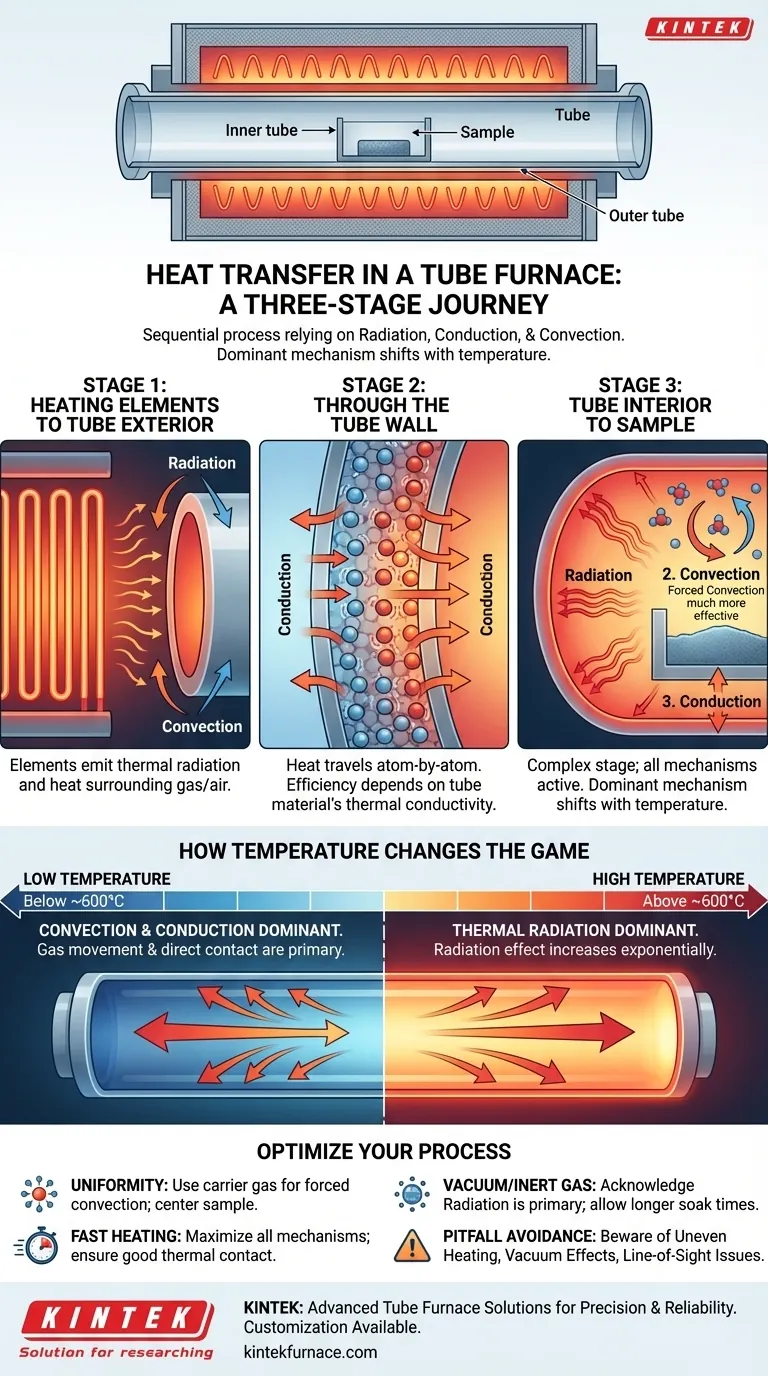

In a tube furnace, heat is transferred to the material inside through a sequential, three-stage process. First, energy moves from the external heating elements to the furnace tube's outer surface. It then travels through the tube wall itself, and finally, it is distributed from the tube's inner surface to your sample. This entire journey relies on a combination of three fundamental heat transfer mechanisms: radiation, conduction, and convection.

The core principle to grasp is that heat transfer in a tube furnace is not a single event, but a chain reaction. The dominant transfer mechanism—radiation, conduction, or convection—changes at each stage of the journey from the heating element to your sample, and its importance shifts 드라마ically with temperature.

The Three-Stage Journey of Heat

Understanding how heat moves is critical for achieving uniform and repeatable results. The process can be broken down into three distinct stages.

Stage 1: From Heating Elements to the Tube Exterior

The process begins with the heating elements, which are typically made of electrical resistance wire or ceramic composites. These elements transfer heat to the outside of the process tube.

Two mechanisms are at play here. The glowing hot elements emit thermal radiation, electromagnetic waves that travel through the space and are absorbed by the tube's outer wall. Simultaneously, the elements heat the air or insulation around the tube, which then transfers heat via convection.

Stage 2: Through the Tube Wall

Once the outer surface of the tube is hot, that thermal energy must travel to the inner surface. This happens exclusively through thermal conduction.

Heat energy excites the atoms in the tube material (e.g., quartz, alumina, or mullite), causing them to vibrate and pass that energy along atom by atom. The efficiency of this step depends entirely on the thermal conductivity of the tube material.

Stage 3: From the Tube Interior to the Sample

This is the most complex stage, where all three heat transfer modes can be active. The hot inner wall of the tube now acts as the heat source for your sample.

- Radiation: The inner tube wall, now at a high temperature, radiates heat directly to the surface of the sample. This is a non-contact, "line-of-sight" transfer.

- Convection: If a gas (such as air, nitrogen, or argon) is present in the tube, the tube wall heats this gas. The gas then circulates, transferring heat to the sample. If you are flowing gas through the tube, this becomes forced convection, a much more effective way to ensure uniform heating.

- Conduction: If your sample is resting directly on the bottom of the tube, heat is transferred through direct physical contact.

How Temperature Changes the Game

The efficiency and dominance of these mechanisms are not static; they change significantly as the furnace temperature rises.

At Lower Temperatures (Below ~600°C)

At lower temperatures, convection and conduction are the most significant methods of heat transfer inside the tube. The movement of gas and direct physical contact are responsible for the majority of the heating.

At Higher Temperatures (Above ~600°C)

As the temperature climbs, the inner wall of the tube begins to glow. At this point, thermal radiation becomes the dominant and most powerful heat transfer mechanism. The amount of energy transferred by radiation increases exponentially with temperature, quickly dwarfing the effects of convection and conduction.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

A failure to understand these principles can lead to failed experiments and inconsistent results.

The Risk of Uneven Heating

Relying solely on conduction by placing a sample container directly on the tube floor can create a significant temperature gradient. The bottom of your sample will be much hotter than the top, which is only being heated by a combination of convection and radiation.

The Impact of Atmosphere

Heating a sample in a vacuum is very different from heating it in a gas. In a vacuum, convection is eliminated entirely. Heat transfer relies only on radiation and any direct conduction. This can lead to slower heating cycles but may be necessary for atmosphere-sensitive materials.

The "Line-of-Sight" Problem

Since radiation travels in straight lines, parts of a complex or large sample can "shadow" other parts, preventing them from receiving direct radiated heat. This can create cool spots and non-uniformity across the sample.

How to Apply This to Your Process

Your heating strategy should be tailored to your experimental goal.

- If your primary focus is maximum temperature uniformity: Use a carrier gas to introduce forced convection, and place your sample in the center of the tube (e.g., in a smaller boat) to ensure it receives even radiation from all sides.

- If your primary focus is the fastest possible heating rate: Maximize all three mechanisms by using a high-flow carrier gas (forced convection) and ensuring good thermal contact between the sample and its holder.

- If your primary focus is processing in a vacuum or inert gas: Acknowledge that radiation is your primary tool. Allow for longer "soak" times at the target temperature to give the sample time to reach thermal equilibrium.

By understanding the distinct roles of radiation, conduction, and convection, you can exert precise control over your thermal process.

Summary Table:

| Stage | Heat Source | Heat Transfer Mechanism(s) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: From Heating Elements to Tube Exterior | External heating elements | Radiation, Convection | Elements emit thermal radiation and heat surrounding gas/air |

| 2: Through the Tube Wall | Tube's outer surface | Conduction | Depends on tube material's thermal conductivity (e.g., quartz, alumina) |

| 3: From Tube Interior to Sample | Tube's inner surface | Radiation, Convection, Conduction | Dominant mechanism shifts with temperature; radiation prevails above ~600°C |

Optimize Your Thermal Processes with KINTEK's Advanced Tube Furnaces

Struggling with uneven heating or slow ramp rates in your experiments? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide diverse laboratories with tailored high-temperature furnace solutions. Our product line, including Tube Furnaces, Muffle Furnaces, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems, is designed for precision and reliability. With strong deep customization capabilities, we can adapt our furnaces to meet your unique experimental requirements—ensuring uniform heat transfer, faster cycles, and repeatable results.

Ready to enhance your lab's efficiency? Contact us today to discuss how our tube furnaces can solve your specific challenges!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

- 1400℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz and Alumina Tube

- Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace RTP Heating Tubular Furnace

- Split Multi Heating Zone Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- How is a high-temperature tube furnace utilized in the synthesis of MoO2/MWCNTs nanocomposites? Precision Guide

- How is a Vertical Tube Furnace used for fuel dust ignition studies? Model Industrial Combustion with Precision

- How does a vertical tube furnace achieve precise temperature control? Unlock Superior Thermal Stability for Your Lab

- Why is a tube furnace utilized for the heat treatment of S/C composite cathode materials? Optimize Battery Stability

- What role does a laboratory tube furnace perform during the carbonization of LCNSs? Achieve 83.8% Efficiency