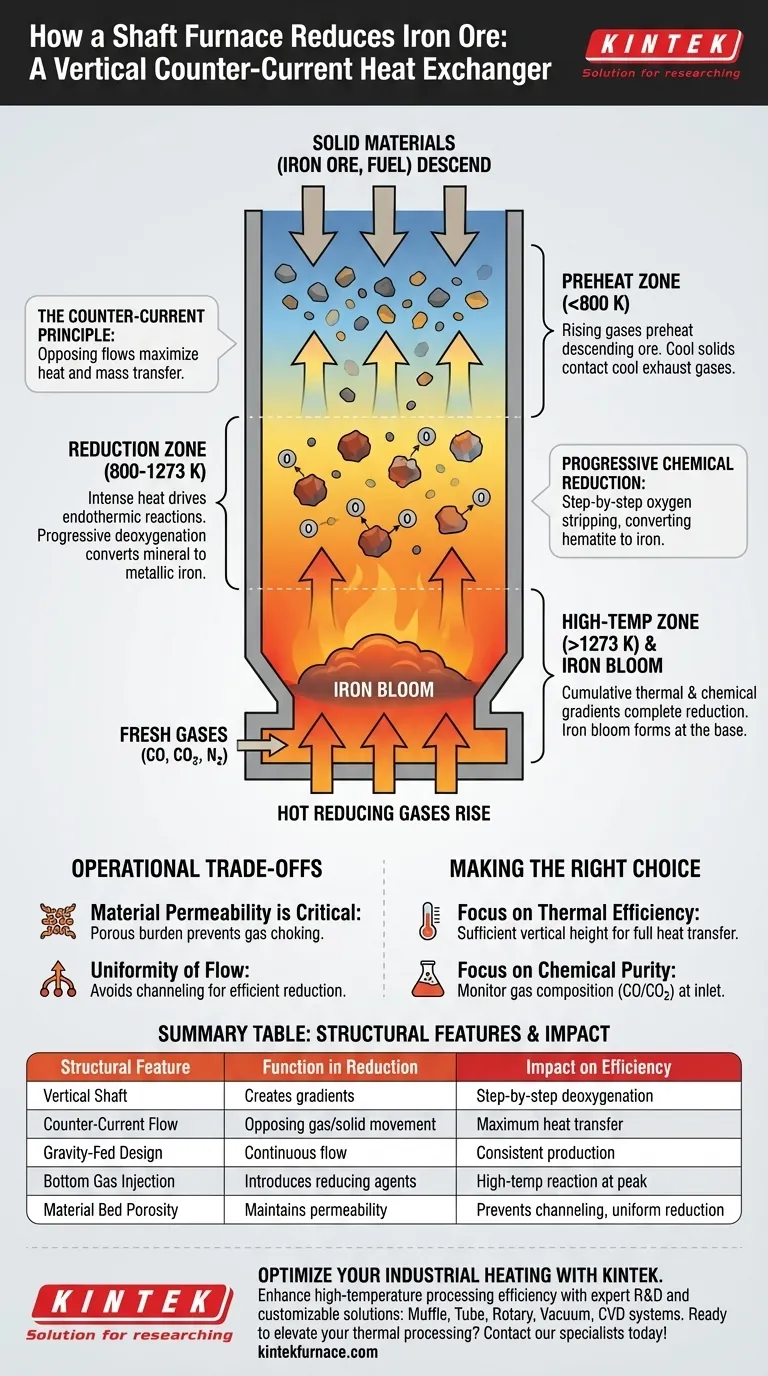

The structure of a shaft furnace functions as a vertical, counter-current heat exchanger. It utilizes gravity to feed solid materials (iron ore and fuel) downward, while forcing high-temperature reducing gases upward through the material bed, ensuring continuous physical contact and reaction.

The furnace's vertical height is not merely for capacity; it establishes critical thermal and chemical gradients. As materials descend, they pass through progressively hotter and more chemically active zones, ensuring the efficient deoxygenation of ore into metallic iron before it reaches the base.

The Mechanics of Vertical Reduction

The shaft furnace is designed to maximize the interaction between solids and gases. Its geometry solves the problem of heating large volumes of material evenly while simultaneously driving chemical changes.

The Counter-Current Principle

The core advantage of the shaft structure is the opposing flow of materials.

Iron ore and carbon sources, such as peat char, are introduced at the top.

Simultaneously, hot reducing gases rise from the bottom. This ensures that the coolest solids contact the coolest exhaust gases at the top, while the hottest solids at the bottom contact the freshest, hottest gases.

Establishing Thermal Gradients

The vertical channel creates a distinct temperature profile.

At the top, the rising gases preheat the descending ore, preparing it for reaction.

As the material moves lower, it encounters temperatures often exceeding 1273 K. This intense heat is necessary to drive the endothermic reactions required for reduction.

Progressive Chemical Reduction

The structure facilitates a step-by-step chemical transformation.

The rising gases typically contain controlled ratios of carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), and nitrogen (N2).

As the iron ore (specifically hematite) descends through these gas layers, it is progressively deoxygenated. The oxygen is stripped from the ore by the reducing gases, gradually converting the mineral into metallic iron.

Formation of the Iron Bloom

The process culminates at the furnace base.

By the time the material reaches the bottom, the cumulative effect of the thermal and chemical gradients has fully reduced the ore.

This results in the formation of an iron bloom—a mass of metallic iron and slag—which can then be extracted for further processing.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While the shaft furnace is highly efficient for heat transfer, its structural reliance on gravity and gas permeability creates specific operational constraints.

Material Permeability is Critical

Because gases must rise through the descending solids, the burden (the ore and fuel mix) must be porous.

If the materials are too fine or compact, they will choke the gas flow. This disrupts the thermal gradient and stops the reduction process.

Uniformity of Flow

The process relies on the uniform descent of solids and the uniform ascent of gases.

"Channeling"—where gas rushes up a single path of least resistance—can occur if the shaft is not loaded correctly. This leaves large sections of ore unreduced and wastes energy.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The shaft furnace design is specific to continuous, high-efficiency reduction. Understanding its structural principles allows you to control the quality of the output.

- If your primary focus is Thermal Efficiency: Ensure the vertical height is sufficient to allow exhaust gases to fully transfer their heat to the incoming ore before exiting the top.

- If your primary focus is Chemical Purity: Monitor the gas composition (CO vs. CO2 ratios) entering the bottom to ensure the reduction potential matches the descent rate of the ore.

The shaft furnace proves that geometry dictates chemistry; by controlling the vertical flow, you control the molecular transformation of the material.

Summary Table:

| Structural Feature | Function in Reduction | Impact on Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical Shaft | Creates thermal and chemical gradients | Step-by-step deoxygenation of ore |

| Counter-Current Flow | Opposing gas/solid movement | Maximum heat transfer from gas to ore |

| Gravity-Fed Design | Ensures continuous downward material flow | Consistent production without manual feeding |

| Bottom Gas Injection | Introduces hot reducing agents (CO) | High-temperature reaction at peak heat zone |

| Material Bed Porosity | Maintains gas permeability | Prevents 'channeling' and ensures uniform reduction |

Optimize Your Industrial Heating with KINTEK

Are you looking to enhance your high-temperature processing efficiency? Backed by expert R&D and world-class manufacturing, KINTEK provides high-performance heating solutions including Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum, and CVD systems. Whether you are refining iron ore or conducting advanced material research, our systems are fully customizable to meet your unique laboratory or industrial needs.

Ready to elevate your thermal processing? Contact our specialists today to find your perfect furnace solution!

Visual Guide

References

- Paul M. Jack. Feeling the Peat: Investigating peat charcoal as an iron smelting fuel for the Scottish Iron Age. DOI: 10.54841/hm.682

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Furnace Knowledge Base .

Related Products

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory Debinding and Pre Sintering

People Also Ask

- What is the function of a laboratory hot air drying oven in TiO2 treatment? Ensure Uniform Nanoparticle Quality

- Why is a constant temperature drying oven necessary during the preparation of porous activated carbon? Key Benefits

- What unique advantages does microwave heating equipment provide for iron-containing dust reduction? Boost Recovery Rates

- What are the process advantages of using an electric melting furnace with an adjustable thermostat? Optimize Copper Scrap Refining

- Why is a laboratory blast drying oven necessary for preparing Reduced Graphene Oxide precursors? Ensure Powder Quality

- How does Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA/DTG) provide industrial guidance? Optimize Blast Furnace Dust Treatment

- What are the advantages of using a microwave reaction system? Rapid & Uniform Synthesis of Doped Hydroxyapatite

- Why is a temperature-controlled heating system required for firing silver electrodes? Ensure Precision Ohmic Contacts