At its core, the vacuum inside a vacuum tube is necessary to create a clear, unobstructed path for electrons to travel. Without a vacuum, the air molecules inside the tube would collide with the electrons, scattering them and preventing the device from reliably controlling the flow of current. This makes the vacuum the fundamental enabler of the tube's function as an amplifier or switch.

The vacuum is not there to prevent all electrical current, as a simple insulator would. Instead, its purpose is to enable a controlled stream of electrons to flow predictably from one element to another, which is the basis of all vacuum tube operation.

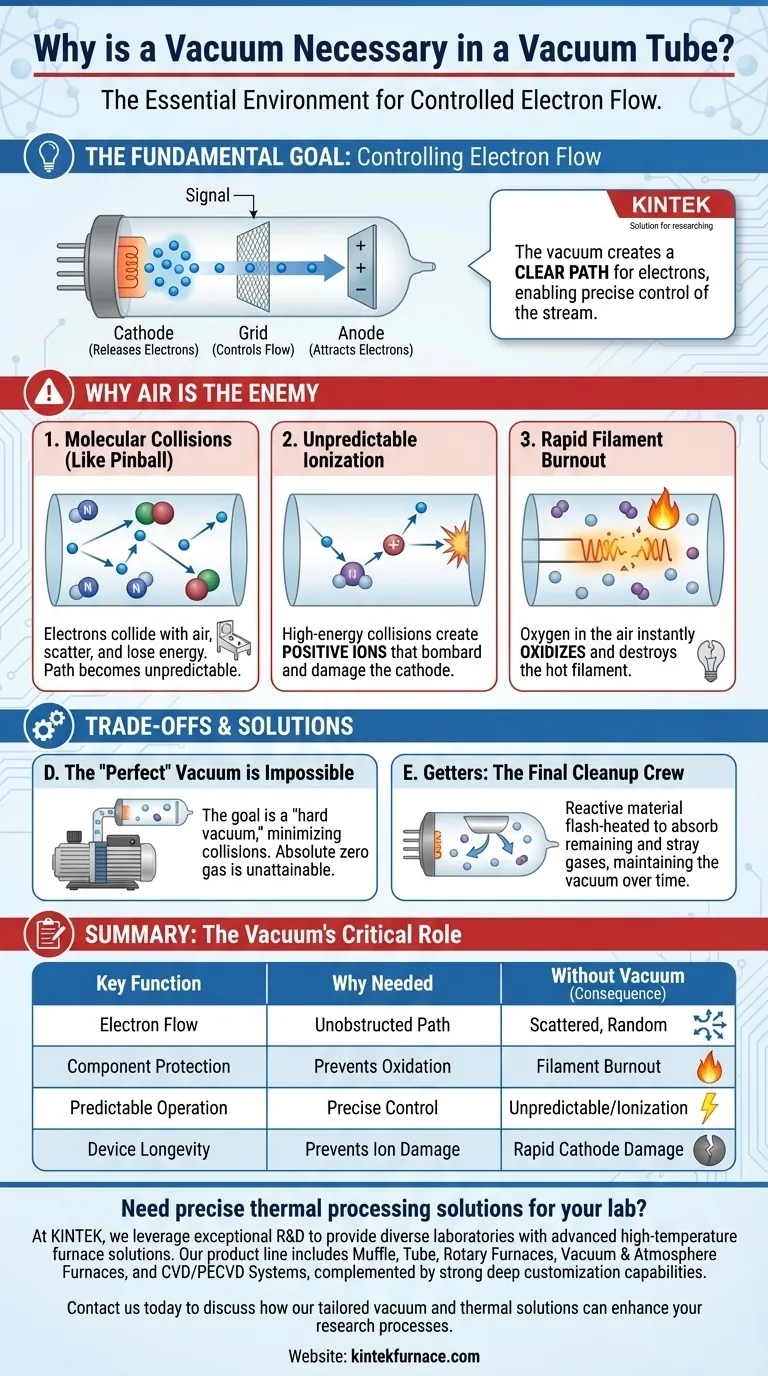

The Fundamental Goal: Controlling Electron Flow

To understand the need for a vacuum, we must first understand the basic job of a vacuum tube, also known as a valve. Its primary purpose is to take a small electrical signal and use it to control a much larger flow of electricity.

How a Vacuum Tube Works (The Basics)

A simple vacuum tube has three key parts working together. First, a cathode is heated until it releases a cloud of electrons, a process called thermionic emission.

Second, a distant plate called the anode (or plate) is given a strong positive charge, which attracts the negatively charged electrons from the cathode.

Finally, a mesh-like grid is placed between them. A small input signal applied to this grid can repel or allow electrons to pass through, effectively acting as a gate or valve that controls the primary electron stream.

Why Air is the Enemy of Controlled Current

If the tube were filled with air, this elegant process would fail completely. The seemingly empty space is, at a molecular level, a dense field of obstacles.

The Problem of Molecular Collisions

Think of the tube as a pinball machine. The electrons are the pinballs, and the anode is the target you want them to hit. In a vacuum, the path is clear.

If you fill the tube with air, it's like filling the pinball machine with millions of tiny, random bumpers. The electrons (pinballs) constantly collide with nitrogen and oxygen molecules, losing energy and scattering in random directions. Few, if any, would reach their intended target.

Unpredictable Behavior and Ionization

When an electron strikes a gas molecule with enough force, it can knock an electron off that molecule. This creates a positively charged ion.

These new, positively charged ions are then attracted to the negatively charged cathode. They accelerate toward it, bombarding its surface and causing physical damage that drastically shortens the tube's lifespan.

Rapid Filament Burnout

Most tubes use a tiny, hot wire called a filament to heat the cathode. In the presence of oxygen (a key component of air), this hot filament would oxidize and burn out almost instantly, exactly like the filament in a broken incandescent light bulb. The vacuum protects it.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Realities

Creating and maintaining this vacuum presents its own set of engineering challenges. It's a primary reason why vacuum tubes are complex and fragile compared to modern solid-state devices.

The Impossibility of a "Perfect" Vacuum

No vacuum is perfect. It's technologically impossible to remove every single gas molecule from an enclosure. The goal is to create a "hard vacuum" with so few molecules that collisions become statistically insignificant for the device's operation.

Getters: The Final Cleanup Crew

If you look inside a glass vacuum tube, you'll often see a shiny, silver or dark patch on the inside of the glass. This is the residue of a "getter."

After the tube is sealed, the getter material is flash-heated, causing it to bind with and absorb the vast majority of remaining gas molecules. It continues to absorb stray gases that may be released from the tube's metal components over its lifetime, helping maintain the vacuum.

Gas-Filled Tubes: The Exception to the Rule

While most tubes require a hard vacuum, some specialized tubes, like thyratrons or voltage regulators, are intentionally filled with a small amount of a specific, inert gas (like neon or argon). In these devices, the predictable ionization of the gas is used to achieve a specific switching behavior, but they are designed to handle the effects.

How to Apply This Knowledge

Understanding the vacuum's role is key to understanding the technology's strengths, weaknesses, and failure modes.

- If you are troubleshooting old audio or radio gear: A tube that has turned a milky white color has lost its vacuum. Air has leaked in, the getter is oxidized, and the tube is definitively dead.

- If you are studying electronics principles: Remember that the vacuum's purpose is to enable a free path for electron flow, making it fundamentally different from a simple insulator or a wire.

- If you are comparing technologies: The physical fragility, heat generation, and need for a sealed vacuum are the primary reasons why compact, durable, and efficient solid-state transistors ultimately replaced vacuum tubes in most applications.

Ultimately, the vacuum is not an empty, passive feature; it is the active, essential environment that allows a vacuum tube to perform its function.

Summary Table:

| Key Function | Why a Vacuum is Needed | Consequence Without Vacuum |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Flow | Creates unobstructed path for electrons | Electrons collide with air molecules, scattering randomly |

| Component Protection | Prevents oxidation and filament burnout | Hot filament burns out instantly in oxygen |

| Predictable Operation | Enables precise control via grid signal | Unpredictable behavior due to ionization and collisions |

| Device Longevity | Prevents ion bombardment damage to cathode | Rapid physical damage shortens tube lifespan |

Need precise thermal processing solutions for your lab?

At KINTEK, we leverage exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide diverse laboratories with advanced high-temperature furnace solutions. Our product line—including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems—is complemented by strong deep customization capabilities to precisely meet your unique experimental requirements.

Contact us today to discuss how our tailored vacuum and thermal solutions can enhance your research and development processes.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

- 1400℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz and Alumina Tube

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the key operational considerations when using a lab tube furnace? Master Temperature, Atmosphere & Safety

- How does a vertical tube furnace achieve precise temperature control? Unlock Superior Thermal Stability for Your Lab

- How is a high-temperature tube furnace utilized in the synthesis of MoO2/MWCNTs nanocomposites? Precision Guide

- What safety measures are essential when operating a lab tube furnace? A Guide to Preventing Accidents

- How is a Vertical Tube Furnace used for fuel dust ignition studies? Model Industrial Combustion with Precision