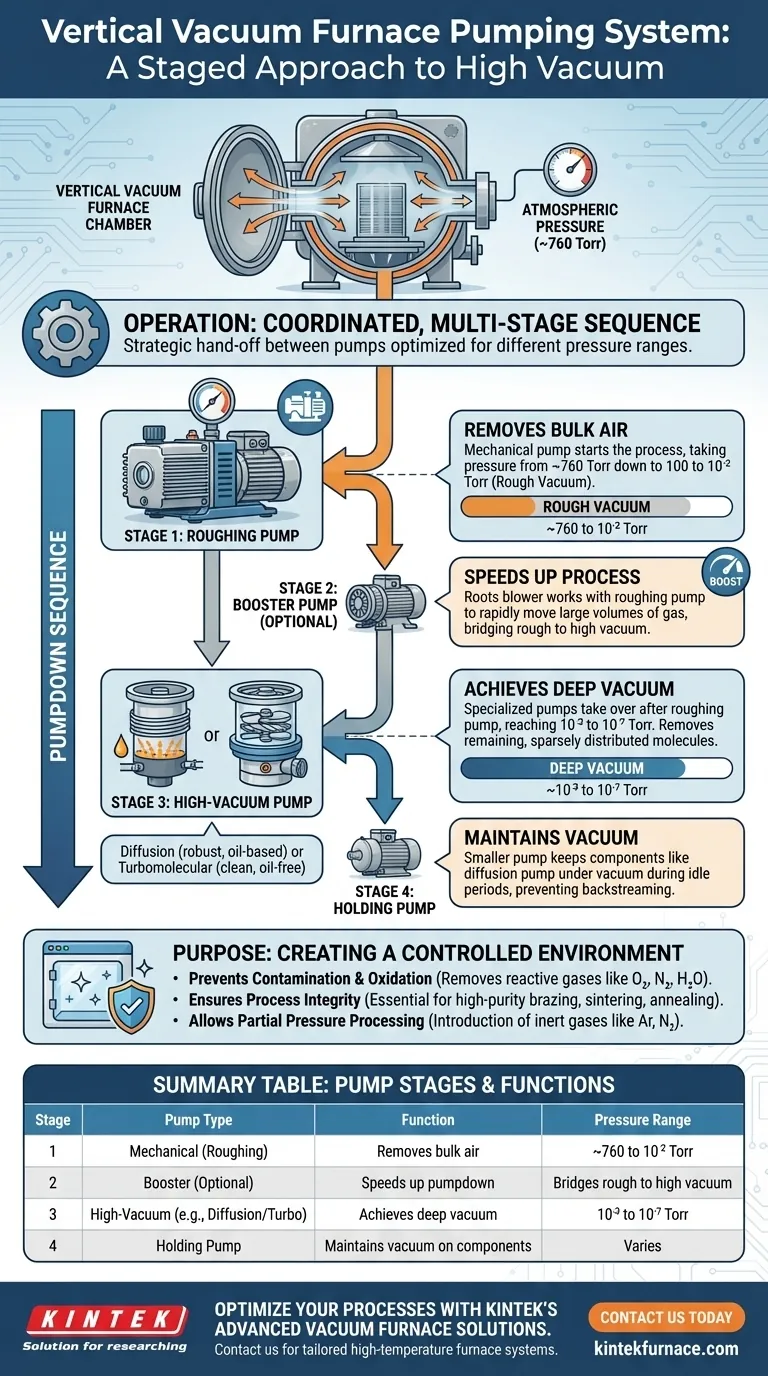

In a vertical vacuum furnace, the pumping system does not rely on a single pump but operates as a coordinated, multi-stage sequence. It begins with a mechanical "roughing" pump to remove the bulk of the air from the chamber. As the pressure drops, specialized high-vacuum pumps, such as diffusion or turbomolecular pumps, take over to achieve the extremely low pressures required for sensitive metallurgical processes.

The core principle is not about a single pump, but a strategic hand-off. Different pumps are optimized for different pressure ranges, and they work in a specific sequence to efficiently take the furnace chamber from atmospheric pressure down to a deep vacuum.

The Purpose of the Vacuum System: Creating a Controlled Environment

The primary goal of the vacuum system is to remove the atmosphere—primarily oxygen, nitrogen, and water vapor—from the heating chamber. This creates a predictable and pure environment essential for high-temperature material processing.

Preventing Contamination and Oxidation

At high temperatures, reactive gases like oxygen will readily bond with the surface of metal parts, forming oxides and other contaminants. This can ruin the material's properties, surface finish, and integrity.

By removing these gases, the vacuum system ensures the heat treatment process occurs without unwanted chemical reactions.

Ensuring Process Integrity

Many advanced processes, such as brazing, sintering, and certain types of annealing, require an exceptionally clean environment. The absence of atmospheric gases prevents interference with the process, ensuring strong brazed joints or proper material densification.

The system also allows for the introduction of specific inert gases (like argon or nitrogen) at controlled low pressures, a technique known as partial pressure processing, to achieve specific metallurgical outcomes.

The Pumpdown Sequence: A Staged Approach to Vacuum

Achieving a high vacuum is a journey through dramatically different pressure regimes. The furnace's pumping system uses a series of pumps, each designed to operate most effectively in one of these regimes.

Stage 1: The Roughing Pump

The process always starts with a mechanical pump, often called a roughing pump. Its job is to do the initial heavy lifting.

This pump removes the vast majority of air molecules, taking the chamber from atmospheric pressure (approx. 760 Torr) down to a "rough vacuum" level (typically in the range of 100 to 10⁻² Torr).

Stage 2: The Booster Pump (Optional)

To speed up the process, a booster pump (such as a Roots blower) may be used. It works in tandem with the roughing pump.

The booster activates once a certain rough vacuum is reached and rapidly moves large volumes of gas, bridging the gap between the roughing and high-vacuum stages. This significantly reduces overall pumpdown time.

Stage 3: The High-Vacuum Pump

High-vacuum pumps cannot operate at atmospheric pressure and only become effective once the roughing pump has done its job. Their function is to remove the remaining, sparsely distributed molecules.

Common types include:

- Diffusion Pumps: These have no moving parts and use jets of hot oil vapor to capture gas molecules and push them out. They are robust and can achieve very deep vacuums (e.g., 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁷ Torr).

- Turbomolecular Pumps: These use a series of high-speed spinning rotor blades to mechanically push gas molecules toward the exhaust. They provide a very clean, oil-free vacuum.

Stage 4: The Holding Pump

A smaller holding pump is often included in the system. Its role is to maintain the vacuum on certain components, like the diffusion pump, during idle periods. This prevents oil vapor from migrating back into the main chamber and ensures the high-vacuum pump is ready for the next cycle.

Understanding the Trade-offs: Pump Selection and System Design

The choice and configuration of pumps in a vacuum system is a critical design decision based on balancing performance, cost, and process requirements. There is no single "best" setup.

Mechanical Pumps: The Workhorse with Limitations

Mechanical pumps are essential but can only achieve a rough vacuum. For processes that only require degassing or simple annealing, this may be sufficient. They are the simplest and most cost-effective component.

Diffusion Pumps: High Vacuum at a Cost

Diffusion pumps are a time-tested solution for achieving high vacuum. Their main trade-off is the use of oil, which carries a small but non-zero risk of backstreaming—where oil vapor contaminates the furnace chamber. Modern baffles and traps greatly minimize this risk.

Turbomolecular Pumps: Clean but Complex

Turbomolecular pumps provide an exceptionally clean, hydrocarbon-free vacuum, which is critical for sensitive electronics or medical applications. However, they are mechanically complex, have high-speed moving parts, are more expensive, and can be sensitive to sudden bursts of pressure.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The pumping system configuration must be matched directly to the metallurgical process you intend to run.

- If your primary focus is simple annealing or degassing (soft vacuum): A system with only a mechanical pump is often sufficient and cost-effective.

- If your primary focus is high-purity brazing or sintering (high vacuum): A multi-stage system with a mechanical pump and a diffusion or turbomolecular pump is essential to prevent contamination.

- If your primary focus is rapid cycle times in a production environment: Adding a roots booster pump can significantly reduce the time needed to reach the target vacuum level, increasing throughput.

Understanding this staged operation empowers you to control your furnace environment with precision, ensuring repeatable and high-quality results.

Summary Table:

| Stage | Pump Type | Function | Pressure Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mechanical (Roughing) Pump | Removes bulk air from chamber | ~760 to 10⁻² Torr |

| 2 | Booster Pump (Optional) | Speeds up pumpdown, moves large gas volumes | Bridges rough to high vacuum |

| 3 | High-Vacuum Pump (e.g., Diffusion, Turbomolecular) | Achieves deep vacuum for sensitive processes | 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁷ Torr |

| 4 | Holding Pump | Maintains vacuum on components during idle periods | Varies based on system |

Optimize your laboratory's high-temperature processes with KINTEK's advanced vacuum furnace solutions! Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse labs with reliable high-temperature furnace systems, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures precise alignment with your unique experimental needs, delivering contamination-free environments for brazing, sintering, and more. Contact us today to discuss how our tailored solutions can enhance your process integrity and efficiency!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press Tube Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the purpose of performing medium vacuum annealing on working ampoules? Ensure Pure High-Temp Diffusion

- What is the purpose of setting a mid-temperature dwell stage? Eliminate Defects in Vacuum Sintering

- Why is a high-vacuum environment necessary for sintering Cu/Ti3SiC2/C/MWCNTs composites? Achieve Material Purity

- What processing conditions does a vacuum furnace provide for TiCp/Fe microspheres? Sintering at 900 °C

- What is the function of a vacuum sintering furnace in the SAGBD process? Optimize Magnetic Coercivity and Performance