Imagine a materials scientist meticulously preparing a precursor for a novel semiconductor. Hours of work culminate in placing the sample into a tube furnace, programmed for a precise, multi-stage heating cycle. The next day, analysis reveals a failure. The crystal structure is flawed, not because of the chemistry, but because of a subtle temperature gradient—a few degrees of difference between the blazing center and the slightly cooler ends of the process tube.

This scenario is all too common. It reveals a fundamental truth: generating heat is simple, but commanding it is a profound engineering challenge. A furnace is not just a box that gets hot. It is a finely tuned instrument designed to create a pocket of perfect thermal order in a universe that defaults to chaos.

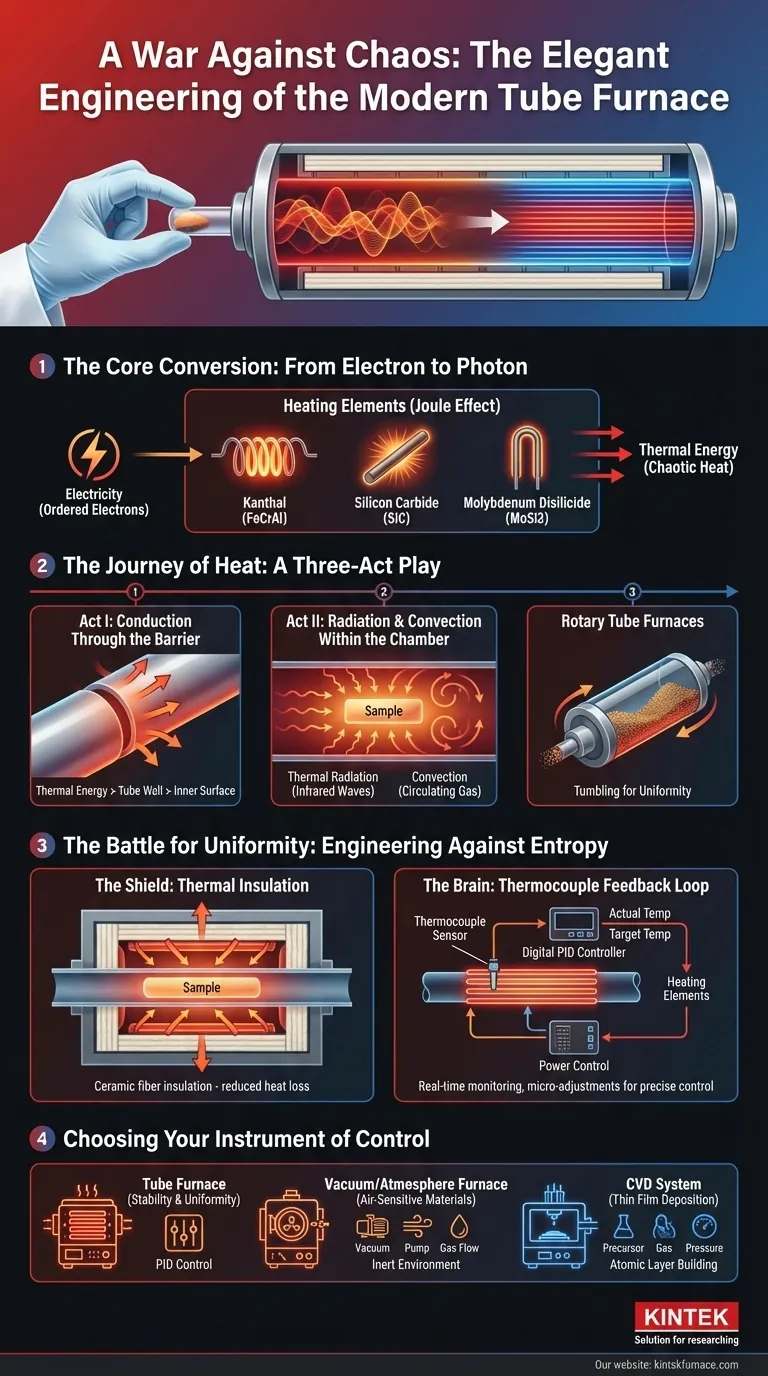

The Core Conversion: From Electron to Photon

At its heart, a modern laboratory furnace performs a simple, almost beautiful conversion of energy. It turns the orderly flow of electrons into the chaotic, powerful dance of thermal energy. This is primarily achieved through a principle discovered in the 1840s: the Joule effect.

The Workhorse: Resistance Heating

When electricity is passed through a material that resists its flow, that electrical energy has to go somewhere. It is released as heat. The heating elements in a furnace are the embodiment of this principle.

They are made not from excellent conductors, but from materials chosen for their stubbornness.

- Kanthal (FeCrAl) : A robust, reliable alloy for general-purpose heating.

- Silicon Carbide (SiC): For higher temperatures and rapid heating cycles.

- Molybdenum Disilicide (MoSi2): For the most extreme temperature demands, capable of operating in air without significant oxidation.

These elements, arranged around a central process tube, become incandescent, bathing the chamber in radiant thermal energy.

The Journey of Heat: A Three-Act Play

Creating heat is only the prologue. The critical story is how that heat reaches the sample uniformly and predictably. This journey happens in three distinct stages.

Act I: Conduction Through the Barrier

First, the thermal energy generated by the elements must cross the solid wall of the process tube. This occurs via conduction. The atoms in the tube material vibrate with energy, passing it from the outer surface to the inner wall. The choice of tube material—be it quartz, high-purity alumina, or a metal alloy—is the first point of control, dictating the maximum temperature and the speed of this transfer.

Act II: Radiation and Convection Within the Chamber

Once the inner wall is hot, it floods the internal volume with energy. Heat now travels to the sample through two mechanisms:

- Thermal Radiation: The hot wall emits infrared radiation, which travels directly to the sample. At high temperatures, this is the dominant mode of heat transfer.

- Convection: If an inert gas like argon or nitrogen is present, it heats up, circulates in currents, and gently transfers thermal energy to every surface of the sample.

For powdered or granular materials, ensuring every particle receives equal exposure can be a challenge. This is where systems like Rotary Tube Furnaces excel, by gently tumbling the material to guarantee uniform processing.

The Battle for Uniformity: Engineering Against Entropy

Heat, like all energy, seeks to dissipate. It naturally flows from hot to cold. The ends of a furnace tube, being closer to the outside world, are natural escape routes. This creates the temperature gradient that ruined our scientist's experiment.

The design of a high-performance furnace is, therefore, a strategic war against this natural tendency.

The Shield: Thermal Insulation

The first line of defense is containment. The entire heating assembly is encased in layers of high-grade ceramic fiber insulation. This material is mostly empty space, making it exceptionally difficult for heat to conduct or convect its way out. The insulation traps thermal energy, not just for energy efficiency, but to help create a stable, homogenous thermal environment.

The Brain: The Thermocouple Feedback Loop

The most critical component is the control system. A thermocouple—a sensor that translates temperature into a tiny voltage—is placed near the process tube. It acts as a vigilant scout, constantly reporting the real-time temperature back to a digital PID controller.

This controller performs a constant, high-speed comparison: Is the actual temperature the same as the target temperature? If it's too low, it sends more power to the heating elements. Too high, it throttles back. This feedback loop is a relentless conversation, making thousands of micro-adjustments to hold the temperature with astonishing precision.

Choosing Your Instrument of Control

Understanding this physics transforms how you select a furnace. The question is no longer "How hot can it get?" but "What kind of thermal environment do I need to create?"

- For Repeatable Synthesis & Annealing: The priority is stability and uniformity. A classic Tube Furnace with multi-zone heating and advanced PID control provides the most reliable environment.

- For Air-Sensitive Materials: The challenge is controlling both heat and atmosphere. A Vacuum or Atmosphere Furnace is essential, integrating precise heating with the ability to maintain a pure, inert environment.

- For Thin Film Deposition: The process requires a specialized evolution of the furnace. A CVD (Chemical Vapor Deposition) System is an integrated solution that manages heat, gas flow, and pressure to build materials one atomic layer at a time.

Ultimately, a furnace is an instrument for imposing order on matter. It leverages fundamental physics to create an environment where new materials and new discoveries can be forged. The quality of that instrument directly impacts the quality of the science. At KINTEK, we specialize in building these instruments of control, from versatile Muffle and Tube furnaces to highly customized CVD systems, ensuring your thermal environment is a variable you can master.

To achieve the precise control your research demands, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

- 1400℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz and Alumina Tube

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube

- Vertical Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

Related Articles

- Your Furnace Isn't Just a Heater: Why 'Good Enough' Equipment Is Sabotaging Your Advanced Materials Research

- Why Your High-Temperature Furnace Fails: The Hidden Culprit Beyond the Cracked Tube

- The Unsung Hero of the Lab: The Deliberate Design of the Single-Zone Split Tube Furnace

- The Art of Isolation: Mastering Material Properties with Tube Furnaces

- The Physics of Control: Mastering the Three-Stage Journey of Heat in a Tube Furnace