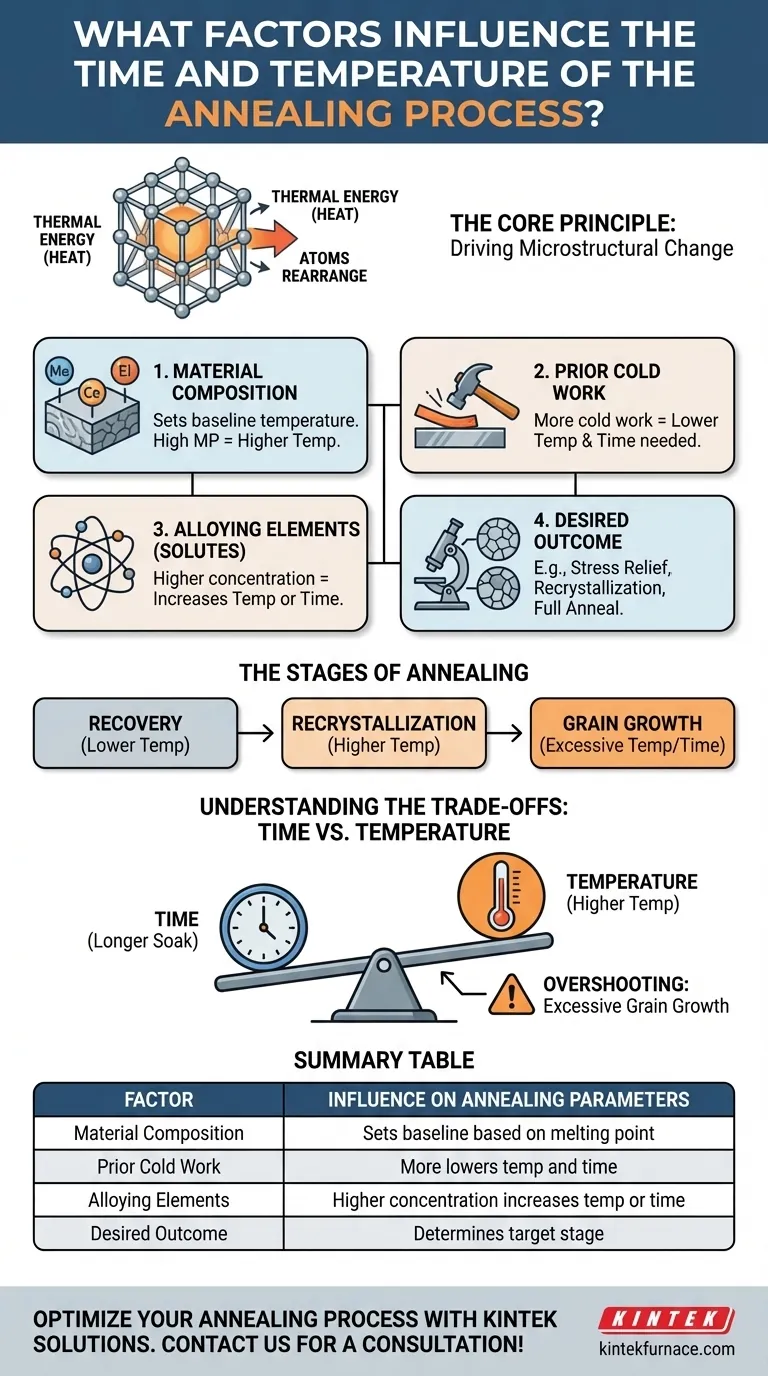

The time and temperature for any annealing process are a function of four key variables. These are the material's composition, the amount of prior cold work it has undergone, the concentration of alloying elements (solutes), and the specific microstructural outcome you intend to achieve with the heat treatment.

Annealing is not a fixed recipe; it is a controlled process of providing just enough thermal energy for a specific duration to drive a desired change in a material's microstructure. The "correct" parameters are the minimum required to achieve your goal without causing undesirable side effects like excessive grain growth.

The Core Principle: Driving Microstructural Change

Annealing is a heat treatment process used to alter the physical and sometimes chemical properties of a material. The goal is to make it more ductile and less hard, making it easier to work with.

Thermal Energy as the Catalyst

At its core, annealing works by providing thermal energy (heat). This energy allows the atoms within the material's crystal lattice to move and rearrange themselves into a more stable, lower-energy state.

Temperature determines the rate at which atoms can move, while time determines how long they have to complete their journey.

The Stages of Annealing

As temperature and time increase, a cold-worked material typically passes through three stages:

- Recovery: At lower temperatures, internal stresses are relieved, but the grain structure is largely unchanged.

- Recrystallization: New, strain-free grains begin to form and grow, replacing the deformed grains created by cold work. This is where ductility is restored.

- Grain Growth: If the temperature is too high or held for too long, the new, strain-free grains will continue to grow larger.

Deconstructing the Key Factors

Each variable influences how much thermal energy is needed to trigger these microstructural changes.

The Material Itself (Composition)

A material's fundamental composition and melting point set the baseline for its annealing temperature. A high-melting-point material like steel requires a significantly higher annealing temperature than a low-melting-point material like aluminum.

The Degree of Prior Cold Work

Cold working (such as rolling, drawing, or bending) deforms the material's crystal structure, introducing defects called dislocations. This process stores a significant amount of internal energy within the material.

The more stored energy from cold work, the lower the temperature and shorter the time needed to initiate recrystallization. The material is already "primed" and eager to release that energy.

The Role of Solute Concentration (Alloying Elements)

Alloying elements or impurities (solutes) within a metal's crystal structure act as obstacles. They can "pin" the boundaries of grains, making it harder for them to move or for new grains to form.

Therefore, a higher concentration of solutes increases the required temperature or time for annealing. More energy is needed to overcome this "solute drag" effect.

The Desired Annealing Outcome

The specific goal of the treatment is perhaps the most important factor, as it dictates which stage of annealing you are targeting.

- Stress Relief: Requires the lowest temperature. The goal is only to achieve recovery, relieving internal stresses from processes like welding without significantly changing the grain structure or hardness.

- Recrystallization: Requires a higher temperature. The goal is to form a completely new set of strain-free grains, fully restoring the ductility lost during cold work.

- Full Anneal / Spheroidization: Often requires even higher temperatures or complex heating/cooling cycles. These processes are designed to achieve maximum softness, typically by changing the shape and distribution of secondary phases within the microstructure (e.g., forming rounded spheroids from cementite plates in steel).

Understanding the Trade-offs: Time vs. Temperature

The relationship between time and temperature is not independent; they are inversely related.

The Interchangeable Nature of Time and Temp

You can often achieve the same degree of annealing by using a higher temperature for a shorter time, or a lower temperature for a longer time. The total thermal energy input is what matters.

The Danger of "Overshooting": Excessive Grain Growth

The most common pitfall is applying too much heat or holding it for too long. While a higher temperature speeds up the process, it dramatically increases the risk of excessive grain growth.

Large grains can reduce a material's strength, fracture toughness, and can lead to a poor surface finish known as "orange peel" on subsequent forming operations.

Economic and Practical Constraints

From a production standpoint, shorter cycle times are almost always preferred. This creates a practical push towards using the highest possible temperature that can be precisely controlled without overshooting into the grain growth regime. Long soaks at lower temperatures are effective but more expensive in terms of energy and furnace time.

Setting Your Annealing Parameters

To select the right parameters, you must first define your primary objective.

- If your primary focus is restoring ductility after cold work: Aim for the recrystallization temperature, ensuring you achieve a fine, new grain structure without significant growth.

- If your primary focus is relieving internal stress from welding or machining: Use a lower-temperature stress relief anneal that doesn't fundamentally alter the core strength and grain structure.

- If your primary focus is achieving maximum softness and machinability: A full anneal or spheroidizing cycle is required, which involves higher temperatures or specific thermal profiles.

- If your primary focus is production efficiency: You may favor a higher temperature for a shorter duration, but this demands precise process control to avoid property degradation.

Ultimately, the ideal annealing process is a deliberate balance between these factors to achieve your target properties with precision and efficiency.

Summary Table:

| Factor | Influence on Annealing Parameters |

|---|---|

| Material Composition | Sets baseline temperature based on melting point |

| Prior Cold Work | More cold work lowers temperature and time needed |

| Alloying Elements | Higher concentration increases temperature or time |

| Desired Outcome | Determines target stage (e.g., stress relief, recrystallization) |

Struggling to optimize your annealing process? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnace solutions tailored to your needs. Our product line—including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems—is enhanced by strong deep customization capabilities to precisely meet unique experimental requirements. Achieve superior material properties with our expertise—contact us today for a consultation!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the primary function of a muffle furnace for BaTiO3? Master High-Temp Calcination for Ceramic Synthesis

- What is the role of a muffle furnace in the synthesis of water-soluble Sr3Al2O6? Precision in SAO Production

- What substances are prohibited from being introduced into the furnace chamber? Prevent Catastrophic Failure

- Why is a high-performance muffle furnace required for the calcination of nanopowders? Achieve Pure Nanocrystals

- What environmental conditions are critical for SiOC ceramicization? Master Precise Oxidation & Thermal Control