In essence, Joule heating is the direct conversion of electrical energy into thermal energy. This occurs whenever an electric current flows through a conductor that has electrical resistance. In an induction furnace, this principle is the final, critical step that generates the immense heat required to melt metals, converting the energy from internally-induced "eddy currents" into thermal energy.

The core concept of an induction furnace is to use a magnetic field to turn the metal itself into its own heating element. This is accomplished by inducing electrical currents within the metal, which then generate intense heat through the fundamental principle of Joule heating.

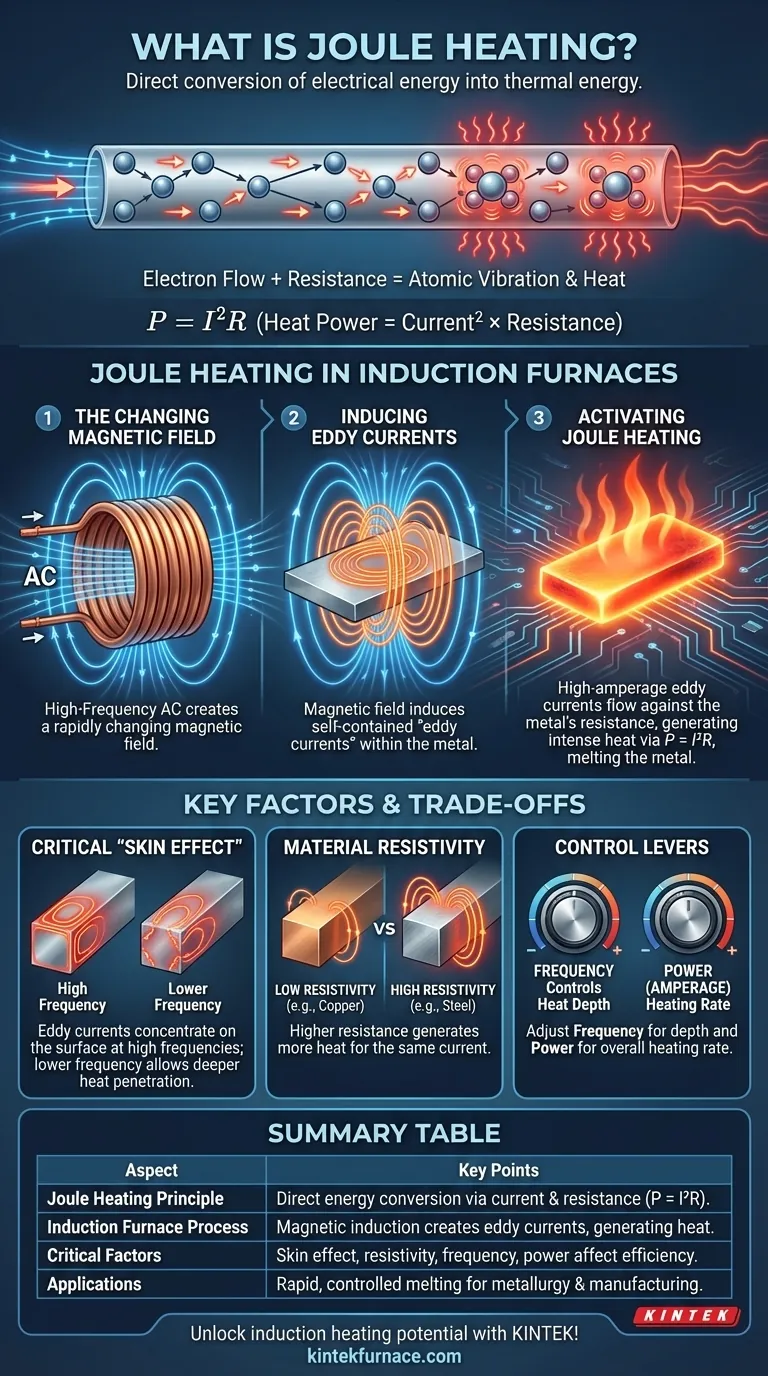

The Fundamental Principle: What is Joule Heating?

Joule heating, also known as resistive or ohmic heating, is one of the most fundamental principles in electrical physics. It describes a predictable and quantifiable relationship between electricity and heat.

From Electron Flow to Atomic Vibration

At a microscopic level, an electrical current is the flow of electrons through a material. As these electrons move, they collide with the atoms and ions that make up the conductor's structure.

Each collision transfers kinetic energy from the electron to the atom, causing the atom to vibrate more intensely. This increased atomic vibration is what we perceive and measure as an increase in temperature, or heat.

The Role of Electrical Resistance

Electrical resistance (R) is the property of a material that impedes the flow of electric current. It is this very "opposition" that causes the energy transfer.

A perfect conductor with zero resistance would generate no Joule heat. Conversely, materials with higher resistance will generate more heat for the same amount of electrical current, as more energy is lost by the electrons during their journey.

The Governing Equation: P = I²R

The relationship is precisely defined by Joule's First Law, where the heat generated (P, for power) is proportional to the square of the current (I) multiplied by the resistance (R).

This formula reveals a crucial insight: doubling the current quadruples the heat output. This is why inducing very high currents is the key to the rapid and intense heating seen in industrial applications.

How Induction Furnaces Exploit Joule Heating

An induction furnace is a masterful application of physics. It doesn't use an external flame or heating element to melt the metal. Instead, it cleverly uses electromagnetism to trigger Joule heating directly within the target material.

Step 1: The Changing Magnetic Field

The process begins with a large, water-cooled copper coil. A high-frequency alternating current (AC) is passed through this coil.

According to Faraday's Law of Induction, this AC current generates a powerful and rapidly changing magnetic field in the space within and around the coil.

Step 2: Inducing Eddy Currents

The conductive material to be melted (the "charge") is placed inside this magnetic field. The fluctuating magnetic field lines pass through the metal, inducing small, circular loops of electrical current within it.

These self-contained, internal currents are known as eddy currents. The furnace has effectively created electricity inside the metal without any physical contact.

Step 3: Activating Joule Heating

Now, the final step occurs. These high-amperage eddy currents flow through the metal, which has its own inherent electrical resistance.

As dictated by the P = I²R principle, the flow of these eddy currents against the metal's resistance generates tremendous amounts of heat. This is Joule heating in action, melting the metal from the inside out.

Understanding the Key Factors and Trade-offs

The efficiency of an induction furnace is not automatic. It depends on a careful balance of electrical and material properties.

The Critical "Skin Effect"

At the high frequencies used in induction heating, eddy currents do not flow uniformly through the material. They tend to concentrate in a thin layer near the surface, a phenomenon known as the skin effect.

This can be an advantage, allowing for rapid surface heating. However, the frequency must be selected carefully based on the material and the size of the part to ensure the heat penetrates deeply enough for a thorough melt.

The Impact of Material Resistivity

The R in P = I²R is the material's own electrical resistivity. A material with extremely low resistance (like pure copper) can be more difficult to heat with induction because it allows eddy currents to flow too easily, generating less friction and thus less heat.

Conversely, metals with higher resistivity (like steel) heat up very effectively. This is a critical consideration when designing an induction process for a specific alloy.

Frequency and Power as Control Levers

The two primary variables an operator can control are the frequency of the AC current and the power (amperage) supplied to the coil.

Adjusting frequency controls the depth of heat penetration (due to the skin effect), while adjusting power controls the overall heating rate by increasing the magnitude of the induced eddy currents.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Understanding this two-step process—magnetic induction followed by Joule heating—is key to controlling the outcome.

- If your primary focus is process efficiency: Concentrate on optimizing the frequency and coil geometry to maximize the strength of induced eddy currents and leverage the skin effect for your specific material and part size.

- If your primary focus is material selection: Recognize that a material's electrical resistivity and magnetic permeability directly impact how effectively it can be heated via induction; not all conductive metals are equally suitable.

- If your primary focus is fundamental understanding: Remember the core mechanism: An external magnetic field induces internal eddy currents, and those currents generate heat through the material's own resistance via Joule's First Law.

By mastering these principles, you can move from simply observing the process to intelligently controlling and engineering it for any application.

Summary Table:

| Aspect | Key Points |

|---|---|

| Joule Heating Principle | Direct conversion of electrical energy to heat via current flow in resistive materials; governed by P = I²R. |

| Induction Furnace Process | Uses magnetic fields to induce eddy currents in metal, generating heat through Joule heating for melting. |

| Critical Factors | Skin effect, material resistivity, frequency, and power control heating efficiency and penetration depth. |

| Applications | Ideal for rapid, controlled metal melting in industries like metallurgy and manufacturing. |

Unlock the full potential of induction heating with KINTEK! Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with advanced high-temperature furnace solutions, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we precisely meet your unique experimental requirements for efficient metal melting and processing. Contact us today to discuss how our tailored solutions can enhance your lab's performance and productivity!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Induction Melting Furnace

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 1400℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz and Alumina Tube

People Also Ask

- How has vacuum smelting impacted the development of superalloys? Unlock Higher Strength and Purity

- How does the Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM) process work? Achieve Superior Metal Purity and Control

- What is the purpose of vacuum melting, casting and re-melting equipment? Achieve High-Purity Metals for Critical Applications

- What are some common applications of vacuum induction melting and casting (VIM&C)? Essential for Aerospace, Medical, and Nuclear Industries

- What is vacuum induction melting technology and why is it important? Achieve High-Purity Metals for Critical Applications