The Paradox of the Perfect Void

A vacuum is a paradox.

It's the perfect environment for high-temperature heating. The near-total absence of molecules prevents oxidation and contamination, ensuring the absolute purity of the material being processed.

But this same emptiness becomes a fundamental weakness when the heating cycle ends. A vacuum is a superb thermal insulator. With no medium to carry heat away, a hot workload can only cool through thermal radiation—a slow, passive, and often frustratingly inefficient process.

This isn't just a physics problem. It's a production bottleneck.

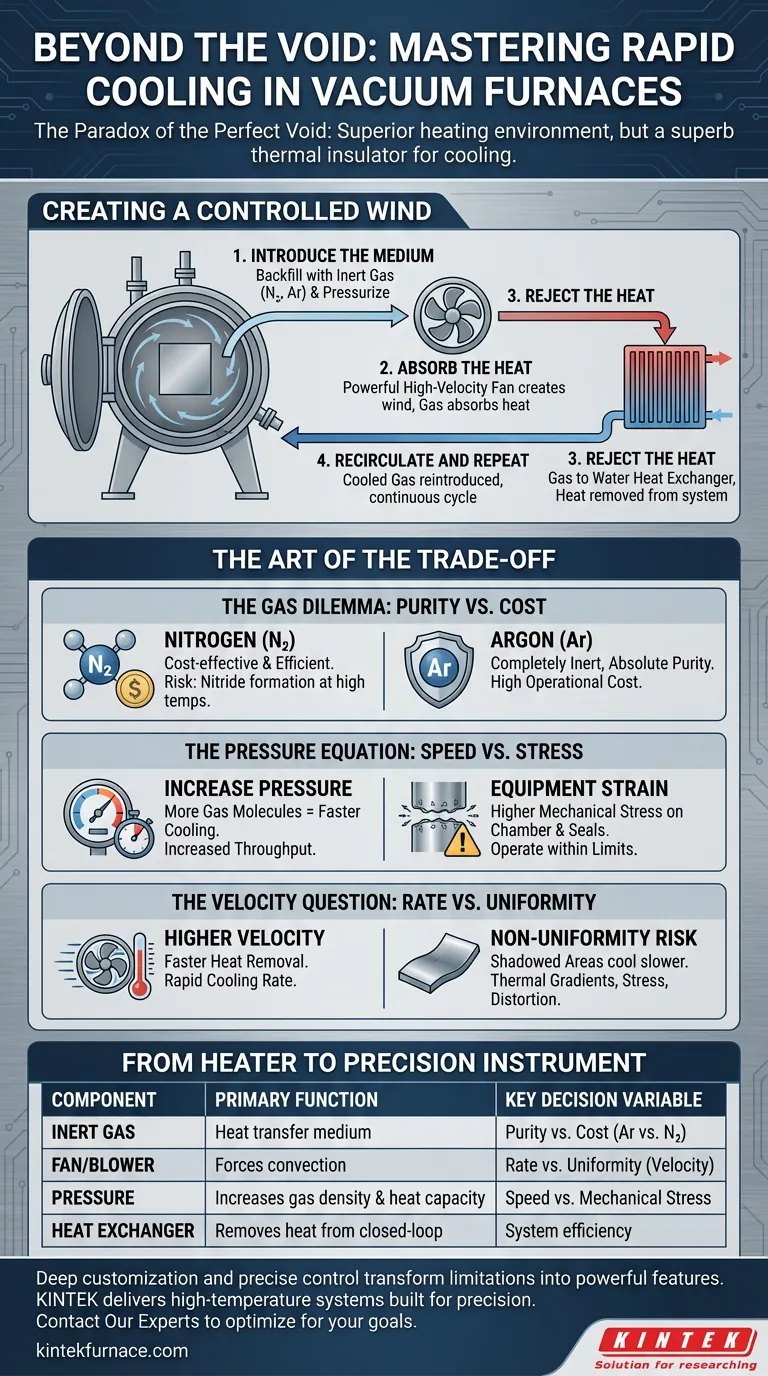

Creating a Controlled Wind

To overcome the insulating nature of the void, engineers devised an elegant solution: intentionally and precisely breaking the vacuum.

An inert gas circulation system doesn't just cool a part; it fundamentally changes the rules of thermal dynamics inside the furnace. It transforms cooling from a passive waiting game into an active, controlled process of forced convection.

The system works in a continuous, closed loop:

- Introduce the Medium: Once heating is complete, the chamber is backfilled with a high-purity inert gas, like Nitrogen or Argon. To maximize efficiency, the chamber is often pressurized, packing more heat-absorbing molecules into the space.

- Absorb the Heat: A powerful, high-velocity fan activates, creating a powerful "wind" that flows over the hot workload. The gas molecules absorb the thermal energy from the parts.

- Reject the Heat: The now-hot gas is ducted to an external gas-to-water heat exchanger. Here, the heat is transferred from the gas to the water, which carries it out of the system entirely.

- Recirculate and Repeat: The cooled, dense gas is then reintroduced to the fan to begin the cycle again, continuously pulling heat from the workload until a target temperature is reached.

The Art of the Trade-Off

Mastering this system is about more than just flipping a switch. It's a delicate balance of competing variables—a series of conscious decisions that directly shape your metallurgical outcome and production speed.

H3: The Gas Dilemma: Purity vs. Cost

The choice of gas is your first critical decision.

- Nitrogen is the workhorse. It's cost-effective and highly efficient. However, at extreme temperatures, it can react with certain alloys like titanium or some stainless steels, forming undesirable nitrides on the surface.

- Argon is the purist. It is completely inert and will not react with any material. This absolute purity comes at a significantly higher operational cost.

Your choice is a direct trade-off between process economics and metallurgical perfection.

H3: The Pressure Equation: Speed vs. Stress

Increasing the backfill gas pressure is the most direct way to accelerate cooling. More pressure means more gas molecules, which means a greater capacity to carry heat.

But this speed comes at a price: increased mechanical stress on the furnace chamber and its seals. You gain throughput, but you must operate within the engineered safety limits of your equipment.

H3: The Velocity Question: Rate vs. Uniformity

A higher gas velocity, driven by the fan, removes heat faster. The risk, however, is non-uniform cooling.

Parts directly in the path of the gas nozzles will cool much faster than those in "shadowed" areas. This thermal gradient can introduce stress, distortion, or warping in sensitive components. The goal is not just fast cooling, but controlled cooling.

From Heater to Precision Instrument

These trade-offs reveal the truth about modern thermal processing: a vacuum furnace is no longer just a simple heater. It's a precision instrument.

The ability to successfully navigate these choices depends entirely on the quality and design of your furnace. A well-engineered system incorporates sophisticated baffles and nozzles to ensure uniform flow, a robust chamber built to handle high pressures, and precise controls to modulate gas velocity.

This is where deep customization becomes critical. The optimal cooling strategy for a dense stack of small parts is vastly different from that for a single, large, complex geometry. A one-size-fits-all furnace forces you to compromise. A system tailored to your specific needs, however, allows you to optimize for your primary goal—be it maximum throughput, absolute material purity, or dimensional stability.

| Component | Primary Function | Key Decision Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Inert Gas | Heat transfer medium | Purity vs. Cost (Ar vs. N₂) |

| Fan/Blower | Forces convection | Rate vs. Uniformity (Velocity) |

| Pressure | Increases gas density and heat capacity | Speed vs. Mechanical Stress |

| Heat Exchanger | Removes heat from the closed-loop system | System efficiency |

By understanding and controlling these variables, you transform a furnace's greatest limitation into its most powerful feature.

Advanced furnace solutions are designed from the ground up to provide this level of control. With expert R&D and in-house manufacturing, KINTEK delivers high-temperature systems—from Tube and Muffle furnaces to highly specialized Vacuum and CVD systems—that are built for precision. Our deep customization capabilities ensure your equipment is perfectly aligned with your material and process goals.

To turn your thermal challenges into a competitive advantage, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace RTP Heating Tubular Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering and Brazing Furnace

Related Articles

- The Art of Isolation: Mastering Material Properties with Tube Furnaces

- Why Your Tube Furnace Is Failing Your Experiments (And It’s Not the Temperature)

- Beyond Heat: The Unseen Power of Environmental Control in Tube Furnaces

- Why Your High-Temperature Furnace Fails: The Hidden Culprit Beyond the Cracked Tube

- A War Against Chaos: The Elegant Engineering of the Modern Tube Furnace