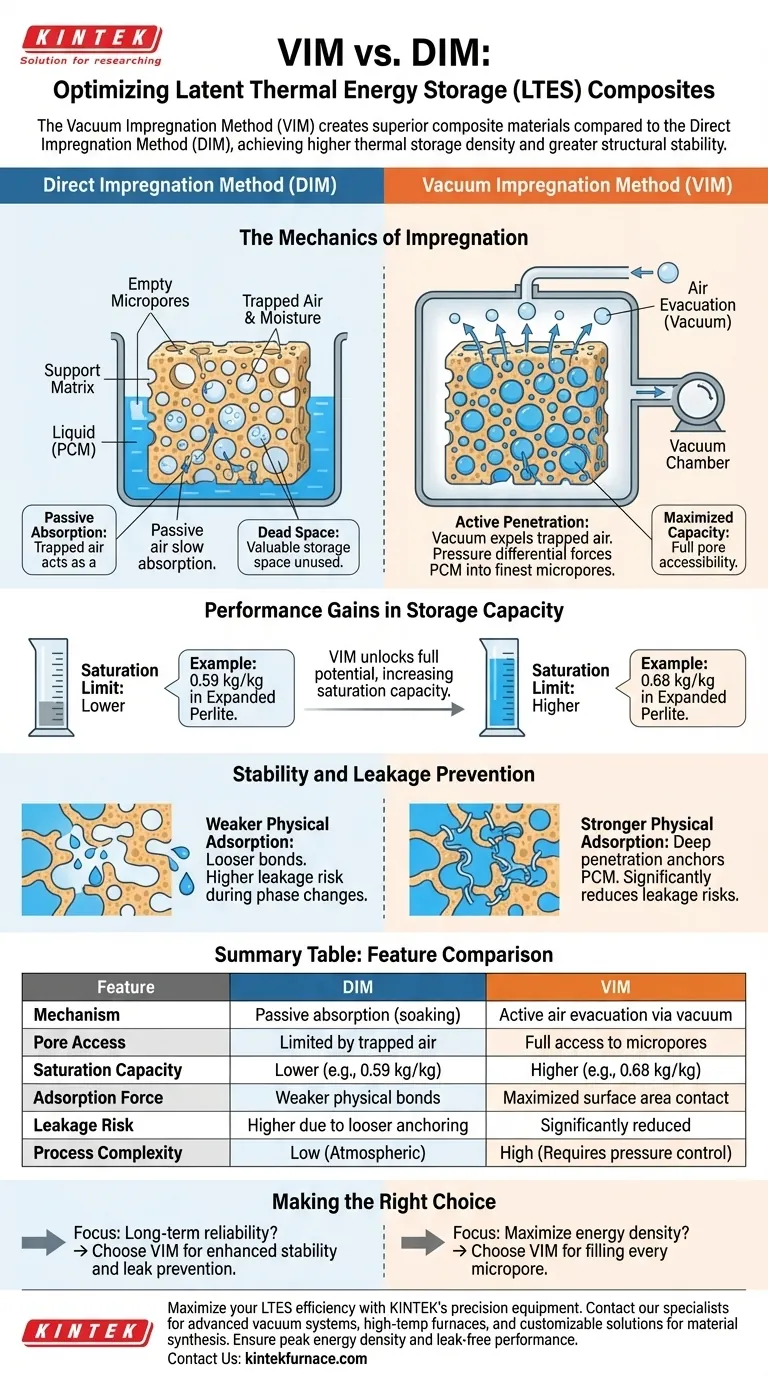

The Vacuum Impregnation Method (VIM) creates a superior composite material compared to the Direct Impregnation Method (DIM) by fundamentally changing how the Phase Change Material (PCM) enters the support structure. While DIM relies on passive absorption, VIM uses low-pressure environments to actively evacuate air and moisture, resulting in higher thermal storage density and greater structural stability.

The core difference lies in pore accessibility: VIM creates a vacuum that physically forces liquid PCM into microscopic pores that DIM leaves empty. This maximizes the material's energy storage capacity and significantly strengthens the bond between the PCM and its support matrix.

The Mechanics of Impregnation

Overcoming Air Resistance

In Direct Impregnation, air trapped inside the pores of the support material acts as a barrier. This prevents the liquid PCM from fully penetrating the matrix, leaving valuable storage space unused.

The Power of Pressure Differentials

VIM processes the porous support material under extremely low-pressure conditions. This creates a vacuum that forcibly expels the trapped air and moisture residing within the pores.

Active Penetration

Once the air is removed, a pressure differential is created. This differential acts as a driving force, pushing the liquid PCM deep into the finest micropores that standard soaking methods cannot reach.

Performance Gains in Storage Capacity

Increased Adsorption Rates

By removing the resistance caused by trapped gases, VIM significantly accelerates the adsorption rate. The porous matrix absorbs the PCM more rapidly and thoroughly than it does under atmospheric conditions.

Higher Saturation Limits

VIM unlocks the full potential of the support material. For example, in large-pore Expanded Perlite, VIM increases the saturation capacity to 0.68 kg/kg, compared to only 0.59 kg/kg achieved by DIM.

Stability and Leakage Prevention

Stronger Physical Adsorption

Because VIM drives the PCM into deeper, smaller pores, the surface area contact between the liquid and the solid matrix is maximized. This results in stronger physical adsorption forces holding the material together.

Reducing Leakage Risks

Leakage is a critical failure mode in LTES composites during phase change cycles (melting and freezing). By anchoring the PCM more securely within the micropores, VIM significantly reduces leakage risks compared to the looser bonds formed by DIM.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Limitations of Direct Impregnation (DIM)

While DIM is a simpler process, it inherently results in "dead space" within the composite. The inability to displace deep-seated air pockets limits the total energy density the material can hold.

The Necessity of Process Control

VIM is an active process requiring specific environmental controls (vacuum). However, this processing requirement is necessary to achieve the saturation capacities required for high-performance thermal storage applications.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The choice between these methods defines the efficiency and lifespan of your thermal storage system.

- If your primary focus is maximizing energy density: Use VIM to ensure every available micropore is filled, achieving capacities such as 0.68 kg/kg in expanded perlite composites.

- If your primary focus is long-term reliability: Choose VIM to enhance physical adsorption, ensuring the PCM remains trapped within the matrix to prevent leakage during repeated thermal cycles.

VIM transforms impregnation from a passive absorption process into a precision engineering step, ensuring your LTES composites deliver maximum capacity and stability.

Summary Table:

| Feature | Direct Impregnation Method (DIM) | Vacuum Impregnation Method (VIM) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Passive absorption (soaking) | Active air evacuation via vacuum |

| Pore Access | Limited by trapped air/moisture | Full access to micropores |

| Saturation Capacity | Lower (e.g., 0.59 kg/kg in Perlite) | Higher (e.g., 0.68 kg/kg in Perlite) |

| Adsorption Force | Weaker physical bonds | Maximized surface area contact |

| Leakage Risk | Higher due to looser anchoring | Significantly reduced via deep penetration |

| Process Complexity | Low (Atmospheric) | High (Requires pressure control) |

Maximize the efficiency of your Latent Thermal Energy Storage (LTES) projects with KINTEK's precision equipment. Backed by expert R&D and manufacturing, KINTEK offers advanced vacuum systems and lab high-temp furnaces—including Muffle, Tube, and CVD systems—all customizable for your unique material synthesis needs. Ensure your composites achieve peak energy density and leak-free performance. Contact our specialists today to find the perfect solution for your lab!

Visual Guide

References

- Chrysa Politi, I.P. Koronaki. Mechanistic Modelling for Optimising LTES-Enhanced Composites for Construction Applications. DOI: 10.3390/buildings15030351

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Furnace Knowledge Base .

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine for Lamination and Heating

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering and Brazing Furnace

- Laboratory Vacuum Tilt Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

- Ultra High Vacuum CF Flange Stainless Steel Sapphire Glass Observation Sight Window

People Also Ask

- What is the role of the power supply in an IGBT-based induction heater circuit? Unlock Maximum Heating Performance

- What role does the slitting design of a cold crucible play in ISM? Enhance Your Induction Skull Melting Efficiency

- What factors should be considered when selecting a crucible material for a vacuum casting furnace? Ensure Purity and Performance

- Why is superior temperature control accuracy important in induction furnaces? Ensure Metallurgical Quality & Cost Control

- What metals and alloys can be cast using induction furnaces? Unlock Precision Melting for All Conductive Metals

- What role does a Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM) furnace play in the recycling of low alloy steel? Ensure Purity.

- How does the alternating current power supply contribute to the induction heater's operation? Unlock Efficient, Contactless Heating

- How does precise temperature control in induction furnaces benefit gold melting? Maximize Purity & Minimize Loss