The Speed Fallacy

An engineer specifies a new heat treatment cycle. The goal is maximum hardness for a complex tool steel part. The first instinct, a deeply human one, is to cool it as fast as possible. We associate speed with strength, and a rapid quench seems like the most direct path to the desired result.

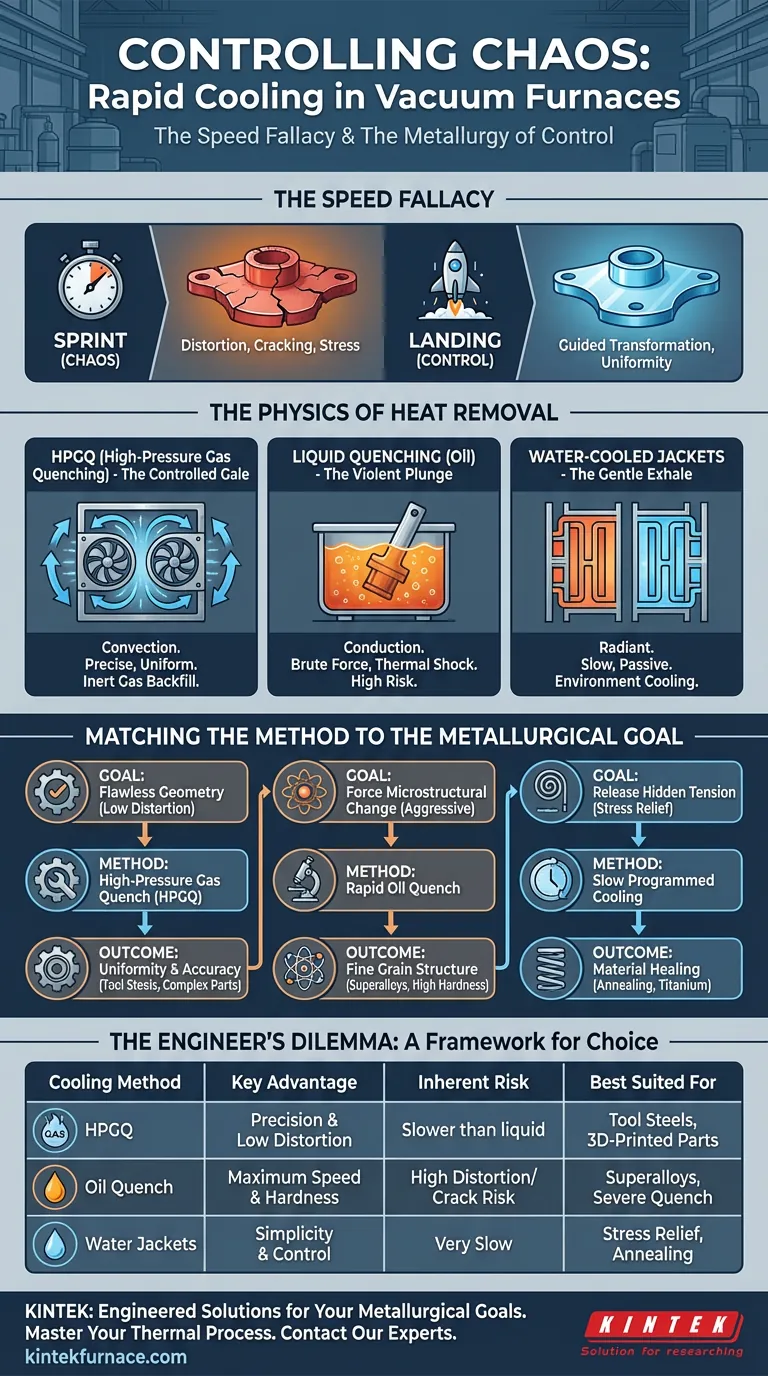

This is the speed fallacy.

In the world of metallurgy, the most critical factor isn't the absolute velocity of cooling, but the precise control over that velocity. The goal is not just to remove heat, but to guide the material through a specific metallurgical transformation, avoiding the chaos of distortion, cracking, and internal stress. It’s a process less like a sprint and more like landing a spacecraft.

The Physics of Heat Removal

To master the cooling process, we must first understand how heat actually leaves the workpiece. Each method leverages a different principle of thermal transfer, offering a unique balance of speed and control.

High-Pressure Gas Quenching (HPGQ): The Controlled Gale

This is the workhorse of modern vacuum furnaces. Imagine a hurricane, perfectly contained and directed within a sealed chamber.

After heating, the chamber is backfilled with a high-purity inert gas like nitrogen or argon. A powerful fan circulates this gas at high velocity, pressurizing it to two atmospheres or more. The gas absorbs heat directly from the part (convection), carries it to a water-cooled heat exchanger, and returns, chilled, to repeat the cycle. It is clean, precise, and remarkably uniform.

Liquid Quenching: The Violent Plunge

Liquid quenching is thermal shock by design. The heated part is submerged into a bath of specialized oil. The immense temperature difference and direct contact (conduction) facilitate a heat transfer rate that gas can never achieve.

This method is brute force. It's reserved for materials, like certain superalloys, that require a severe quench to lock in their properties before undesirable phases can form. The trade-off is a significantly higher risk of distortion and the need for post-process cleaning.

Water-Cooled Jackets: The Gentle Exhale

This method is part of the furnace's architecture. The chamber walls themselves are jacketed with channels where cooling water circulates.

Unlike direct quenching, this technique cools the entire environment by removing radiant heat. It’s a slow, passive, and gentle process. It offers the least speed but can be essential when the goal is to allow the material to relax, not shock it into a new state.

Matching the Method to the Metallurgical Goal

The right cooling technique is defined not by a stopwatch, but by the desired outcome at a microscopic level. The engineering goal dictates the method.

The Goal: Flawless Geometry and Uniform Strength

For complex tool and die geometries, the primary concern is preventing distortion. Even microscopic warping can render an expensive part useless.

- Method: High-Pressure Gas Quenching (HPGQ).

- Psychology: This is a risk-averse, precision-focused approach. The uniformity of gas flow minimizes thermal gradients across the part, ensuring it cools evenly and predictably. This is the path to achieving hardness without sacrificing dimensional accuracy.

The Goal: Forcing a Microstructural Change

For materials like nickel-based superalloys, the goal is aggressive intervention. You need to cool the material so quickly that its atomic structure doesn't have time to settle into a coarse or undesirable state.

- Method: Rapid Oil Quenching.

- Psychology: This approach accepts risk for a high reward. The severe thermal shock is a necessary evil to achieve a fine, refined grain structure, which is critical for the material’s performance at extreme temperatures.

The Goal: Releasing Hidden Tension

For processes like stress-relief annealing of titanium or 3D-printed components, the objective is the opposite of a quench. You need a slow, controlled cool-down to allow internal stresses to relax.

- Method: Programmed slow cooling with an inert gas backfill (often aided by water-cooled jackets).

- Psychology: This requires patience. Instead of forcing a change, you are creating the ideal conditions for the material to heal itself. Rushing this process would lock in the very stresses you are trying to remove.

The Engineer's Dilemma: A Framework for Choice

Every engineering decision is a series of trade-offs. Choosing a cooling method requires balancing the ideal metallurgical outcome against the practical risks.

| Cooling Method | Key Advantage | Inherent Risk | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Pressure Gas Quench | Precision & Low Distortion | Slower than liquid | Tool Steels, 3D-Printed Parts, Complex Geometries |

| Oil Quench | Maximum Speed & Hardness | High Distortion/Crack Risk | Superalloys, Materials Requiring Severe Quench |

| Water-Cooled Jackets | Simplicity & Control | Very Slow | Stress Relief, Annealing, Slow Cooling Cycles |

Ultimately, your decision is guided by your primary objective:

- For hardness with minimal distortion: Specify a system for high-pressure gas quenching.

- For aggressive phase transformation: Engineer for rapid oil quenching, and plan for the consequences.

- For stress relief and stability: Design for slow, programmed cooling in an inert environment.

From Abstract Physics to Tangible Results

Mastering thermal processing isn't just about reaching a target temperature; it's about controlling the entire journey, especially the critical descent back to ambient. This requires more than a furnace; it requires an engineered solution.

At KINTEK, we build systems—from Muffle and Tube Furnaces to advanced Vacuum and CVD systems—designed around your specific metallurgical goals. Our deep customization capability means we engineer the cooling system, whether it's a precisely controlled HPGQ setup or a robust oil quench tank, to give you the control you need to produce repeatable, reliable results.

If you're ready to move beyond the speed fallacy and master your thermal process, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

Related Articles

- More Than a Void: The Inherent Energy Efficiency of Vacuum Furnace Design

- The Physics of Perfection: How a Vacuum Furnace Creates Order from Chaos

- The Unseen Architect: How Vacuum Furnaces Forge the Future of Composites

- From Brute Force to Perfect Control: The Physics and Psychology of Vacuum Furnaces

- The Unseen Enemy: How Vacuum Furnaces Redefine Material Perfection