The Allure of a Single Number

When engineers specify equipment, we instinctively search for a single, defining metric. What's the maximum temperature? The chamber volume? The power rating? This bias for simplicity is a powerful cognitive shortcut.

But when it comes to a vacuum furnace, asking "What's the operating pressure?" is the right question with the wrong assumption. It assumes the answer is one number.

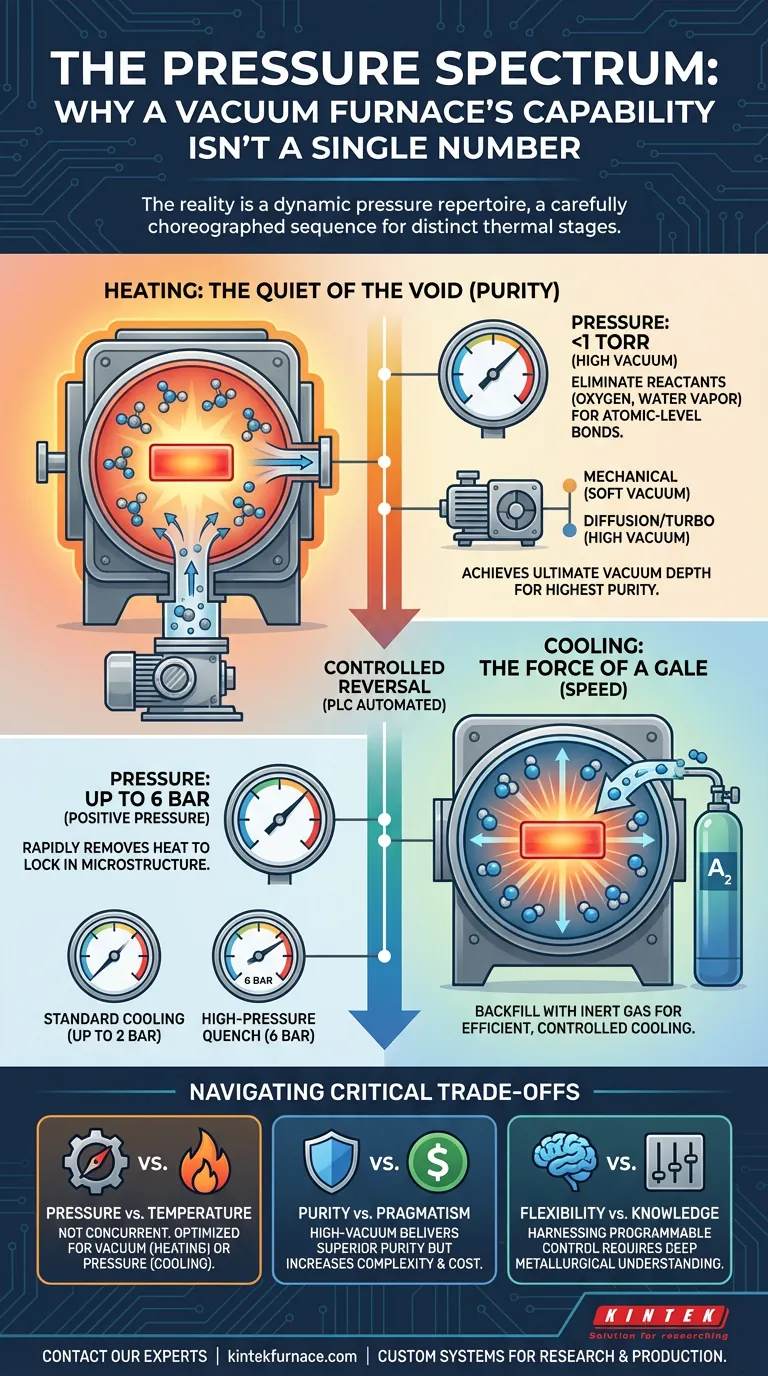

The reality is more elegant. A vacuum furnace doesn't have an operating pressure; it has a dynamic pressure repertoire, a carefully choreographed sequence of atmospheric conditions designed for distinct stages of a thermal process. Understanding this is the difference between acquiring a tool and mastering a process.

A Tale of Two Atmospheres: Heating vs. Cooling

The core of a furnace's function is a dramatic transition between two opposing goals: absolute purity during heating and controlled force during cooling. Each demands a completely different atmospheric strategy.

The Quiet of the Void: Pressure During Heating

During the critical heating and soaking phases, the furnace's primary role is to create a pristine canvas. At maximum temperature, its world shrinks to a near-perfect vacuum, operating from high-vacuum levels up to just 1 torr.

This isn't just about removing air. It's about eliminating the reactants—oxygen, water vapor, and other gases—that would otherwise corrupt the metallurgical process. For applications like brazing or sintering, where atomic-level bonds are being formed, this ultra-low pressure environment is non-negotiable. It ensures purity.

The Force of a Gale: Pressure During Quenching

Once the heating cycle is complete, the objective flips 180 degrees. The goal is no longer purity but speed—rapidly removing heat to lock in a desired material microstructure.

Here, the vacuum becomes a liability. The furnace executes a controlled reversal, backfilling the chamber with an inert gas like argon or nitrogen.

- Standard Cooling: A backfill of up to 2 bar of positive pressure provides efficient, rapid cooling.

- High-Pressure Quench: For maximum cooling rates to achieve specific hardness, an optional system can unleash a 6 bar torrent of gas, forcing heat away from the workpiece with incredible velocity.

This high-pressure phase is fundamentally a cooling tool, not a heating one.

The Choreography of Control

This versatility doesn't happen by accident. It's the result of a sophisticated interplay between a powerful pumping system and a precise gas control logic—the muscle and the brain of the furnace.

The Art of Evacuation

The ultimate vacuum level—the "depth" of the void—is determined by the pumping system. This is a critical design choice, driven entirely by process requirements.

- Mechanical Pumps: Achieve a "soft" vacuum, sufficient for basic degassing and many standard processes.

- Diffusion or Turbomolecular Pumps: Required for "high" vacuum, essential for applications demanding the highest levels of purity and the removal of all outgassing contaminants.

The Dialogue with Gas

The furnace's brain is its Programmable Logic Controller (PLC). It automates the transition between vacuum and pressure, managing partial pressure setpoints with inert gas. This system allows for incredibly complex and repeatable cycles, where the atmosphere is tailored second-by-second to the needs of the material.

The Engineer's Compass: Navigating Critical Trade-offs

This level of control introduces decision points. Choosing the right configuration requires moving past simple specs and engaging with the inherent trade-offs of the system.

-

Pressure vs. Temperature: The most crucial constraint to understand is that high positive pressure and maximum temperature are generally not concurrent. The system is optimized for vacuum during heating and pressure during cooling. Processes needing both simultaneously (like sinter-HIP) require a different class of furnace.

-

Purity vs. Pragmatism: A high-vacuum system delivers superior purity but comes with increased complexity and cost. The right choice depends on a frank assessment of your material's sensitivity to atmospheric contaminants.

-

Flexibility vs. Knowledge: A programmable controller offers near-infinite possibilities. But harnessing that power requires a deep understanding of the process metallurgy. The furnace is a powerful instrument, and its output is only as good as the composition it's asked to play.

Choosing a furnace, then, is less about finding the highest number on a spec sheet and more about matching the system's dynamic capabilities to your specific goals. At KINTEK, we build our vacuum furnaces—along with our Muffle, Tube, and CVD systems—on this principle of deep customization. We understand that whether your goal is absolute purity for brazing or controlled hardness for mechanical parts, the furnace must be a precise extension of your process intent.

To navigate these trade-offs and configure a system perfectly aligned with your research or production needs, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

Related Articles

- The Tyranny of Air: How Vacuum Furnaces Forge Perfection by Removing Everything

- The Most Important Number in a Vacuum Furnace Isn't Its Temperature

- The Pursuit of Nothing: How Vacuum Furnace Control Defines Material Destiny

- The Unseen Advantage: How Vacuum Furnaces Forge Metallurgical Perfection

- The Alchemy of the Void: How Vacuum Furnace Components Engineer Material Perfection