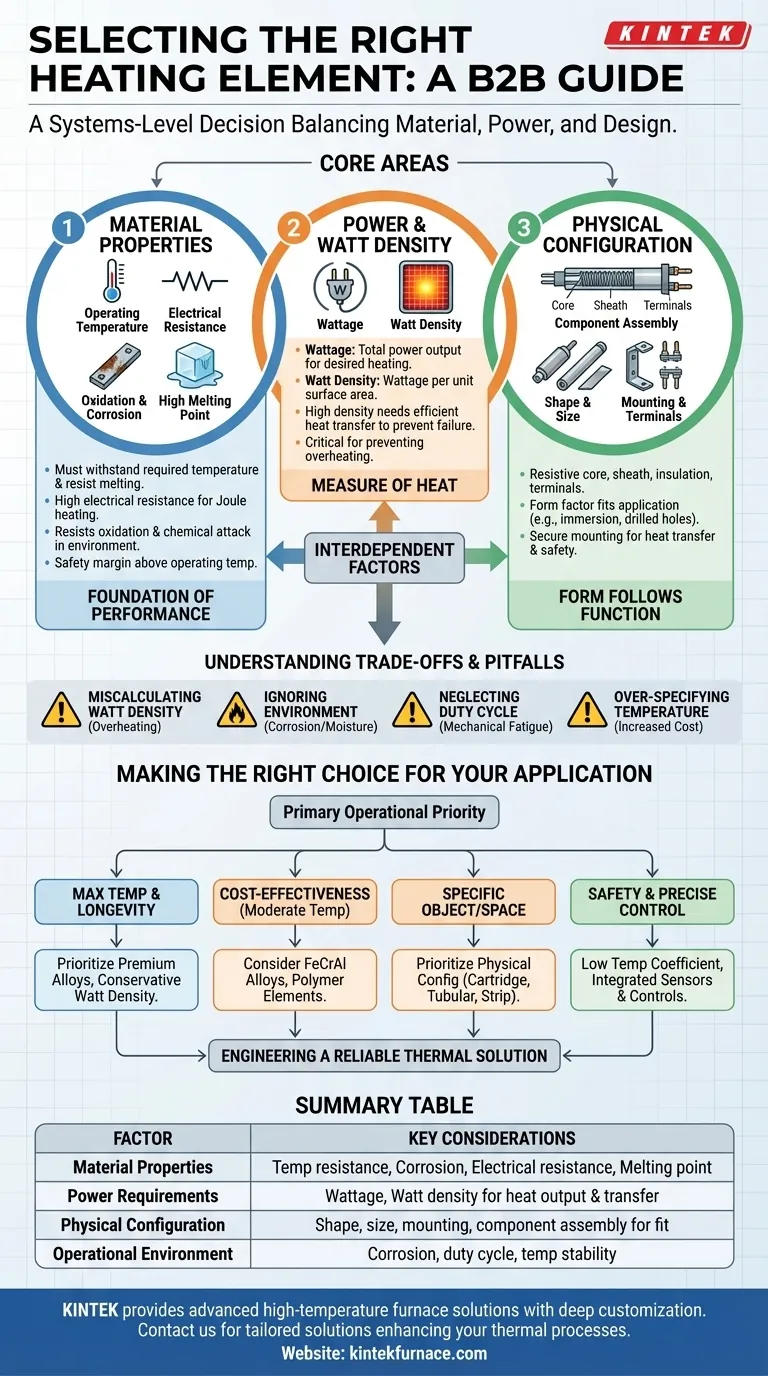

To select the correct heating element, you must evaluate three core areas: the material's properties (like temperature and corrosion resistance), the power requirements (wattage and watt density), and the physical design or configuration (its shape, size, and how it mounts). These factors are interdependent and must be matched precisely to your application's environment and performance goals. A mismatch in any area can lead to premature failure or inefficient performance.

Choosing a heating element is not just about meeting a target temperature. It is a systems-level decision that balances material science, electrical engineering, and physical constraints to ensure safety, efficiency, and operational longevity.

Deconstructing the Core Factors

To make an informed decision, you must understand how each primary factor influences the element's behavior and suitability for your specific task. These are not isolated variables; they work together as a complete system.

Material Selection: The Foundation of Performance

The material of the resistive core is the heart of the heating element. Its properties dictate the operational limits and lifespan.

- Operating Temperature: The material must withstand the required temperature without melting or degrading. Nickel-chromium (Nichrome) alloys are excellent for high temperatures, while others like polymer PTC materials are suited for lower, self-regulating applications.

- Electrical Resistance: The material must have high electrical resistance to generate heat effectively through Joule heating, but not so high that it acts as an insulator. This property should also be stable across the temperature range.

- Oxidation and Corrosion Resistance: At high temperatures, materials react with the atmosphere. The element must resist oxidation to prevent burnout. In chemical or liquid heating, it must also resist corrosion from the specific medium.

- High Melting Point: A high melting point is critical. It provides a safety margin and ensures the element remains solid and stable well above its maximum operating temperature.

Power and Watt Density: The Measure of Heat

Power determines how much heat is produced, while watt density determines how intensely that heat is transferred.

- Wattage: This is the total power output of the element, measured in watts. It must be sufficient to overcome heat loss and raise the temperature of the target substance or space in the desired time.

- Watt Density: This is the wattage per unit of surface area (e.g., watts per square inch). It is a critical, often overlooked metric. A high watt density can cause the element to overheat and fail prematurely if the surrounding medium cannot absorb heat fast enough.

Physical Configuration: Form Follows Function

A heating element is more than just the resistive wire; it is a complete assembly designed for a specific purpose.

- Component Assembly: An element consists of the resistive core, protective sheath material, electrical insulation (often magnesium oxide powder for thermal conductivity), and terminals for power connection.

- Shape and Size: The form factor must match the application. Cartridge heaters fit into drilled holes, tubular heaters are used for immersion in liquids, and flexible or strip heaters wrap around surfaces.

- Mounting and Terminals: The element must be securely mounted to ensure proper heat transfer and safety. The electrical leads and connectors must also be appropriate for the voltage, current, and environment.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Common Pitfalls

Selecting an element based on a single factor without considering the others is a common cause of failure. Understanding the trade-offs is key to engineering a reliable system.

Miscalculating Watt Density

This is the most common pitfall. An element with a watt density that is too high for the application (e.g., heating air instead of water) will quickly burn out. Water can pull heat away much faster than air, allowing for a higher watt density.

Ignoring the Operating Environment

A heating element that performs perfectly in dry air may fail in days if exposed to a corrosive atmosphere or intermittent moisture. The sheath material and end seals are just as critical as the core alloy.

Neglecting the Duty Cycle

The frequency of operation matters. An element used intermittently undergoes repeated thermal expansion and contraction, which can cause mechanical fatigue. A continuous-duty element may face different challenges, like creep deformation at high temperatures.

Over-specifying for Temperature

Choosing an exotic, high-temperature alloy when a standard one will suffice significantly increases cost. Always match the material's capability to the actual, not theoretical, maximum operating temperature.

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Your final decision should be guided by your primary operational priority.

- If your primary focus is maximum temperature and longevity: Prioritize premium alloys like nickel-chromium and ensure the watt density is conservative for the medium being heated.

- If your primary focus is cost-effectiveness for a moderate-temperature task: Consider iron-chromium-aluminum (FeCrAl) alloys or even specialized polymer elements if self-regulation is beneficial.

- If your primary focus is heating a specific object or space: Prioritize the physical configuration (cartridge, tubular, strip, flexible) to ensure optimal heat transfer and physical fit.

- If your primary focus is safety and precise control: Look for elements with a low temperature coefficient of resistance and consider integrating external sensors and controls.

By systematically evaluating these factors, you move from simply buying a part to engineering a reliable and efficient thermal solution.

Summary Table:

| Factor | Key Considerations |

|---|---|

| Material Properties | Temperature resistance, corrosion resistance, electrical resistance, melting point |

| Power Requirements | Wattage, watt density for heat output and transfer |

| Physical Configuration | Shape, size, mounting, component assembly for application fit |

| Operational Environment | Corrosion, duty cycle, temperature stability to prevent failure |

Struggling to select the right heating element for your lab? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnace solutions, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. With strong deep customization capabilities, we precisely meet your unique experimental requirements for safety, efficiency, and longevity. Contact us today to discuss how our tailored solutions can enhance your thermal processes!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Disilicide MoSi2 Thermal Heating Elements for Electric Furnace

- Silicon Carbide SiC Thermal Heating Elements for Electric Furnace

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Split Multi Heating Zone Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

People Also Ask

- What ceramic materials are commonly used for heating elements? Discover the Best for Your High-Temp Needs

- What are the advantages of using molybdenum-disilicide heating elements for aluminum alloy processing? (Rapid Heating Guide)

- What are the primary applications of Molybdenum Disilicide (MoSi2) heating elements in furnaces? Achieve High-Temp Excellence

- What is the temperature range for MoSi2 heating elements? Maximize Lifespan in High-Temp Applications

- How can high temperature heating elements be customized for different applications? Tailor Elements for Peak Performance