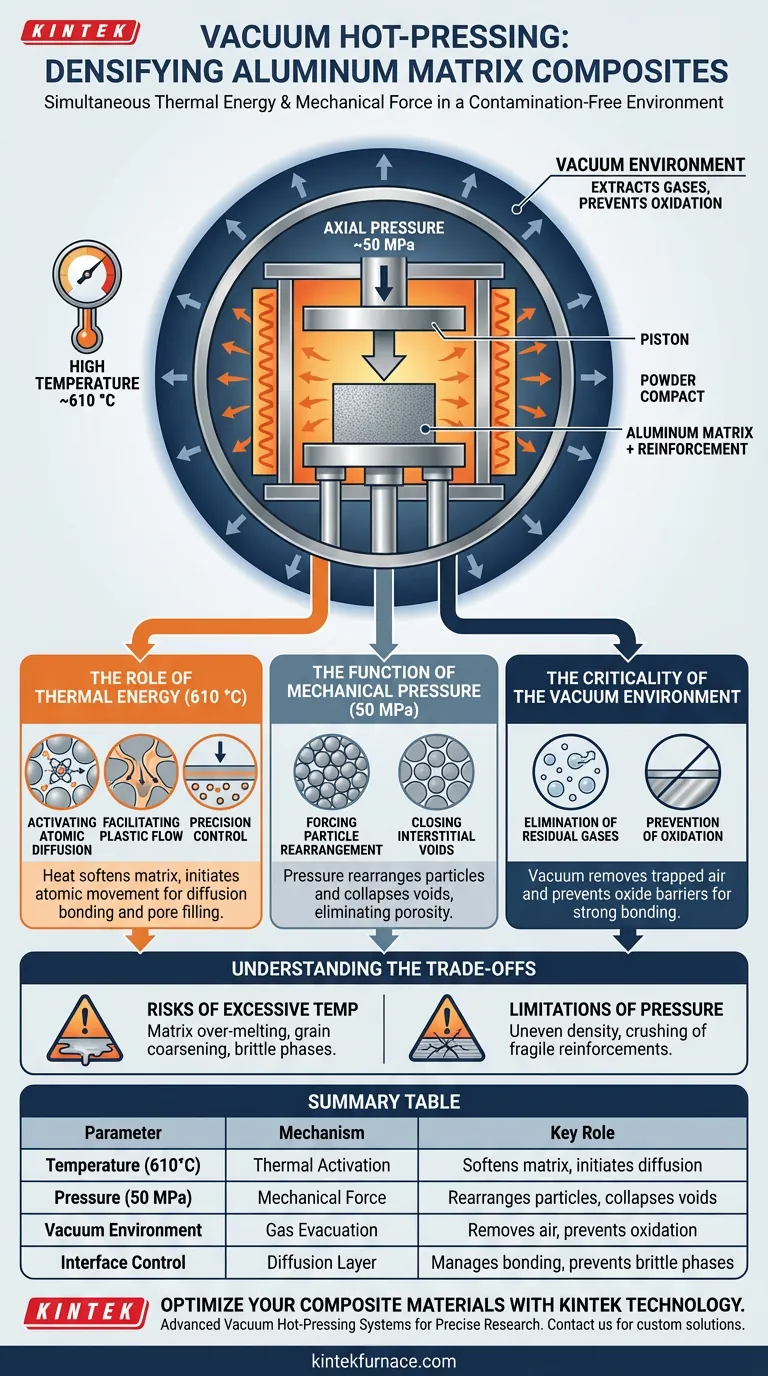

Vacuum hot-pressing mechanisms work by applying simultaneous thermal energy and mechanical force within a contamination-free environment to force material consolidation.

Specifically, a typical process utilizes a high-temperature environment around 610 °C combined with a constant axial pressure of approximately 50 MPa. These conditions induce plastic flow and atomic diffusion in the aluminum powder, while the vacuum extracts residual gases, allowing the material to bond and achieve near-theoretical density.

Core Takeaway Achieving high density in aluminum matrix composites requires overcoming the natural resistance of particles to bond due to oxide layers and pore-trapped gases. The vacuum hot-press solves this by physically forcing particle contact while thermally activating atomic movement in an environment that actively removes barriers to bonding.

The Role of Thermal Energy

The application of heat is the primary driver for changing the material's state from a loose powder to a cohesive solid.

Activating Atomic Diffusion

At temperatures such as 610 °C, the aluminum matrix gains sufficient thermal energy to facilitate diffusion bonding.

Heat increases the kinetic energy of atoms, providing the driving force for them to migrate across particle boundaries. This movement is essential for creating a metallurgical bond between the aluminum and the reinforcement phase.

Facilitating Plastic Flow

High temperatures soften the aluminum matrix, allowing it to undergo plastic flow.

This softening enables the metal to deform easily under pressure, filling the microscopic voids between the harder reinforcement particles. This flow is critical for eliminating the initial porosity of the green compact (the compressed powder).

Precision Control and Phase Transformation

Precise temperature regulation creates a diffusion-type transition layer with moderate thickness.

This control facilitates the shift from mechanical interlocking to metallurgical bonding. It ensures the reaction is strong enough to bond the materials but controlled enough to prevent grain coarsening or the over-melting of the aluminum matrix.

The Function of Mechanical Pressure

While heat softens the material, mechanical pressure provides the physical force necessary to densify it.

Forcing Particle Rearrangement

An axial pressure, typically around 50 MPa, forces the physical rearrangement of particles.

This external force overcomes friction between particles, packing them tightly together. In systems where the matrix and reinforcement (like carbon nanotubes) exhibit non-wetting phenomena, this pressure is mandatory to force contact that would not occur naturally.

Closing Interstitial Voids

Pressure mechanically collapses the empty spaces (pores) remaining between the particles.

By compressing the softened matrix, the applied force squeezes out voids. This significantly reduces porosity defects, leading to a final bulk material that is essentially free of internal gaps.

The Criticality of the Vacuum Environment

The vacuum is not merely an absence of air; it is an active processing tool that purifies the material during sintering.

Elimination of Residual Gases

The vacuum environment effectively evacuates gases trapped in the interstitial spaces between powder particles.

If these gases were not removed, they would be trapped inside the final product as pores, weakening the composite. The vacuum also removes volatiles released during the heating process.

Prevention of Oxidation

A high vacuum prevents the oxidation of the aluminum matrix, which is highly reactive at elevated temperatures.

Aluminum naturally forms a tough oxide film that hinders heat transfer and diffusion. By maintaining an oxygen-free environment, the furnace ensures a high-quality interface between the matrix and reinforcements (such as diamond or boron carbide), thereby enhancing thermal conductivity and bonding strength.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While vacuum hot-pressing is effective, the balance of conditions must be exact to avoid material degradation.

Risks of Excessive Temperature

If the temperature exceeds the optimal range (e.g., significantly above 610 °C), you risk matrix over-melting or grain coarsening.

This can degrade the mechanical properties of the composite. Additionally, excessive heat can cause aggressive interface reactions that create brittle phases, weakening the composite rather than strengthening it.

Limitations of Pressure Application

While pressure aids densification, it must be uniform.

Uneven pressure distribution can lead to density gradients within the part, where some areas are fully dense and others remain porous. Furthermore, excessive pressure on fragile reinforcements (like hollow spheres or specific ceramic structures) could crush them before the matrix flows around them.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To maximize the potential of aluminum matrix composites, align your furnace parameters with your specific material objectives:

- If your primary focus is maximum density: Prioritize maintaining high axial pressure (e.g., 50 MPa) to mechanically force the softened matrix into all interstitial voids.

- If your primary focus is thermal conductivity: Prioritize a high-quality vacuum and precise temperature control to prevent oxide formation and ensure a clean, conductive interface between the matrix and reinforcement.

- If your primary focus is mechanical strength: Focus on temperature regulation to promote diffusion bonding without causing grain coarsening or brittle reaction phases.

Success in vacuum hot-pressing lies in the precise synchronization of heat to soften, pressure to compress, and vacuum to purify.

Summary Table:

| Parameter | Mechanism | Key Role in Densification |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (610°C) | Thermal Activation | Softens matrix for plastic flow and initiates atomic diffusion bonding. |

| Pressure (50 MPa) | Mechanical Force | Rearranges particles and collapses interstitial voids to eliminate porosity. |

| Vacuum Environment | Gas Evacuation | Removes trapped air and prevents oxidation for clean metallurgical interfaces. |

| Interface Control | Diffusion Layer | Manages transition layer thickness to prevent brittle phases and grain coarsening. |

Optimize Your Composite Materials with KINTEK Technology

Precision is non-negotiable when sintering high-performance aluminum matrix composites. KINTEK provides industry-leading Vacuum Hot-Pressing systems, Muffle, Tube, and CVD furnaces designed to deliver the exact thermal and mechanical synchronization your research demands.

Why choose KINTEK?

- Advanced R&D: Systems engineered for precise temperature and pressure regulation.

- Total Customization: Tailor vacuum levels and heating cycles to your specific material needs.

- Expert Support: Leverage our manufacturing expertise to eliminate grain coarsening and porosity defects.

Ready to achieve near-theoretical density in your lab? Contact KINTEK today to discuss your custom furnace solution!

Visual Guide

References

- Yuan Li, Changsheng Lou. Improving mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of Al-Cu-Mg matrix composites by GNPs and sc additions. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-86744-y

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Furnace Knowledge Base .

Related Products

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 9MPa Air Pressure Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the primary functions of high-strength graphite molds? Optimize GNPs-Cu/Ti6Al4V Hot-Pressing Sintering

- What is the significance of the rapid heating capability of a hot press furnace? Unlock Nanoscale Sintering Precision

- What is vacuum hot pressing (VHP) and what materials is it suitable for? Unlock High-Density Material Solutions

- What are the advantages of using a Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) system? Unlock High-Entropy Alloy Performance

- Why is a high-vacuum environment required within a hot press for metallic glass? Ensuring Purity and Density

- What are the advantages of using hot deep drawing equipment for TC4 alloy? Achieve Smooth, Wrinkle-Free Parts

- What role does a vacuum hot pressing furnace play in (Ti2AlC + Al2O3)p/TiAl fabrication? Achieve 100% Densification

- What are the advantages of using vacuum hot press furnaces over traditional furnaces? Achieve Superior Material Quality and Performance