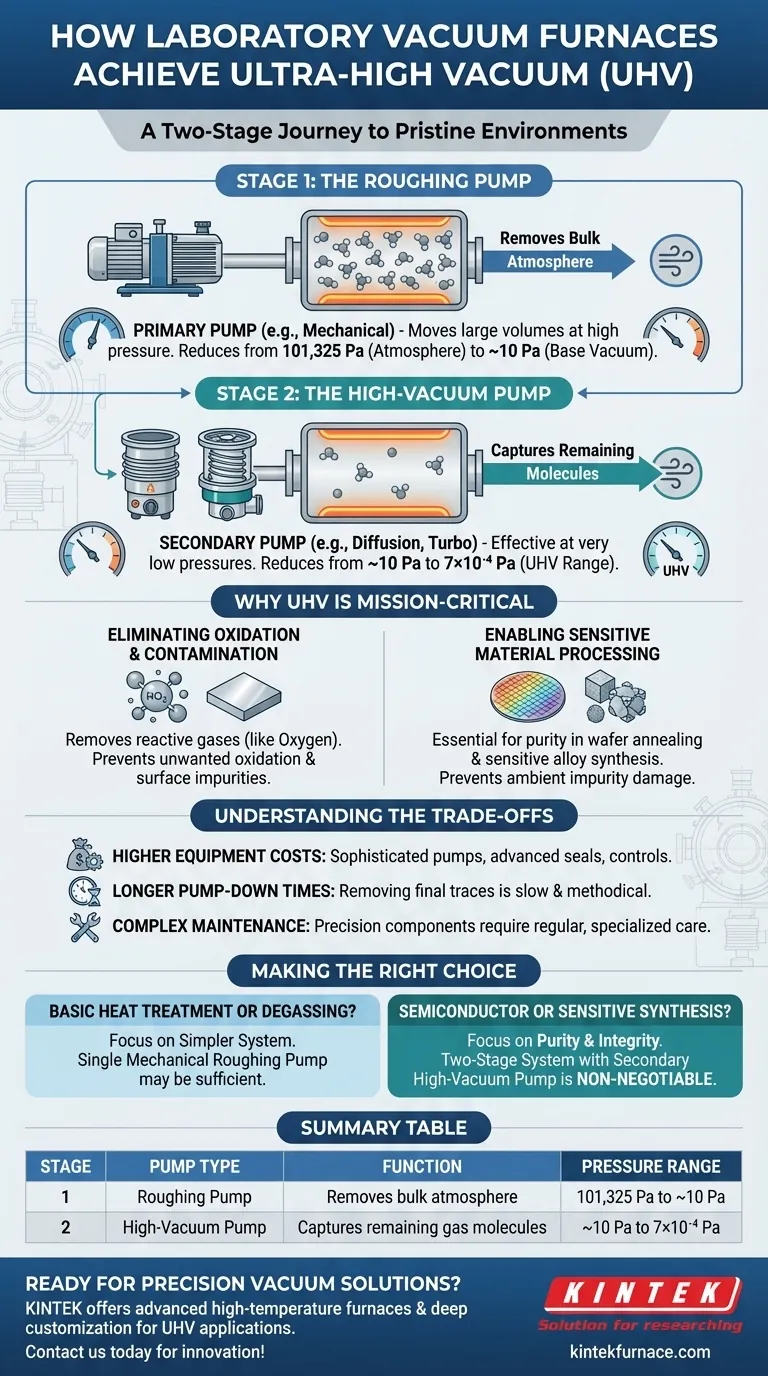

At its core, achieving ultra-high vacuum in a laboratory furnace is a two-stage process. The system first uses a mechanical "roughing" pump to remove the vast majority of air from the chamber. Once this initial vacuum is established, a secondary high-vacuum pump, such as a diffusion or molecular pump, takes over to capture the sparse remaining gas molecules and reach the required ultra-low pressures.

No single pump can efficiently operate across the vast pressure range from atmosphere to ultra-high vacuum. The solution is a necessary partnership: a primary pump to do the heavy lifting and a secondary pump for the highly specialized task of creating a near-perfect vacuum.

The Two-Stage Journey to Ultra-High Vacuum

Achieving an environment nearly devoid of particles is not a simple act of suction. It requires different technologies that are each optimized for a specific range of gas density.

Stage 1: The Roughing Pump

The first step is to remove the bulk of the atmosphere from the sealed furnace chamber. This is the job of a primary pump, often called a "roughing" pump.

These mechanical pumps are designed to move large volumes of gas at relatively high pressures. They bring the chamber down from atmospheric pressure to a base or "rough" vacuum level, typically around 10 Pa.

At this point, the pump's efficiency drops dramatically because there are too few gas molecules for its mechanical action to work effectively. It has created the necessary starting conditions for the next stage.

Stage 2: The High-Vacuum Pump

With the heavy lifting done, a secondary pump takes over. These pumps, such as diffusion or turbomolecular pumps, operate on principles that are effective at very low pressures.

A diffusion pump uses jets of hot oil vapor to "push" stray gas molecules toward an outlet, while a turbomolecular pump uses a series of high-speed rotating blades to strike molecules and direct them out of the chamber.

This secondary pump is what reduces the pressure from the rough vacuum level down to the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) range, as low as 7×10⁻⁴ Pa.

Why Ultra-High Vacuum is Mission-Critical

The significant effort and complexity required to achieve UHV are justified by the absolute need for a pristine processing environment.

Eliminating Oxidation and Contamination

At normal atmospheric pressure, reactive gases like oxygen are abundant and will instantly interact with a material's surface, especially at high temperatures.

A UHV environment effectively removes these reactive gases, preventing unwanted oxidation and surface contamination that could compromise the material's properties.

Enabling Sensitive Material Processing

For advanced applications, purity is paramount. Even a few foreign atoms can alter the performance of a final product.

Processes like semiconductor wafer annealing or the synthesis of highly sensitive alloys require UHV to ensure that the material's structural and electronic properties are not ruined by ambient impurities.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Realities

While powerful, UHV furnace technology comes with inherent complexities that must be managed. This capability is a trade-off between performance and operational cost.

Higher Equipment Costs

The inclusion of sophisticated secondary pumps, advanced controllers, and high-integrity seals makes UHV systems significantly more expensive than standard vacuum or atmosphere furnaces.

Longer Pump-Down Times

Reaching ultra-high vacuum is a process of diminishing returns. Removing the final traces of gas from the chamber and its internal surfaces is a slow, methodical process that can add significant time to each operational cycle.

Complex Maintenance

The pumps, valves, and seals that maintain UHV are precision components. They require specialized, regular maintenance to prevent leaks and ensure the system can consistently reach its target pressure.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The required vacuum level is dictated entirely by the sensitivity of your material and process.

- If your primary focus is basic heat treatment or degassing: A simpler and more cost-effective system using only a mechanical roughing pump may be sufficient.

- If your primary focus is semiconductor processing or sensitive material synthesis: A two-stage system with a secondary high-vacuum pump is non-negotiable to guarantee the purity and integrity of your results.

Understanding this staged approach empowers you to select the right equipment to ensure the success of your work.

Summary Table:

| Stage | Pump Type | Function | Pressure Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roughing Pump | Removes bulk atmosphere | From 101,325 Pa to ~10 Pa |

| 2 | High-Vacuum Pump | Captures remaining gas molecules | From ~10 Pa to 7×10⁻⁴ Pa |

Ready to elevate your lab's capabilities with precision vacuum solutions? At KINTEK, we leverage exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnace systems, including Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our deep customization ensures they meet your unique experimental needs for ultra-high vacuum applications. Contact us today to discuss how our solutions can enhance your material processing and drive innovation!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

- 1400℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in LP-DED? Optimize Alloy Integrity Today

- What are the general operational features of a vacuum furnace? Achieve Superior Material Purity & Precision

- What are the components of a vacuum furnace? Unlock the Secrets of High-Temperature Processing

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance

- What are the benefits of vacuum heat treatment? Achieve Superior Metallurgical Control