Technically speaking, almost every metal can be heated by induction, but the efficiency varies dramatically. The question is not which metals cannot be heated, but rather which are challenging and inefficient to heat. The primary factors determining a metal's suitability for induction heating are its magnetic permeability and its electrical resistivity.

The core principle to understand is this: Induction heating relies on two phenomena—magnetic hysteresis and electrical resistance. Metals that are magnetic and have high electrical resistance (like carbon steel) heat exceptionally well. Metals that lack one or both of these properties (like aluminum or copper) can still be heated, but it requires more power and specialized equipment.

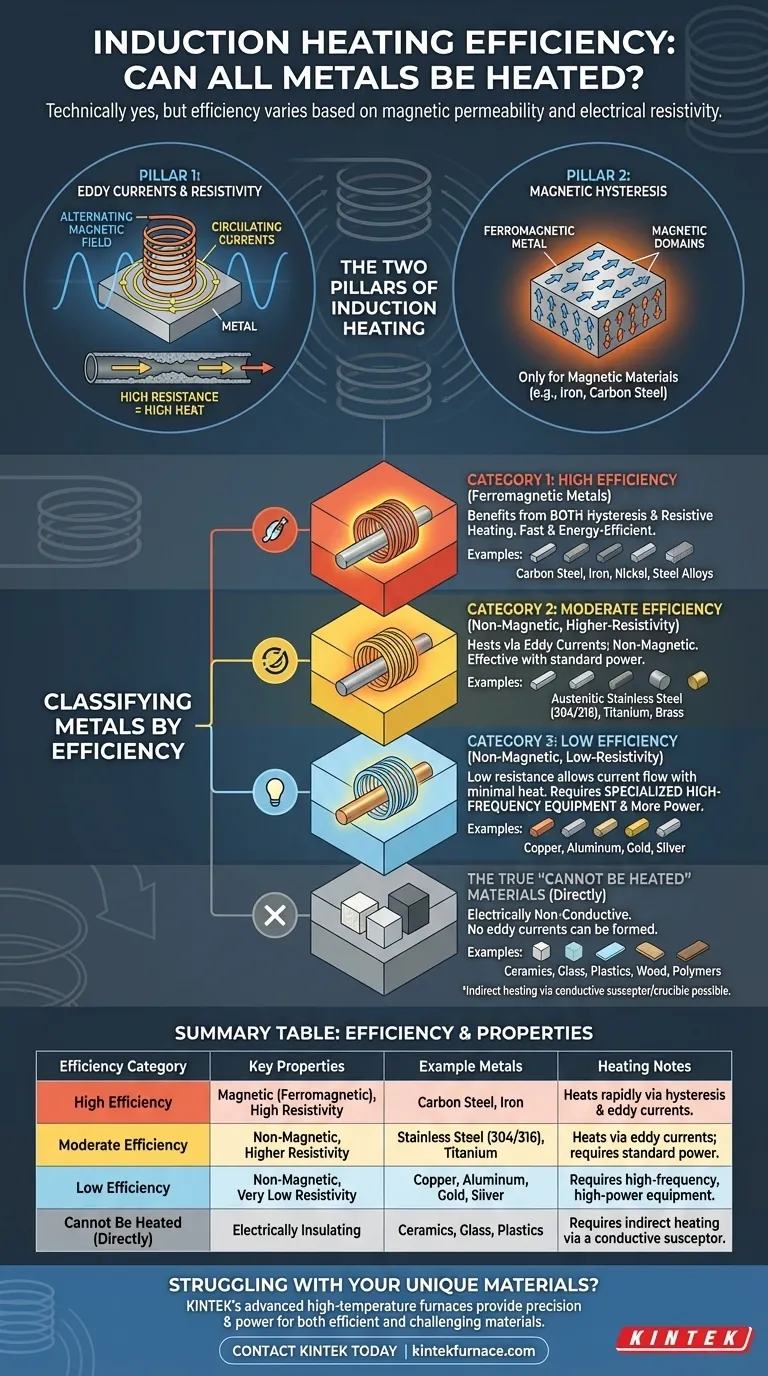

The Two Pillars of Induction Heating

To understand why some metals are harder to heat than others, you must first understand the two physical principles at work.

Pillar 1: Eddy Currents and Electrical Resistivity

An induction coil generates a powerful, rapidly alternating magnetic field. When a conductive material like a metal is placed inside this field, it induces electrical currents within the metal. These looping currents are called eddy currents.

As these eddy currents swirl through the material, they encounter electrical resistance. This resistance converts the electrical energy into heat, a phenomenon known as Joule heating.

Think of it like water flowing through pipes. A high-resistance material is like a narrow, rough pipe that creates a lot of friction (heat) for the water (current) passing through it. A low-resistance material is like a wide, smooth pipe where water flows easily with very little friction.

Pillar 2: Magnetic Hysteresis

This second effect only applies to magnetic materials, such as iron and carbon steel. These materials are composed of tiny magnetic regions called domains.

When exposed to the alternating magnetic field of the induction coil, these magnetic domains rapidly flip back and forth, trying to align with the field. This rapid internal friction generates a significant amount of heat.

This "bonus" heat from hysteresis is what makes ferromagnetic metals so incredibly easy and efficient to heat with induction. This effect ceases once the metal is heated past its Curie temperature, at which point it loses its magnetic properties.

Classifying Metals by Induction Efficiency

Based on these two principles, we can group metals into three distinct categories of heating efficiency.

Category 1: High Efficiency (Ferromagnetic Metals)

These are the ideal candidates for induction heating. They benefit from both hysteresis losses and resistive heating, making the process fast and energy-efficient.

- Examples: Carbon steel, iron, nickel, and many steel alloys.

Category 2: Moderate Efficiency (Non-Magnetic, Higher-Resistivity Metals)

These metals are not magnetic, so they do not benefit from hysteresis heating. However, they have relatively high electrical resistance, so the eddy currents generated within them still produce heat effectively.

- Examples: Austenitic stainless steels (like 304 and 316), titanium, and brass.

Category 3: Low Efficiency (Non-Magnetic, Low-Resistivity Metals)

These metals are the most challenging. They are not magnetic, and their very low electrical resistance allows eddy currents to flow with little opposition, generating minimal heat.

Heating these materials is possible but requires specialized induction equipment that uses a higher frequency. Higher frequencies force the eddy currents into a smaller area near the surface (the "skin effect"), concentrating the heating effect. This process requires significantly more power than heating steel.

- Examples: Copper, aluminum, gold, silver.

The True "Cannot Be Heated" Materials

While almost any metal can be heated with the right equipment, there is a class of materials that cannot be heated directly by induction at all.

Electrically Non-Conductive Materials

Induction heating fundamentally relies on inducing an electrical current within the target material. If a material is an electrical insulator, no eddy currents can be formed, and therefore no heating will occur.

- Examples: Ceramics, glass, plastics, wood, and polymers.

These materials can, however, be heated indirectly by placing them in a conductive container (like a graphite crucible) and then using induction to heat the container. The container then transfers heat to the non-conductive material via conduction and radiation.

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Choosing the right heating method depends entirely on your material and your goal.

- If your primary focus is heating carbon steel or iron: Induction is an extremely efficient, fast, and precise method.

- If your primary focus is heating non-magnetic stainless steel or titanium: Induction is a very effective solution, though it may be slightly less energy-efficient than for carbon steel.

- If your primary focus is heating copper or aluminum: Induction is possible but requires specialized high-frequency equipment and will consume significantly more power, increasing operational costs.

- If your primary focus is heating ceramics, glass, or polymers: Direct induction heating will not work; you must use an indirect method by heating a conductive susceptor or crucible.

Ultimately, a material's success with induction heating is determined by its fundamental electrical and magnetic properties.

Summary Table:

| Efficiency Category | Key Properties | Example Metals | Heating Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Efficiency | Magnetic (Ferromagnetic), High Resistivity | Carbon Steel, Iron | Heats rapidly via hysteresis & eddy currents. |

| Moderate Efficiency | Non-Magnetic, Higher Resistivity | Stainless Steel (304/316), Titanium | Heats via eddy currents; requires standard power. |

| Low Efficiency | Non-Magnetic, Very Low Resistivity | Copper, Aluminum, Gold, Silver | Requires high-frequency, high-power equipment. |

| Cannot Be Heated (Directly) | Electrically Insulating | Ceramics, Glass, Plastics | Requires indirect heating via a conductive susceptor. |

Struggling to find the right heating solution for your unique materials?

Whether you're working with highly efficient carbon steel or challenging materials like copper and aluminum, KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnaces provide the precision and power you need. Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we offer a diverse product line—including Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems—complemented by strong deep customization capabilities to precisely meet your unique experimental requirements.

Let our experts help you optimize your thermal processing. Contact KINTEK today to discuss your application and discover a tailored solution that maximizes efficiency and performance.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- How does a laboratory muffle furnace facilitate the biomass carbonization process? Achieve Precise Biochar Production

- Why is a high-performance muffle furnace required for the calcination of nanopowders? Achieve Pure Nanocrystals

- What substances are prohibited from being introduced into the furnace chamber? Prevent Catastrophic Failure

- What role does a muffle furnace play in the preparation of MgO support materials? Master Catalyst Activation

- What environmental conditions are critical for SiOC ceramicization? Master Precise Oxidation & Thermal Control