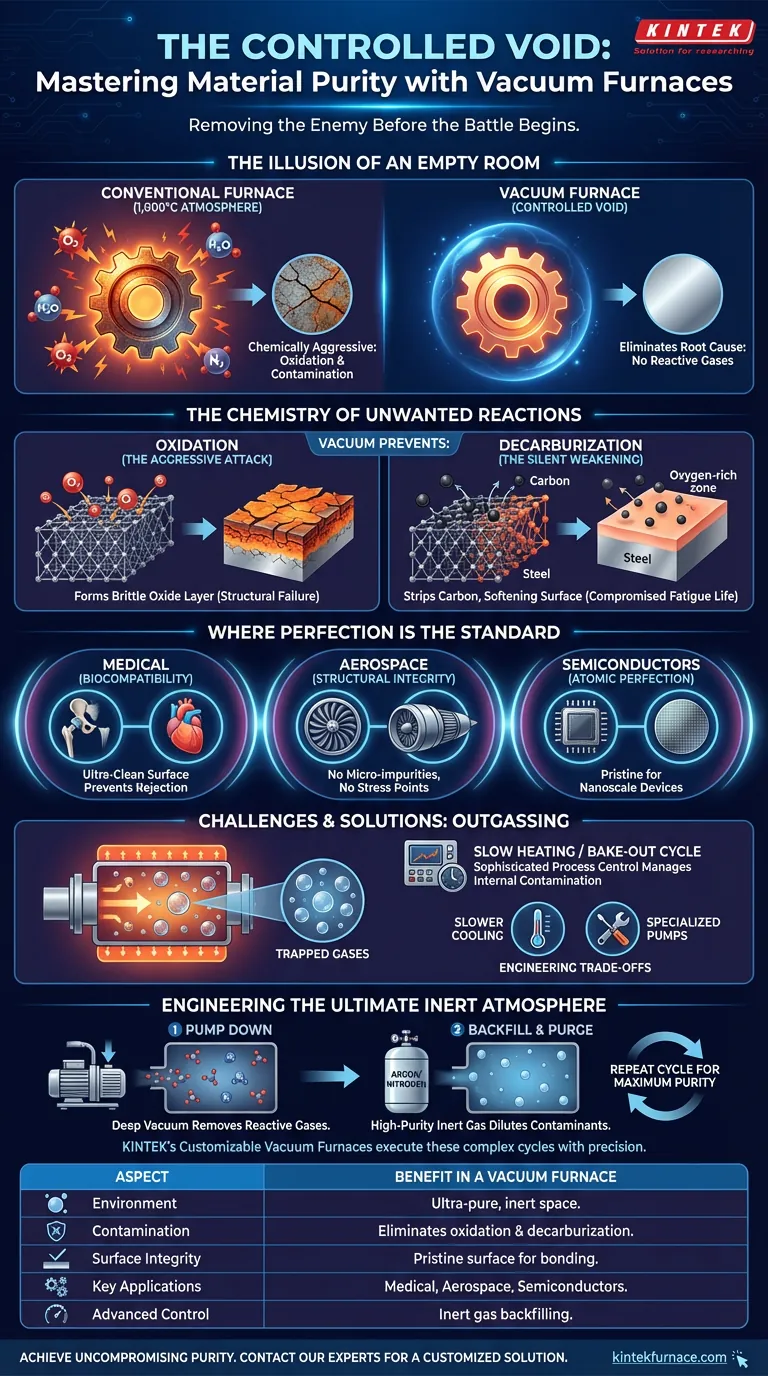

The Illusion of an Empty Room

The greatest threats in materials science are often invisible. At room temperature, the air around us seems harmless. But at 1,000°C, it becomes a chemically aggressive agent, eager to corrupt the materials we are trying to perfect.

A conventional furnace heats a material within this atmosphere. A vacuum furnace operates on a far more elegant principle: it removes the atmosphere entirely.

It’s the difference between fighting a battle and ensuring there is no enemy to fight in the first place. By creating a controlled void, we eliminate the root cause of contamination.

The Chemistry of Unwanted Reactions

High temperature is a catalyst for change. Without precise environmental control, that change is often for the worse. The primary goal of a vacuum is to prevent these unwanted chemical reactions.

Oxidation: The Aggressive Attack

Oxygen is relentless. At high temperatures, it aggressively bonds with a metal’s surface, forming a brittle, flaky oxide layer. This isn’t just a cosmetic issue; it's a structural failure in the making. A vacuum environment, by its very nature, is oxygen-free, providing a perfect shield against this attack.

Decarburization: The Silent Weakening

For high-strength steels, carbon is the source of hardness and resilience. But when heated in an oxygen-rich atmosphere, carbon atoms can be stripped from the surface, a process called decarburization. The result is a component that is deceptively soft on the outside, compromising its fatigue life and structural integrity.

By removing the reactive gases, a vacuum furnace ensures the material you put in is the material you get out—only better, without any unintended chemical alterations.

Where Perfection is the Only Standard

In some fields, "good enough" is a recipe for disaster. The purity achieved in a vacuum is not a luxury; it's a fundamental requirement.

-

Inside the Human Body: A medical implant, like a hip replacement, must be perfectly biocompatible. If its surface is even slightly oxidized, the human body may identify it as a foreign invader, leading to rejection. The ultra-clean surface from a vacuum furnace ensures the body accepts the implant as its own.

-

At 30,000 Feet: An aerospace turbine blade spins thousands of times per minute under immense heat and stress. A microscopic surface impurity—a tiny spot of oxidation—can become a stress concentration point, the origin of a crack that leads to catastrophic engine failure.

-

On the Nanoscale: Semiconductor manufacturing relies on atomic-level perfection. A single, unwanted particle or a thin oxide layer can ruin a complex microchip, rendering it useless. Vacuum processing is the standard for creating the pristine silicon wafers that power our digital world.

The Challenges of an Engineered Void

Creating a perfect vacuum is not without its complexities. Understanding them is key to mastering the process.

The Enemy from Within: Outgassing

Sometimes, the source of contamination is the material itself. As a part heats up, trapped internal gases can be released into the vacuum—a phenomenon called outgassing. These gases can then contaminate the part's surface.

Managing this requires sophisticated process control, like slow heating ramps or preliminary "bake-out" cycles. This level of control is a hallmark of well-engineered systems, where the furnace's capabilities are designed to anticipate and manage material behavior.

Process Trade-offs

A vacuum is a poor conductor of heat, which means cooling parts can be slower than in an atmosphere furnace. The high-performance pumps also require specialized maintenance. These aren't drawbacks, but rather engineering trade-offs for achieving an unparalleled level of purity.

Engineering the Ultimate Inert Atmosphere

For the absolute highest level of purity, a two-step process is often used.

- Pump Down: The chamber is pumped to a deep vacuum, removing the vast majority of reactive atmospheric gases.

- Backfill & Purge: The chamber is then backfilled with a high-purity inert gas, like argon or nitrogen. This dilutes any remaining contaminants.

Repeating this pump-and-purge cycle multiple times scrubs the environment clean, leaving a precisely controlled, perfectly inert space for thermal processing. Achieving this requires a furnace system engineered for this exact purpose. Products like KINTEK's customizable vacuum furnaces are designed to execute these complex, multi-stage cycles with precision, ensuring absolute purity for the most demanding applications.

| Aspect | Benefit in a Vacuum Furnace |

|---|---|

| Environment | Creates an ultra-pure, inert space by removing reactive gases. |

| Contamination | Eliminates oxidation and decarburization at the source. |

| Surface Integrity | Produces an ultra-clean, pristine surface essential for bonding. |

| Key Applications | Medical, aerospace, semiconductors, and advanced electronics. |

| Advanced Control | Enables inert gas backfilling for maximum purity protocols. |

Ultimately, choosing a vacuum furnace is a commitment to controlling every variable. It's an understanding that to build the future's most advanced materials, you must first create a perfect, controlled void.

If your work demands uncompromising purity and performance, achieving it begins with the right environment. Contact Our Experts to explore a customized furnace solution for your specific needs.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering and Brazing Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- 1200℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

Related Articles

- The Unseen Enemy: Why Vacuum Furnaces Are a Bet on Perfection

- Beyond the Heat: The Psychology of Perfect Vacuum Furnace Operation

- More Than a Void: The Inherent Energy Efficiency of Vacuum Furnace Design

- Beyond Heat: The Physics and Psychology of Vacuum Furnaces

- From Brute Force to Perfect Control: The Physics and Psychology of Vacuum Furnaces