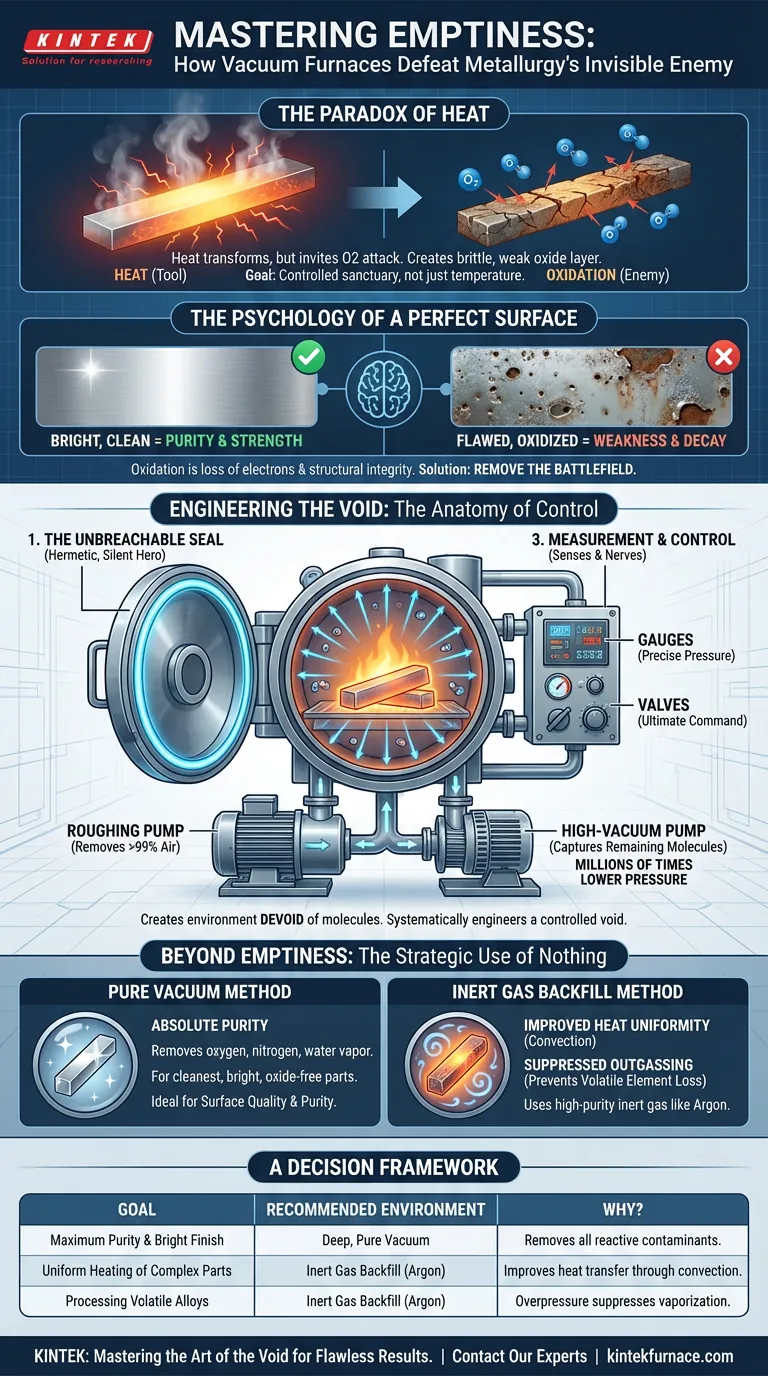

The Paradox of Heat

Heat is the primary tool of the metallurgist. It grants us the power to soften, shape, and transform materials. Yet, it also invites an invisible enemy to the feast: oxidation.

In the open air, applying intense heat is like opening a door for oxygen to aggressively attack a material's surface. This reaction isn't just a cosmetic tarnish; it's a fundamental compromise. It creates a brittle, weak oxide layer that can lead to catastrophic failure down the line.

The challenge, then, isn't merely about reaching a target temperature. It's about creating a controlled sanctuary where heat can do its work without inviting destruction.

The Psychology of a Perfect Surface

We are psychologically wired to see a bright, clean surface as a sign of purity and strength. A flawed, oxidized surface signals weakness and decay. This instinct is scientifically sound.

Oxidation is a process of loss—the material loses electrons, and with them, its structural integrity. At the molecular level, it's a form of corrosion accelerated by heat. Preventing it is non-negotiable for creating reliable, high-performance components.

The solution is not to fight the oxygen. It is to remove the battlefield entirely.

Engineering the Void: The Anatomy of Control

A vacuum furnace achieves this by creating an environment so devoid of molecules that oxidation becomes a physical impossibility. This is not about "filtering out" oxygen; it's about systematically engineering a controlled void.

This feat of environmental control relies on a triad of critical systems working in perfect concert.

1. The Unbreachable Seal

Before a single molecule can be removed, the chamber must be hermetically sealed. A high-integrity seal, using robust flanges and gaskets, is the silent hero of the process. Without it, the most powerful pump is merely fighting a losing battle against the entire atmosphere.

2. The Mechanical Heart: The Pump System

The vacuum pump is the engine that creates the void. Industrial systems typically use a two-stage approach:

- Roughing Pumps: These do the initial heavy lifting, removing over 99% of the air from the chamber.

- High-Vacuum Pumps: A turbomolecular or diffusion pump then takes over, capturing the remaining stray molecules to achieve pressures millions of times lower than our atmosphere.

This system doesn't just lower the oxygen concentration; it starves the environment of nearly all gas molecules, leaving nothing behind to react with the hot material.

3. The Senses and Nerves: Measurement and Control

A void you cannot measure is a void you cannot control.

- Gauges act as the system's senses, providing precise pressure readings that tell the operator the quality of the vacuum.

- Valves are the nerves, allowing for the isolation of the chamber and the controlled flow of gases, giving the engineer ultimate command over the internal environment.

Beyond Emptiness: The Strategic Use of Nothing

While a deep vacuum offers the purest environment, sometimes a strategic alternative is required. The choice depends entirely on the desired outcome for the material.

The Pure Vacuum Method

This is the path to absolute purity. By removing virtually all contaminants—oxygen, nitrogen, water vapor—a deep vacuum allows for the creation of exceptionally clean, bright, and oxide-free parts. It is the ideal choice when surface quality and material purity are the highest priorities.

The Inert Gas Backfill Method

Sometimes, a complete void is not the optimal thermal environment. In this technique, the chamber is first evacuated and then intentionally backfilled with a high-purity inert gas like argon or nitrogen. This offers two key advantages:

- Improved Heat Uniformity: The gas provides a medium for convection, transferring heat more evenly to complex parts compared to the pure radiation of a vacuum.

- Suppressed Outgassing: The positive pressure of the inert gas can prevent volatile elements within an alloy (like zinc in brass) from "boiling off" at high temperatures and low pressures.

A Decision Framework

Choosing the right atmospheric condition is critical for success. Your goal determines the strategy.

| Goal | Recommended Environment | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Purity & Bright Finish | Deep, Pure Vacuum | Removes all reactive contaminants for the cleanest possible surface. |

| Uniform Heating of Complex Parts | Inert Gas Backfill (Argon) | The gas improves heat transfer through convection, ensuring even temperature distribution. |

| Processing Volatile Alloys | Inert Gas Backfill (Argon) | The overpressure suppresses the vaporization of low-boiling-point elements from the alloy. |

True mastery in material science comes from controlling not just temperature, but the very atmosphere in which your process takes place. At KINTEK, we specialize in building the systems that give you this precise control. Our range of customizable Muffle, Tube, Vacuum, and CVD furnaces are designed to create the perfect, repeatable environment for your most demanding applications.

To achieve flawless, oxidation-free results in your laboratory or production line, you need a partner who understands the art of mastering the void. Contact Our Experts

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1400℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace Molybdenum Wire Vacuum Sintering Furnace

Related Articles

- The Alchemy of Isolation: Why Tube Furnaces Are Indispensable for Innovation

- From Powder to Power: The Physics of Control in a Tube Furnace

- The Invisible Contaminant: Why Your Furnace Atmosphere is Sabotaging Your Results

- The Controlled Universe: Mastering Matter Inside a 70mm Tube Furnace

- Beyond Heat: The Unseen Power of Environmental Control in Tube Furnaces