The Allure of a Single Number

"How fast does it pump down?"

It's often the first question asked when evaluating a vacuum furnace. And it's a fair one. We are psychologically wired to seek simple metrics. We want one number to tell us if something is "good" or "fast."

You might be told: 7 minutes to 0.1 Torr. Or, with an upgrade, 4.5 minutes to a deeper 10 microns.

These numbers are true, but they aren't the whole truth. They are the final scene of a complex play. To understand the real speed of your process, you have to understand the entire performance, not just the last line.

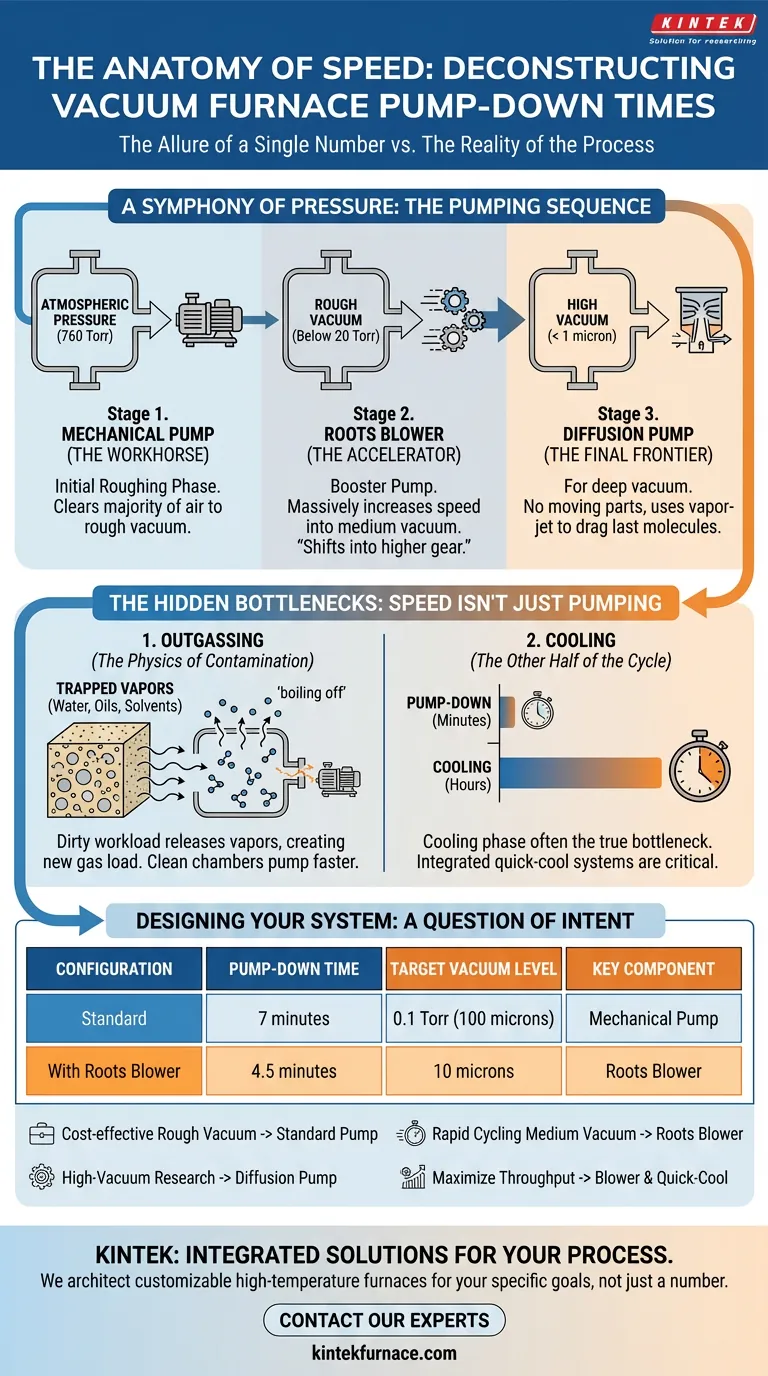

A Symphony of Pressure: The Pumping Sequence

A modern vacuum system isn't one pump. It’s a team of specialists, each designed to perform optimally in a specific pressure range, handing off the task to the next in a seamless sequence.

H3: The Workhorse: The Mechanical Pump

The process begins at atmospheric pressure (760 Torr). The first stage belongs to the workhorse: a mechanical pump. Its job is brute force—to remove the vast majority of air molecules from the chamber. This initial "roughing" phase clears the way, taking the chamber down into the rough vacuum range.

H3: The Accelerator: The Roots Blower

This is where the headline performance gain happens. A Roots blower isn't a replacement for the mechanical pump; it's a booster. It doesn't even turn on until the mechanical pump has thinned the air enough (e.g., below 20 Torr).

Once active, its high-speed impellers move a massive volume of the remaining low-pressure gas. It acts as an accelerator, rapidly pulling the chamber from a rough vacuum into the medium vacuum range. This is the component responsible for the dramatic leap in speed and depth—like shifting into a higher gear.

H3: The Final Frontier: The Diffusion Pump

For applications demanding true high vacuum—pressures below 1 micron—neither of the previous pumps will suffice. Here, a diffusion pump takes over. With no moving parts, it uses a vapor-jet principle to drag the last remaining molecules out. It’s a feat of elegant physics, enabling processes at the cutting edge of material science.

The Hidden Bottlenecks: Why Speed Isn't Just About Pumping

A fast pump-down time is satisfying. But total process time—the time from loading a part to unloading it—is what truly matters. And two invisible factors often have a greater impact than the pumps themselves.

H3: The Physics of Contamination: The Outgassing Problem

You can have the most powerful pumps in the world, but if your workload is "dirty," your pump-down time will suffer.

Outgassing is the slow release of trapped vapors—water, oils, solvents—from the surfaces of the materials inside your chamber. As the pressure drops, these molecules "boil" off, creating a new gas load that the pumps must constantly fight. A clean, empty chamber will always pump down faster than one with a porous, unprepared workload. Often, the bottleneck isn't the pump; it's the physics of the material itself.

H3: The Other Half of the Cycle: The Importance of Cooling

We fixate on the journey down to vacuum, but often, the journey back to atmospheric pressure takes even longer. For processes like vacuum heat treating, the cooling phase is the true bottleneck.

A system that pumps down in minutes is of little value if the part must then cool for hours. This is why integrated solutions like inert gas quick-cool systems are just as critical as the vacuum pumps. Optimizing for throughput means optimizing the entire cycle, not just one part of it.

Designing Your System: A Question of Intent

The ideal vacuum furnace configuration is not the one with the most powerful pumps. It's the one that perfectly matches your objective. The choice reflects a trade-off between speed, cost, and ultimate vacuum level.

| Configuration | Pump-Down Time | Target Vacuum Level | Key Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 7 minutes | 0.1 Torr (100 microns) | Mechanical Pump |

| With Roots Blower | 4.5 minutes | 10 microns | Roots Blower |

Making the right choice means defining your primary goal:

- For cost-effective rough vacuum: The standard mechanical pump is a robust and sufficient solution.

- For rapid cycling in the medium vacuum range: The Roots blower package is essential for speed and throughput.

- For high-vacuum research: A full system including a diffusion pump is necessary to reach the lowest pressures.

- For maximizing overall throughput: You must consider both the blower package for fast pump-down and quick-cool systems to minimize total cycle time.

Ultimately, a vacuum furnace is an integrated system. Building one correctly requires a deep understanding of the interplay between components. At KINTEK, we design and manufacture customizable high-temperature furnaces—from Muffle and Tube to advanced CVD systems—that are architected for your specific process. We ensure every component works in concert to achieve your true goal, not just a number on a spec sheet.

To build a system that matches your unique operational needs, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace Molybdenum Wire Vacuum Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

Related Articles

- The Pursuit of Nothing: How Vacuum Furnace Control Defines Material Destiny

- An Environment of Absence: The Strategic Power of Vacuum Furnaces

- The Physics of Flawless Production: Why Continuous Vacuum Furnaces Redefine Quality at Scale

- The Architecture of Purity: Deconstructing the Vacuum Furnace System

- Beyond the Heat: The Psychology of Perfect Vacuum Furnace Operation