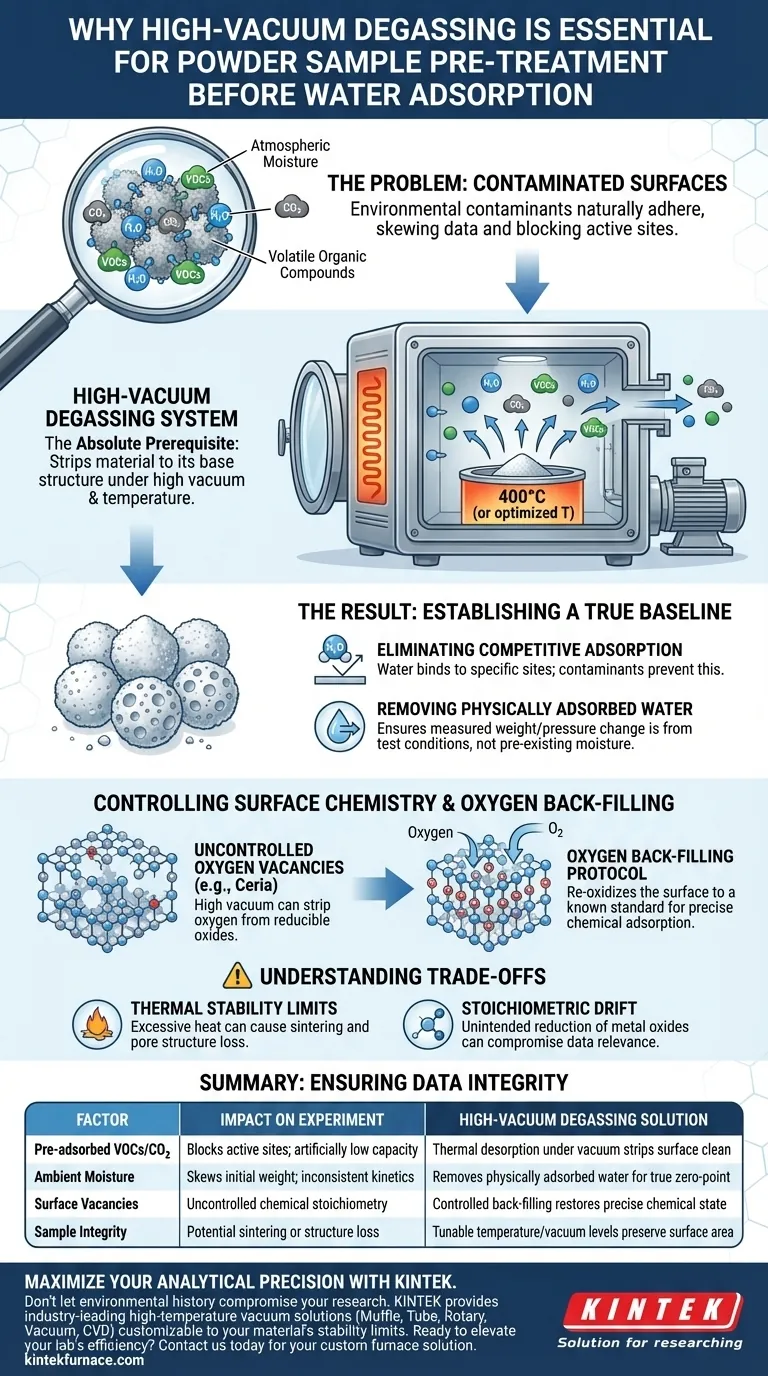

High-vacuum degassing is the absolute prerequisite for ensuring the validity of water adsorption data. This process removes environmental contaminants—specifically pre-adsorbed carbon dioxide, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and atmospheric moisture—that naturally adhere to powder surfaces. By subjecting the sample to high vacuum, typically at elevated temperatures around 400°C, you effectively strip the material down to its base chemical structure.

A successful experiment requires a known starting point. High-vacuum degassing provides a clean, well-defined initial surface state, ensuring that your data measures the material's intrinsic properties rather than its environmental history.

Establishing a True Baseline

The primary function of high-vacuum degassing is to "reset" the sample. Without this step, your results will be skewed by the invisible layer of contamination that exists on almost all powders exposed to air.

Eliminating Competitive Adsorption

Water adsorption experiments measure how water molecules interact with specific sites on your material's surface.

If these sites are already occupied by CO2 or VOCs, the water cannot bind to them. This leads to artificially low adsorption capacity readings and incorrect kinetic data.

Removing Physically Adsorbed Water

Powders are hygroscopic and naturally hold onto ambient moisture.

Degassing removes this "physically adsorbed" water. This ensures that any weight change or pressure drop measured during your experiment is due to the test conditions, not the release of pre-existing moisture.

Controlling Surface Chemistry

Beyond simple cleaning, advanced degassing protocols allow you to strictly control the chemical stoichiometry of the surface. This is vital for materials where surface defects play a role in reactivity.

The Importance of Oxygen Back-filling

For reducible oxides, such as cerium dioxide, high temperature and vacuum can alter the material's oxygen balance.

While the vacuum removes contaminants, it may also strip oxygen from the lattice, creating uncontrolled oxygen vacancies.

Creating a Well-Defined State

To counter this, a specific protocol involves back-filling the chamber with oxygen after the initial degassing.

This re-oxidizes the surface to a known standard. The result is a pristine, chemically accurate surface ready for precise chemical adsorption studies.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While essential, high-vacuum degassing is an aggressive process that must be tuned to your specific material.

Thermal Stability Limits

The standard 400°C treatment is effective for robust ceramics but can be destructive for sensitive materials.

Excessive heat can cause sintering, where particles fuse together. This drastically reduces surface area and alters the very pore structure you are trying to measure.

Stoichiometric Drift

As seen with cerium dioxide, vacuum environments can inadvertently reduce metal oxides.

If you fail to perform necessary restoration steps (like oxygen back-filling), you may be testing a material with a different defect density than intended, compromising the relevance of your data.

Ensuring Data Integrity in Your Experiments

To achieve reproducible results, your pre-treatment strategy must align with the chemical nature of your powder.

- If your primary focus is general capacity: Ensure your temperature is high enough to desorb water and VOCs, but low enough to prevent sintering.

- If your primary focus is surface chemistry (e.g., Ceria): Implement an oxygen back-fill step after degassing to standardize the oxygen vacancy concentration.

By rigorously defining your initial surface state, you transform your data from a rough estimate into a precise scientific measurement.

Summary Table:

| Factor | Impact on Experiment | High-Vacuum Degassing Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-adsorbed VOCs/CO2 | Blocks active sites; artificially low capacity | Thermal desorption under vacuum strips surface clean |

| Ambient Moisture | Skews initial weight; inconsistent kinetics | Removes physically adsorbed water for true zero-point |

| Surface Vacancies | Uncontrolled chemical stoichiometry | Controlled back-filling restores precise chemical state |

| Sample Integrity | Potential sintering or structure loss | Tunable temperature/vacuum levels preserve surface area |

Maximize Your Analytical Precision with KINTEK

Don't let environmental history compromise your research. KINTEK provides industry-leading high-temperature vacuum solutions designed to deliver the well-defined initial surface states your experiments demand.

Backed by expert R&D and manufacturing, we offer a full suite of Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum, and CVD systems, all fully customizable to your specific material stability limits and stoichiometry requirements. Whether you are treating sensitive reducible oxides or robust ceramics, our systems ensure your data reflects the material's intrinsic properties.

Ready to elevate your lab's efficiency? Contact us today to find your custom furnace solution.

Visual Guide

References

- Lee Shelly, Shmuel Hayun. Unveiling the factors determining water adsorption on CeO <sub>2</sub> , ThO <sub>2</sub> , UO <sub>2</sub> and their solid solutions. DOI: 10.1007/s12598-025-03393-w

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Furnace Knowledge Base .

Related Products

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace Molybdenum Wire Vacuum Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering and Brazing Furnace

People Also Ask

- What options are available for the vacuum furnace system? Customize for Precision and Performance

- Why is a high-vacuum environment necessary for gold electrode deposition? Key to Solar Cell Efficiency

- How does a vacuum pumping system contribute to the fabrication of high-quality silicide structures? Ensure Material Purity

- What critical tasks does a vacuum drying oven perform for WPU films? Ensure Defect-Free Composite Material Integrity

- How are high-temperature vacuum furnaces utilized in scientific research? Unlock Pure, Controlled Material Synthesis

- Why use a vacuum drying oven for mesoporous silica? Protect High Surface Area and Structural Integrity

- What are the key thermal properties of graphite for vacuum furnaces? Unlock High-Temperature Stability and Efficiency

- What is vacuum brazing used for? Achieve Clean, Strong, and Distortion-Free Joints