At its core, induction technology can process virtually any material that is electrically conductive. This includes a vast range of metals from various steels and copper alloys to aluminum, titanium, silicon, and precious metals. Even advanced materials like graphite and some composites can be effectively heated using this method.

The essential requirement for induction processing is not magnetism, but electrical conductivity. A material's ability to conduct an electrical current determines if it can be heated by induction, while its magnetic properties primarily influence how efficiently and quickly this heating occurs.

The Fundamental Principle: Electrical Conductivity

Induction works by creating electrical currents within the material itself. Understanding this principle is key to knowing which materials are suitable candidates.

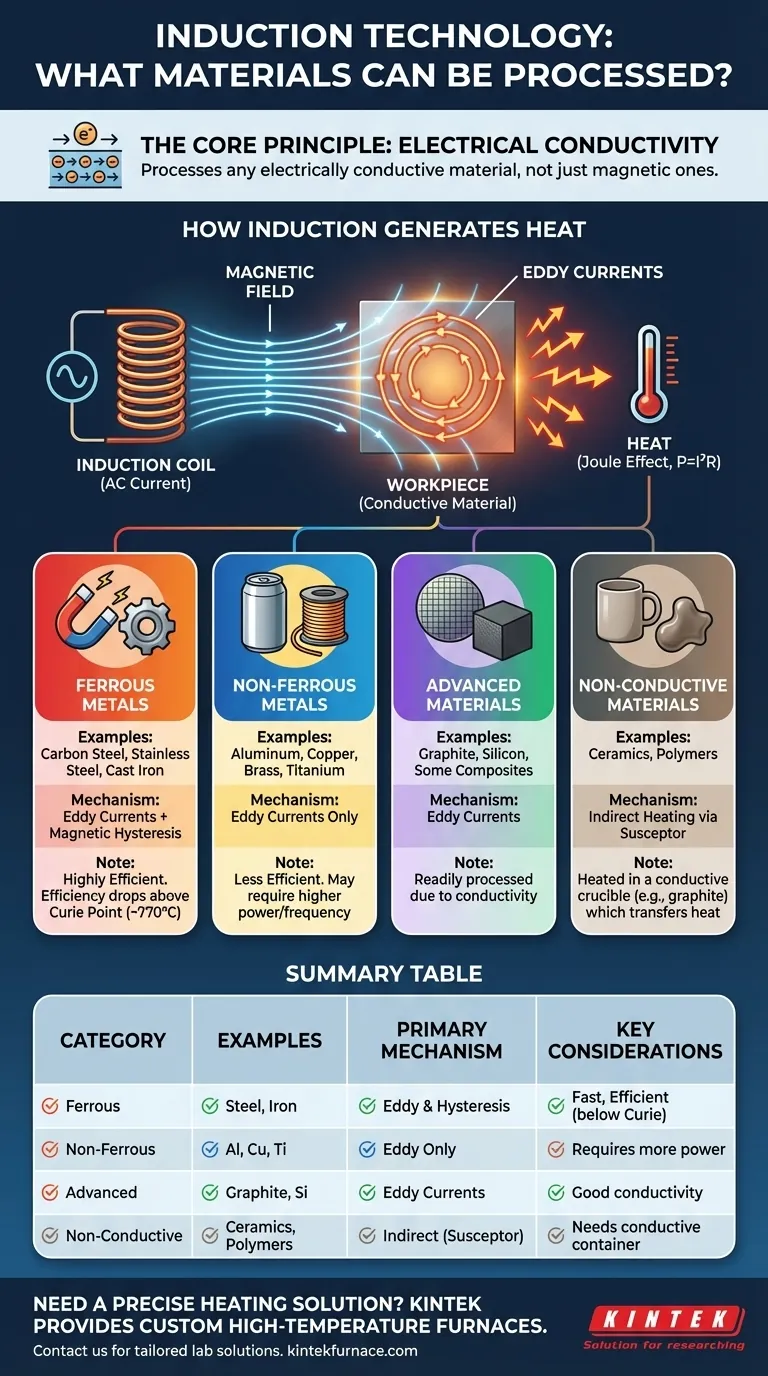

How Induction Generates Heat

Think of an induction coil as the primary of a transformer, and the workpiece (the material to be heated) as a single-turn secondary. When alternating current flows through the coil, it creates a powerful, rapidly changing magnetic field.

This magnetic field induces circulating electrical currents within the workpiece, known as eddy currents. The material's natural resistance to the flow of these currents generates precise and instantaneous heat, a phenomenon described by the Joule effect (P = I²R).

The Critical Role of Resistivity

A material's electrical resistivity determines how effectively the induced eddy currents are converted into thermal energy.

Materials with extremely high conductivity, like pure copper, can actually be more difficult to heat. They allow eddy currents to flow so easily that less energy is converted into heat, often requiring higher frequencies or more power to compensate. Conversely, materials with higher resistivity (like steel) heat up more readily.

Key Material Categories and Their Behavior

While conductivity is the prerequisite, a material's magnetic properties create a second, powerful heating mechanism, dividing most metals into two distinct groups for induction purposes.

Ferrous Metals: The Efficiency Champions

Ferrous metals like carbon steel, stainless steel, and cast iron are ideal for induction. They heat through two mechanisms simultaneously.

First, they generate heat from eddy currents, just like any other conductor.

Second, below a certain temperature (the Curie point), their magnetic nature creates an additional heating effect through magnetic hysteresis. As the rapidly changing magnetic field forces the material's magnetic domains to flip back and forth, it creates internal friction, which generates significant heat. This dual-action makes heating ferrous metals extremely fast and efficient.

Non-Ferrous Metals: Relying on Eddy Currents

Non-ferrous metals like aluminum, copper, brass, and titanium are not magnetic. Therefore, they can only be heated by the single mechanism of eddy currents.

While still highly effective, heating these materials is generally less efficient than heating ferrous metals. Achieving desired temperatures or heat rates often requires using higher frequencies to concentrate the currents near the surface (the skin effect) or applying more overall power.

Advanced and Non-Metallic Materials

Induction is not limited to traditional metals. Materials like graphite and silicon, which are conductive, are readily processed.

Furthermore, even non-conductive materials like ceramics or polymers can be heated indirectly. This is achieved by placing them in a conductive container, often a graphite crucible, which is then heated by the induction field. The crucible, known as a susceptor, transfers its heat to the non-conductive material via conduction and radiation.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing induction requires understanding how a material's properties interact with the process parameters.

The Curie Point: A Critical Temperature Threshold

For ferrous metals, the powerful hysteresis heating effect disappears once the material is heated above its Curie temperature (around 770°C or 1420°F for steel).

Above this point, the steel becomes non-magnetic and heats only via eddy currents, just like aluminum. This causes a noticeable drop in heating efficiency, a critical factor that must be accounted for in processes like hardening or forging.

The Impact of Geometry and Mass

The shape and thickness of a part significantly influence how it interacts with the magnetic field. Induction heating is a surface-level phenomenon due to the skin effect, where currents concentrate near the surface.

Thin parts or materials with complex geometries may require different coil designs or frequencies to ensure uniform heating compared to large, solid billets.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The suitability of induction depends on matching the material's properties to your specific processing objective.

- If your primary focus is rapid heating of steel or iron: You can leverage magnetic hysteresis for exceptionally fast and energy-efficient processing for applications like hardening, tempering, and forging.

- If your primary focus is melting or annealing aluminum, brass, or copper: Be prepared to use higher power or frequency to compensate for the lack of magnetic heating and, in the case of copper, very high electrical conductivity.

- If your primary focus is processing non-metals, powders, or liquids: Plan to use a conductive susceptor or crucible made of a material like graphite for effective indirect heating.

Ultimately, understanding the interplay between a material's conductive and magnetic properties empowers you to design an optimal and efficient induction process.

Summary Table:

| Material Category | Key Examples | Primary Heating Mechanism | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous Metals | Carbon Steel, Stainless Steel, Cast Iron | Eddy Currents & Magnetic Hysteresis | Highly efficient; heating rate slows above the Curie point (~770°C). |

| Non-Ferrous Metals | Aluminum, Copper, Brass, Titanium | Eddy Currents Only | Requires higher power/frequency; less efficient than ferrous metals. |

| Advanced Materials | Graphite, Silicon | Eddy Currents | Readily processed due to good electrical conductivity. |

| Non-Conductive Materials | Ceramics, Polymers | Indirect Heating (via a susceptor) | Requires a conductive crucible (e.g., graphite) to transfer heat. |

Need a Precise Heating Solution for Your Specific Materials?

Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, KINTEK provides diverse laboratories with advanced high-temperature furnace solutions. Our product line, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems, is complemented by our strong deep customization capability to precisely meet unique experimental requirements.

Whether you are working with highly conductive non-ferrous metals, advanced composites, or require indirect heating for sensitive materials, our team can design a system optimized for your application.

Contact us today to discuss your material processing challenges and discover how our tailored solutions can enhance your lab's efficiency and results.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Induction Melting Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

People Also Ask

- What role does a vacuum induction melting furnace play in Fe-5%Mn-C alloys? Ensure Chemical Integrity and High Purity

- Why is a Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM) furnace essential? Unlock Purity for Aerospace and Semiconductors

- What is the purpose of vacuum melting, casting and re-melting equipment? Achieve High-Purity Metals for Critical Applications

- What are the core functions of the High Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM) furnace? Optimize DD5 Superalloy Purification

- How has vacuum smelting impacted the development of superalloys? Unlock Higher Strength and Purity