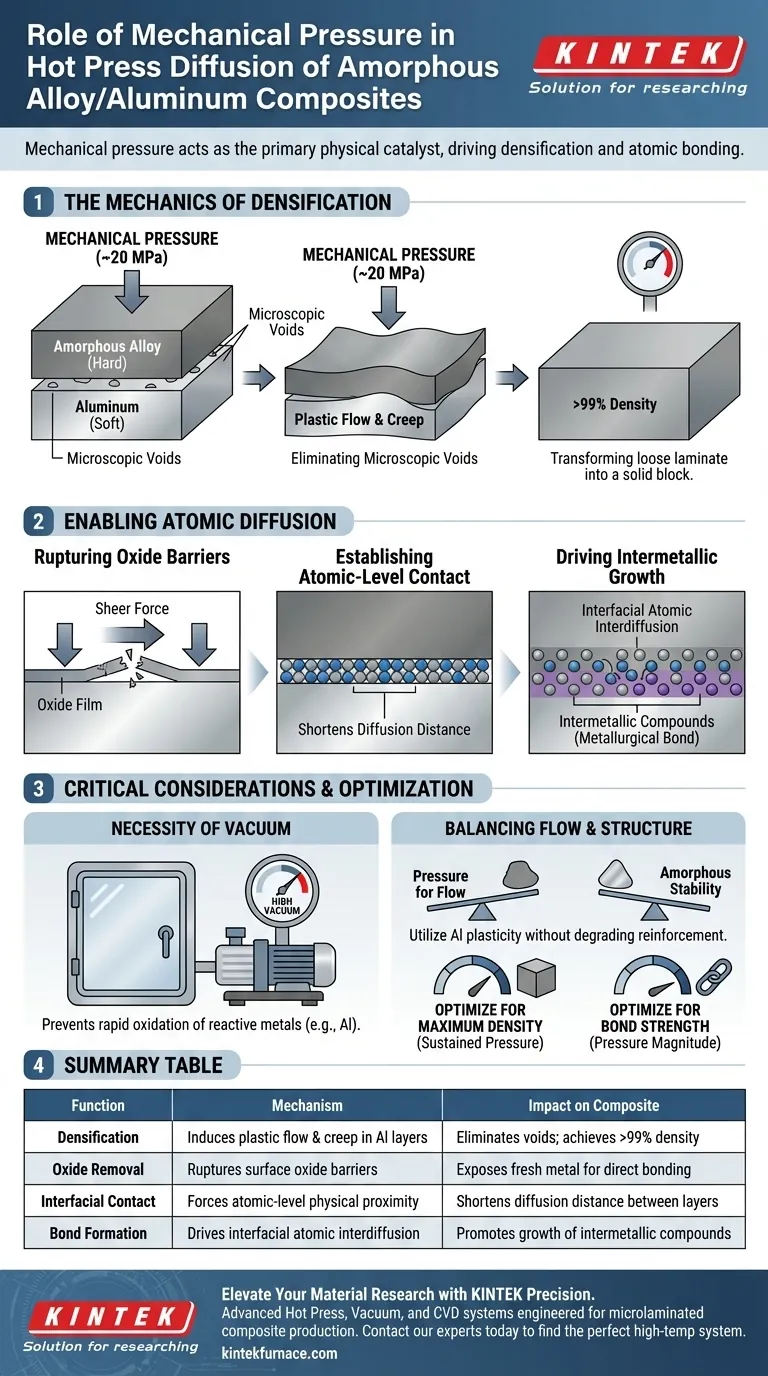

Mechanical pressure acts as the primary physical catalyst for bonding amorphous alloy/aluminum microlaminated composites. By applying continuous force, typically around 20 MPa, you compel the softer aluminum layers to undergo significant plastic deformation and creep. This mechanism fills microscopic voids and ensures the necessary atomic-level contact required for successful diffusion bonding.

Core Takeaway Mechanical pressure does not merely hold layers together; it actively drives the material transition from a stacked structure to a unified composite. It creates densification by forcing soft aluminum into gaps and rupturing surface oxides, creating the intimate contact required for atomic interdiffusion and intermetallic growth.

The Mechanics of Densification

Inducing Plastic Flow

The primary role of mechanical pressure is to exploit the mechanical differences between the layers. The aluminum layers are significantly softer than the amorphous alloy ribbons.

Under continuous pressure (e.g., 20 MPa), the aluminum undergoes plastic flow and creep. This forces the aluminum to deform and adapt to the surface topography of the harder amorphous alloy.

Eliminating Microscopic Voids

As the aluminum deforms, it flows into and fills the microscopic voids inherent in the stacked structure.

This process is critical for achieving high material density, often exceeding 99%. By eliminating these gaps, the pressure transforms a loose laminate into a solid, fully dense block.

Enabling Atomic Diffusion

Establishing Atomic-Level Contact

Diffusion cannot occur across a physical gap. Mechanical pressure forces the layers into atomic-level physical contact.

This close contact significantly shortens the distance required for atoms to travel between layers, acting as a prerequisite for any chemical bonding to occur.

Rupturing Oxide Barriers

Aluminum creates a natural, distinct oxide film on its surface that inhibits bonding.

The sheer force applied during the hot press process helps rupture this oxide film. Breaking this barrier increases the direct physical contact area between the metal matrix and the reinforcement, exposing fresh metal surfaces for bonding.

Driving Intermetallic Growth

Once the physical barriers are removed, pressure provides the driving force for interfacial atomic interdiffusion.

This exchange of atoms between the layers facilitates the nucleation and growth of intermetallic compounds, which creates the final metallurgical bond between the amorphous alloy and the aluminum.

Critical Considerations and Trade-offs

The Necessity of Vacuum

Pressure alone cannot guarantee a high-quality bond if the environment is reactive.

High-temperature processing creates a risk of rapid oxidation for reactive metals like aluminum. Therefore, mechanical pressure must be applied within a high vacuum environment to prevent the formation of new oxide inclusions that would weaken the interface.

Balancing Flow and Structure

While pressure drives densification, it relies on the aluminum being soft enough to flow.

If the pressure is insufficient, voids remain, leading to structural weakness. Conversely, the process relies on the amorphous alloy remaining stable; the pressure utilizes the aluminum's plasticity without degrading the amorphous nature of the reinforcement layers.

Optimizing the Hot Press Process

To achieve specific mechanical properties in your composite, consider how you manipulate the pressure variable:

- If your primary focus is Maximum Density: Ensure the pressure is sustained long enough to allow the aluminum to creep fully into all interstitial voids.

- If your primary focus is Interfacial Bond Strength: Prioritize pressure magnitude to ensure the effective rupture of the aluminum oxide film, enabling direct metal-to-metal diffusion.

By controlling mechanical pressure, you actively dictate the structural integrity and chemical connectivity of the final microlaminated composite.

Summary Table:

| Function | Mechanism | Impact on Composite |

|---|---|---|

| Densification | Induces plastic flow & creep in Al layers | Eliminates voids; achieves >99% density |

| Oxide Removal | Ruptures surface oxide barriers | Exposes fresh metal for direct bonding |

| Interfacial Contact | Forces atomic-level physical proximity | Shortens diffusion distance between layers |

| Bond Formation | Drives interfacial atomic interdiffusion | Promotes growth of intermetallic compounds |

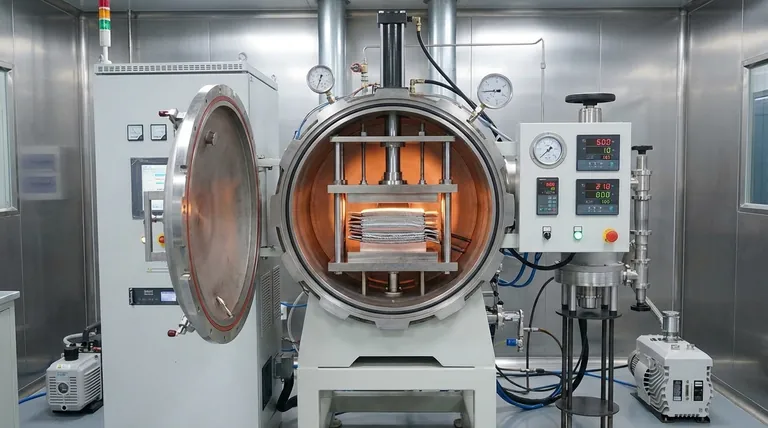

Elevate Your Material Research with KINTEK Precision

Unlock the full potential of your composite materials through superior thermal and mechanical control. Backed by expert R&D and world-class manufacturing, KINTEK provides advanced Hot Press, Vacuum, and CVD systems engineered for the rigorous demands of microlaminated composite production.

Whether you require customizable Muffle, Tube, or Rotary furnaces for specialized heat treatments, our lab solutions ensure the precise pressure and vacuum environments needed for high-density, defect-free bonding.

Ready to optimize your fabrication process? Contact our experts today to find the perfect high-temp system for your unique research needs.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What processes are used for vacuum pressing and preforming of fabrics and fiber materials? Master Uniform Consolidation for Composites

- How do hot press furnaces contribute to graphene synthesis? Unlock High-Quality Material Production

- What is the function of Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) coating on molds during vacuum hot press sintering? Protect Your Samples and Molds from Damage

- What is a vacuum hot press and what is its primary function? Unlock Advanced Materials Processing

- What is the maximum working temperature of a vacuum hot press furnace? Achieve Precise High-Temp Processing

- What roles do high-strength graphite molds play during the hot-pressing sintering of TiAl-SiC composites?

- How does a vacuum press machine work in shaping metals? Achieve Precision Metal Forming with Uniform Pressure

- What is the core role of a Vacuum Hot Pressing (VHP) furnace? Achieve Peak Infrared Transmittance in ZnS Ceramics