While a vacuum is essential for many high-temperature processes, relying on it exclusively introduces a distinct set of operational challenges that are often misunderstood. The primary difficulties are not with creating the vacuum itself, but with managing its consequences, including increased equipment maintenance, the risk of process contamination from outgassing, extremely limited cooling control, and unusual material reactions like sublimation or cold welding.

A vacuum is not an empty, passive space; it is an active environment with its own physical rules. True success in vacuum furnace applications comes from mastering the consequences of removing the atmosphere, particularly the loss of convection for heat transfer and the release of trapped contaminants.

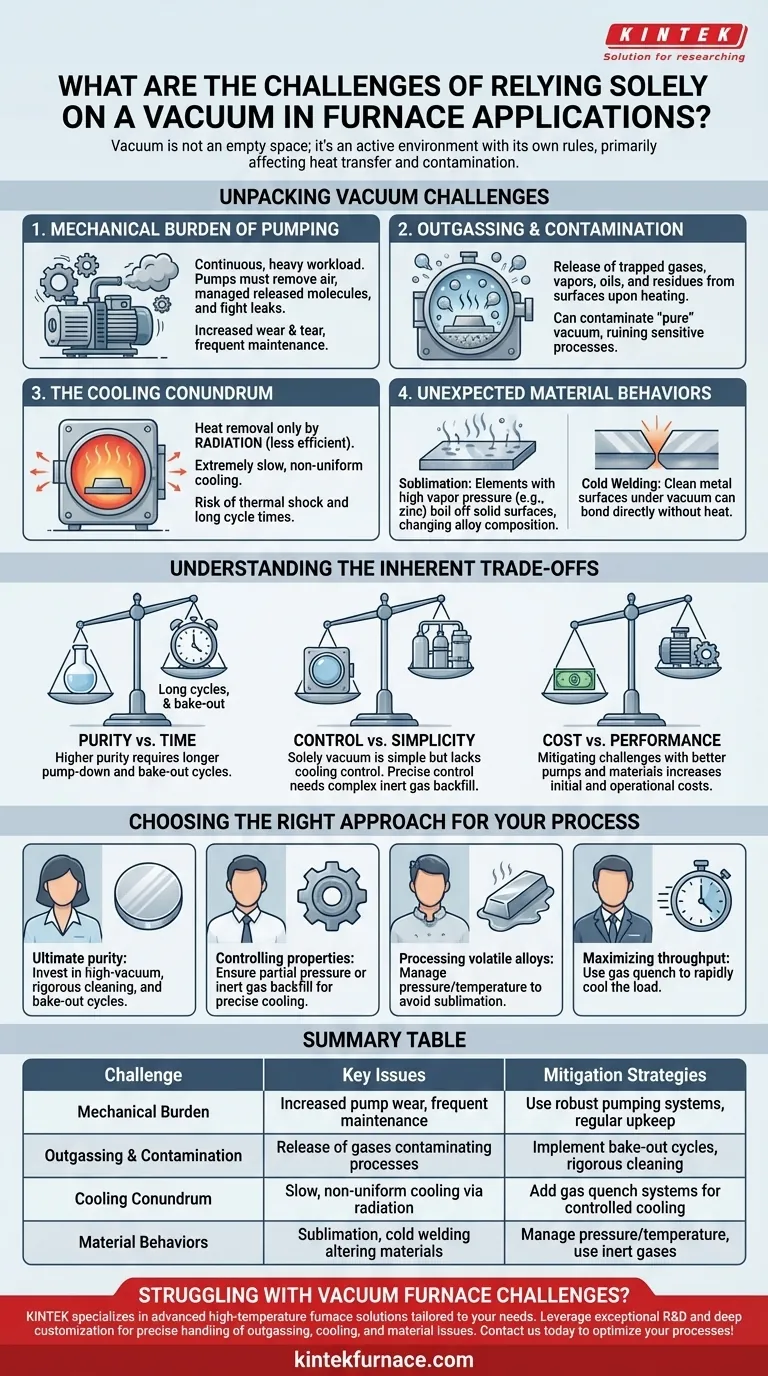

The Myth of "Empty" Space: Unpacking Vacuum Challenges

A vacuum fundamentally changes how energy and matter behave within a furnace. Understanding these changes is critical to anticipating and mitigating the problems that can arise during a process cycle.

Challenge 1: The Mechanical Burden of Pumping

Operating a vacuum furnace places a continuous, heavy workload on its pumping system. This is not a "set it and forget it" operation.

Pumps must work constantly not only to remove air at the start but also to manage molecules released during the heating process and to fight any microscopic leaks in the system. This sustained effort leads to increased wear and tear on mechanical pumps, more frequent oil changes, and a higher overall maintenance burden compared to atmosphere furnaces.

Challenge 2: Outgassing and Contamination

One of the most persistent challenges is outgassing, the release of trapped gases and vapors from the surfaces within the furnace.

As the chamber is heated under vacuum, molecules of water, oils, and other residues adsorbed on the chamber walls, fixtures, and even the workpiece itself are boiled off. These released molecules can contaminate the supposedly "pure" vacuum environment, potentially ruining sensitive processes like brazing or medical implant manufacturing.

Challenge 3: The Cooling Conundrum

In a standard furnace, heat is primarily removed by convection, where a gas like air or nitrogen physically carries thermal energy away from the part. In a vacuum, there are almost no gas particles to facilitate this transfer.

Heat can only escape via radiation, which is significantly less efficient, especially at lower temperatures. This results in extremely slow and often non-uniform cooling, dramatically increasing cycle times and creating the risk of thermal shock if not properly managed.

Challenge 4: Unexpected Material Behaviors

The absence of atmospheric pressure can cause materials to behave in non-intuitive ways. Two key examples are sublimation and cold welding.

Sublimation is when an element turns directly from a solid to a gas. In a vacuum, the boiling point of many materials is lowered. Elements with high vapor pressure, like zinc in brass or cadmium, can literally boil off the surface of an alloy at processing temperatures, changing its composition and properties.

Cold welding can occur when two exceptionally clean metal surfaces make contact in a high vacuum. With no air or oxide layer to keep them separate, the atoms of the two pieces can bond directly, fusing them together without any applied heat.

Understanding the Inherent Trade-offs

Choosing to use a vacuum is a decision that involves balancing competing priorities. These trade-offs define the reality of operating a vacuum furnace.

Purity vs. Time

Achieving a higher, purer vacuum level requires more time. Longer pump-down cycles are needed to remove more molecules, and pre-heating "bake-out" cycles are often necessary to force outgassing to occur before the actual process begins. This pursuit of purity directly extends the total cycle time.

Control vs. Simplicity

Relying solely on vacuum for cooling is simple but offers almost no control over the cooling rate. To gain precise control—essential for most metallurgical processes—you must add complexity. This involves backfilling the chamber with an inert gas like argon or nitrogen to enable controlled convective cooling, often called a "gas quench."

Cost vs. Performance

Mitigating the challenges of vacuum comes at a price. High-performance, low-outgassing chamber materials, more powerful and cleaner pumping systems (like turbo or cryopumps), and sophisticated gas backfill systems all improve performance but significantly increase the furnace's initial and operational costs.

Choosing the Right Approach for Your Process

The ideal strategy depends entirely on the goal of your specific application. By understanding the challenges, you can select the right configuration and operational procedures.

- If your primary focus is ultimate purity for sensitive parts: Invest in high-vacuum systems, rigorous cleaning protocols, and bake-out cycles to aggressively combat outgassing.

- If your primary focus is controlling metallurgical properties: Ensure your furnace has a partial pressure or inert gas backfill capability for precise control over cooling rates.

- If your primary focus is processing alloys with volatile elements: Carefully manage pressure and temperature profiles to stay below the sublimation threshold of critical elements.

- If your primary focus is maximizing throughput: Optimize your cycle by using a gas quench to rapidly cool the load, as this is often the longest phase of a pure vacuum cycle.

Understanding these vacuum-specific behaviors transforms them from unavoidable problems into solvable engineering parameters for your process.

Summary Table:

| Challenge | Key Issues | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Burden | Increased pump wear, frequent maintenance | Use robust pumping systems, regular upkeep |

| Outgassing & Contamination | Release of gases contaminating processes | Implement bake-out cycles, rigorous cleaning |

| Cooling Conundrum | Slow, non-uniform cooling via radiation | Add gas quench systems for controlled cooling |

| Material Behaviors | Sublimation, cold welding altering materials | Manage pressure/temperature, use inert gases |

Struggling with vacuum furnace challenges in your lab? KINTEK specializes in advanced high-temperature furnace solutions tailored to your needs. Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we offer Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our deep customization capabilities ensure precise handling of outgassing, cooling control, and material issues, enhancing purity, efficiency, and throughput for diverse laboratory applications. Contact us today to optimize your processes and achieve superior results!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press Tube Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the vacuum heat treatment process? Achieve Superior Surface Quality and Material Performance

- Why does heating steel rod bundles in a vacuum furnace eliminate heat transfer paths? Enhance Surface Integrity Today

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- What are the benefits of vacuum heat treatment? Achieve Superior Metallurgical Control