At its core, annealing is a controlled heat treatment process used to make a material, typically a metal, softer, more ductile, and easier to work with. It achieves this by fundamentally altering the material's internal microstructure, relieving stresses introduced during manufacturing processes like bending, rolling, or drawing.

The central purpose of annealing is not merely to soften a material, but to "reset" its internal crystalline structure. It reverses the hardening and brittleness caused by physical manipulation (work hardening), restoring the material's workability and uniformity.

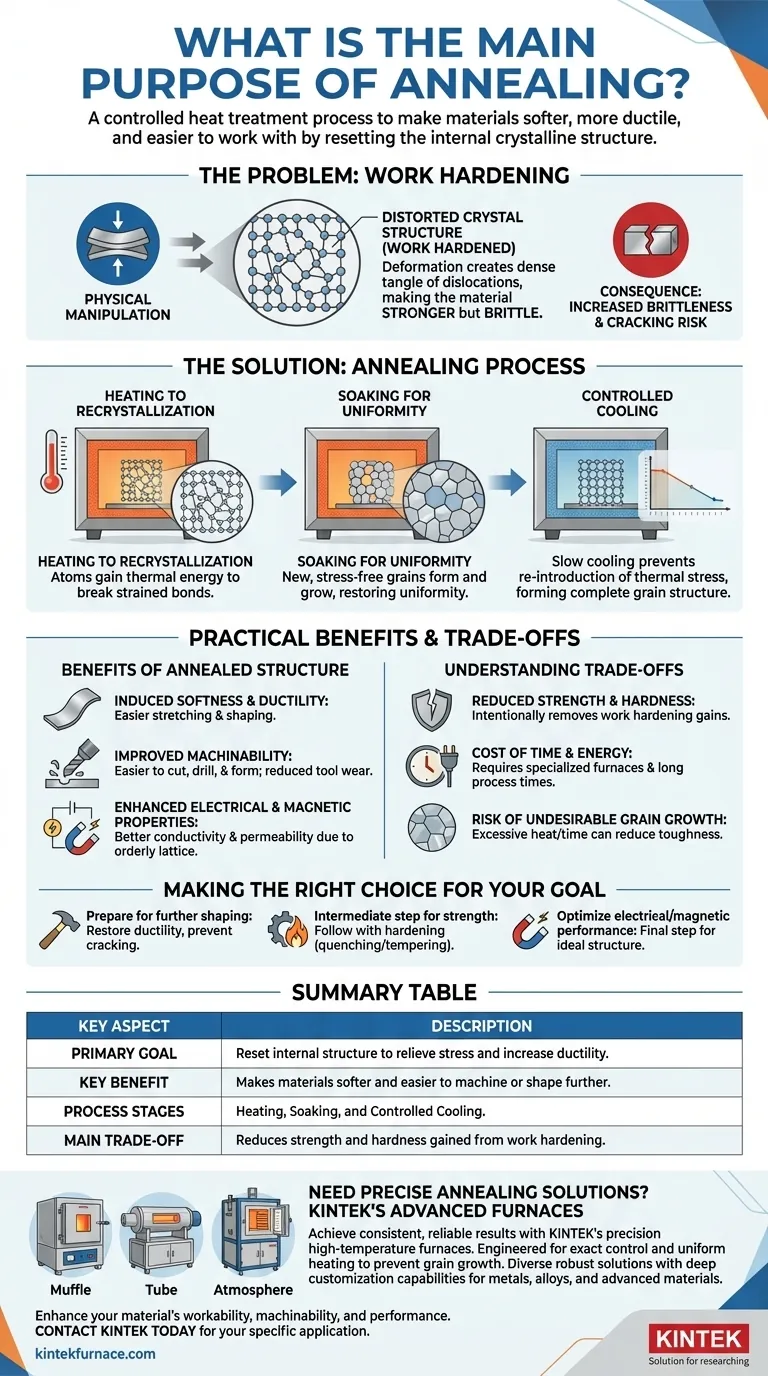

The Problem: Why Materials Need Annealing

Before understanding the solution, it's critical to understand the problem it solves: work hardening.

The Effect of Work Hardening

When you bend, stretch, or hammer a piece of metal at room temperature, you are physically deforming its internal crystal structure. This process is called work hardening or strain hardening.

These deformations create a dense tangle of dislocations within the material's atomic lattice. This makes the material stronger and harder, but it also makes it significantly more brittle and less ductile.

The Consequences of Brittleness

A work-hardened material has lost most of its ability to be shaped further. Trying to bend or form it again will likely cause it to crack or fracture instead of deforming smoothly. This internal stress is the primary problem that annealing is designed to eliminate.

The Solution: How Annealing Works

Annealing is a precise, three-stage process that gives the material's internal structure the energy and time it needs to repair itself.

Stage 1: Heating to Recrystallization

First, the material is heated to a specific temperature, known as its recrystallization temperature. At this point, the atoms have enough thermal energy to break their strained bonds and begin moving into new positions.

Stage 2: Soaking for Uniformity

The material is then held at this elevated temperature for a set period, a stage called soaking. During this time, new, stress-free crystal grains begin to form and grow, gradually replacing the deformed, stressed grains created by work hardening.

Stage 3: Controlled Cooling

Finally, the material is cooled at a very slow and controlled rate. This slow cooling is critical because it allows the new, orderly grain structure to form completely without re-introducing thermal stress. Rapid cooling (quenching) would have the opposite effect, trapping stress and hardening the metal.

The Practical Benefits of an Annealed Structure

This "reset" of the internal grain structure results in several highly desirable changes in the material's properties.

Induces Softness and Ductility

The new, uniform, and stress-free grains can slide past one another much more easily. This directly translates to a decrease in hardness and a significant increase in ductility, which is the ability to be stretched or shaped without breaking.

Improves Machinability

A softer, less brittle material is much easier to cut, drill, and form. Annealing improves machinability, leading to reduced tool wear, better surface finishes, and lower energy consumption during manufacturing.

Enhances Electrical and Magnetic Properties

The internal defects and stresses from work hardening impede the flow of electrons and the alignment of magnetic domains. By creating a more perfect and orderly crystal lattice, annealing can significantly improve electrical conductivity and magnetic permeability.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While powerful, annealing is a deliberate choice with clear consequences that must be understood.

Reduced Strength and Hardness

The primary trade-off is straightforward: annealing makes a material softer. The process intentionally removes the hardness and strength gained from work hardening. If the final product requires high strength, annealing is often an intermediate step, not the final one.

The Cost of Time and Energy

Annealing requires specialized furnaces capable of precise temperature control. The process, especially the slow cooling phase, can take many hours, consuming significant time and energy, which adds to the overall cost of production.

Risk of Undesirable Grain Growth

If the annealing temperature is too high or the soaking time is too long, the new crystal grains can grow excessively large. In some applications, overly large grains can reduce a material's toughness or other desired mechanical properties.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Applying annealing effectively depends entirely on what you want to achieve with the material.

- If your primary focus is preparing a material for further shaping: Annealing is essential to relieve work hardening, restore ductility, and prevent cracking during subsequent forming operations.

- If your primary focus is maximizing a finished part's strength: Annealing is likely an intermediate step to make fabrication possible, which will be followed by a final hardening process like quenching and tempering.

- If your primary focus is optimizing electrical or magnetic performance: Annealing is a critical final step to create the ideal, stress-free internal structure needed for maximum conductivity or permeability.

Ultimately, annealing provides a powerful method for deliberately controlling a material's fundamental properties to meet a specific engineering goal.

Summary Table:

| Key Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Reset internal structure to relieve stress and increase ductility. |

| Key Benefit | Makes materials softer and easier to machine or shape further. |

| Process Stages | Heating, Soaking, and Controlled Cooling. |

| Main Trade-off | Reduces strength and hardness gained from work hardening. |

Need Precise Annealing for Your Materials?

Understanding the theory is the first step; achieving consistent, reliable results requires the right equipment. The annealing process demands exact temperature control and uniform heating to successfully reset your material's microstructure without causing undesirable grain growth.

KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnaces are engineered for this precision. Leveraging our exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with robust annealing solutions. Our product line, including Muffle, Tube, and Atmosphere Furnaces, is complemented by strong deep customization capabilities to meet your unique process requirements—whether you're working with metals, alloys, or advanced materials.

Let us help you enhance your material's workability, machinability, and performance.

Contact KINTEK today to discuss your specific annealing application and discover how our solutions can bring reliability and efficiency to your lab.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory Debinding and Pre Sintering

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

People Also Ask

- What environmental conditions are critical for SiOC ceramicization? Master Precise Oxidation & Thermal Control

- What is the role of a muffle furnace in the synthesis of water-soluble Sr3Al2O6? Precision in SAO Production

- What is the key role of a muffle furnace in the pretreatment of boron sludge and szaibelyite? Unlock Higher Process Efficiency

- How does a laboratory muffle furnace facilitate the biomass carbonization process? Achieve Precise Biochar Production

- What is the role of a muffle furnace in the study of biochar regeneration and reuse? Unlock Sustainable Water Treatment