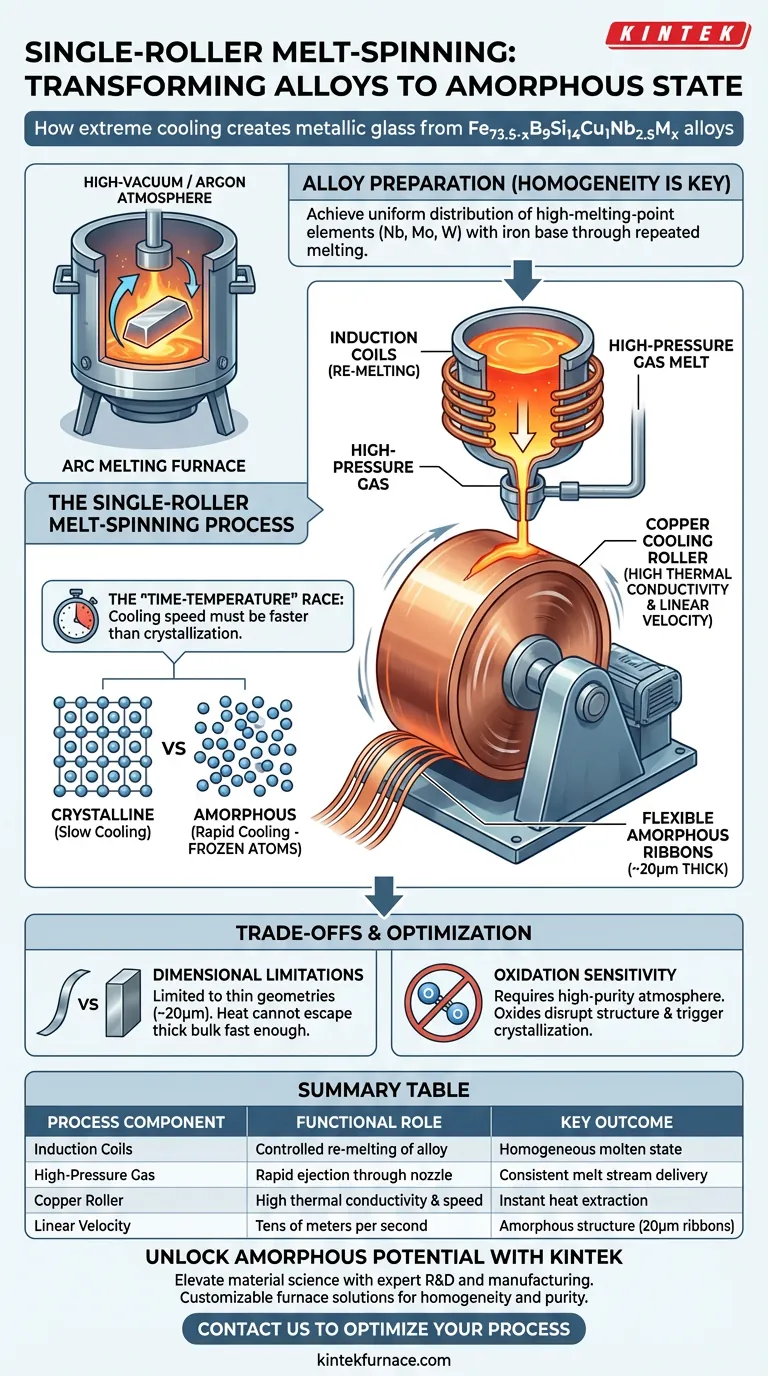

The single-roller melt-spinning system facilitates amorphization by subjecting the molten alloy to an extreme cooling rate that prevents crystallization.

For the Fe73.5-xB9Si14Cu1Nb2.5Mx alloy, the system operates by re-melting the ingot using induction coils and ejecting the melt via high-pressure gas onto a rapidly rotating copper roller. The roller's high linear velocity instantly extracts heat, freezing the atoms in a disordered state to form flexible amorphous ribbons approximately 20 microns thick.

The essence of this process is the "time-temperature" race: the cooling speed generated by the spinning roller must be faster than the time required for atoms to organize into a crystal lattice.

The Mechanics of Rapid Solidification

Re-melting and Injection

The process begins by taking the pre-alloyed ingot and re-melting it inside the spinning system using induction coils.

Once the alloy is fully molten, high-pressure gas is utilized to force the liquid metal through a nozzle.

This ejection directs a precise stream of molten material onto the cooling surface below.

The Role of the Copper Roller

The core component of the system is a copper cooling roller that rotates at extremely high speeds.

Copper is selected for its high thermal conductivity, acting as an immediate heat sink for the molten stream.

The roller achieves a linear velocity of tens of meters per second, which is critical for dragging the melt into a thin layer.

Locking the Atomic Structure

The contact between the molten stream and the hyper-fast roller creates a massive temperature gradient.

This results in a rapid cooling rate that instantaneously lowers the temperature of the alloy.

Because the cooling is so abrupt, the atoms are frozen in their disordered positions before they can nucleate or arrange into a crystalline structure.

The Importance of Alloy Preparation

While the melt-spinner creates the amorphous state, the quality of the outcome depends on the precursor ingot.

Achieving Homogeneity

Before melt-spinning, the Fe73.5-xB9Si14Cu1Nb2.5Mx ingot must be prepared in an arc melting furnace.

This step ensures high-melting-point elements like niobium, molybdenum, or tungsten are completely melted and mixed with the iron base.

Ensuring Uniform Distribution

The arc melting process involves repeatedly flipping and re-melting the ingot.

This guarantees that transition metals with varying atomic masses achieve a highly uniform macroscopic distribution.

Without this homogeneity, the melt-spinning process might result in inconsistent amorphous properties across the ribbon.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Dimensional Limitations

The physics of this cooling method imposes strict size constraints.

To maintain the cooling rate required for amorphization, the product is limited to thin geometries, typically ribbons around 20 microns thick.

You cannot produce bulk, thick components using a single-roller system because the heat cannot escape the center of the material fast enough to prevent crystallization.

Sensitivity to Oxidation

The presence of oxides can disrupt the amorphous structure.

The precursor preparation relies on a high-vacuum and high-purity argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation.

If oxygen contaminates the melt during either arc melting or spinning, it can trigger unwanted crystallization.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

- If your primary focus is creating a fully amorphous structure: Ensure the roller's linear velocity is maximized to "outrun" the crystallization kinetics of the alloy.

- If your primary focus is material consistency: Verify that the precursor ingot was flipped and melted multiple times in the arc furnace to fully disperse high-melting-point elements.

By combining precise precursor homogenization with the extreme cooling rates of the single-roller system, you effectively lock this complex alloy into a high-performance metallic glass.

Summary Table:

| Process Component | Functional Role | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Induction Coils | Controlled re-melting of alloy ingot | Homogeneous molten state |

| High-Pressure Gas | Rapid ejection through precision nozzle | Consistent melt stream delivery |

| Copper Roller | High thermal conductivity & high-speed rotation | Instant heat extraction |

| Linear Velocity | Tens of meters per second | Amorphous structure (20μm ribbons) |

Unlock the Potential of Amorphous Metal Research

Elevate your material science capabilities with KINTEK. Backed by expert R&D and manufacturing, we provide high-performance Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum, and CVD systems, alongside specialized lab equipment for high-temperature synthesis.

Whether you are processing Fe-based alloys or developing custom metallic glasses, our customizable furnace solutions ensure the homogeneity and purity your research demands.

Ready to optimize your rapid solidification process? Contact us today to discuss your unique project needs with our technical specialists!

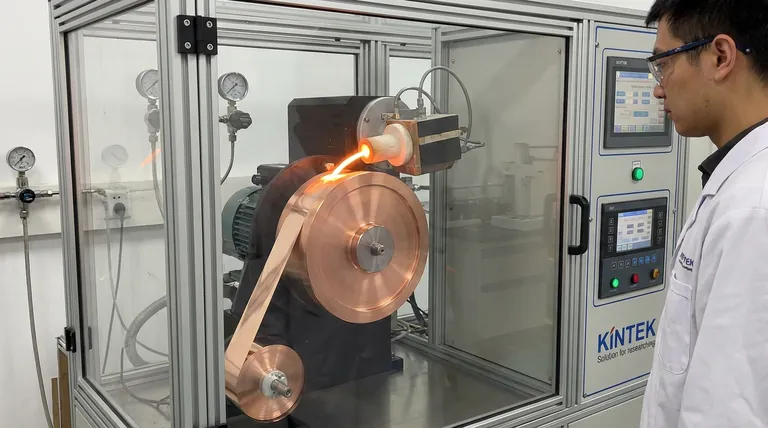

Visual Guide

References

- Subong An, Jae Won Jeong. Fine-Grained High-Permeability Fe73.5−xB9Si14Cu1Nb2.5Mx (M = Mo or W) Nanocrystalline Alloys with Co-Added Heterogeneous Transition Metal Elements. DOI: 10.3390/met14121424

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Furnace Knowledge Base .

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace Molybdenum Wire Vacuum Sintering Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Mesh Belt Controlled Atmosphere Furnace Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering and Brazing Furnace

People Also Ask

- How does a constant temperature drying oven facilitate solvent removal? Optimize Perovskite Nanocrystal Synthesis

- Why is graphite furnace AAS more sensitive than flame AAS? Unlocking Trace-Level Detection

- What is the use of dental ceramic? Achieve Lifelike, Durable, and Biocompatible Restorations

- How does a vacuum oven contribute to the performance of composite electrode slurries? Enhance Battery Life & Stability

- Why is a 105 °C drying process in an electric drying oven significant? Prevent Refractory Structural Failure

- Why is XPS used to analyze manganese catalysts? Master Surface Valence States for Enhanced Reactivity

- What is the primary function of a vacuum oven for Mo-based catalyst precursors? Ensure Purity & Pore Integrity

- Why is a constant temperature drying oven necessary for CN/BOC-X composites? Ensure High Photocatalytic Activity