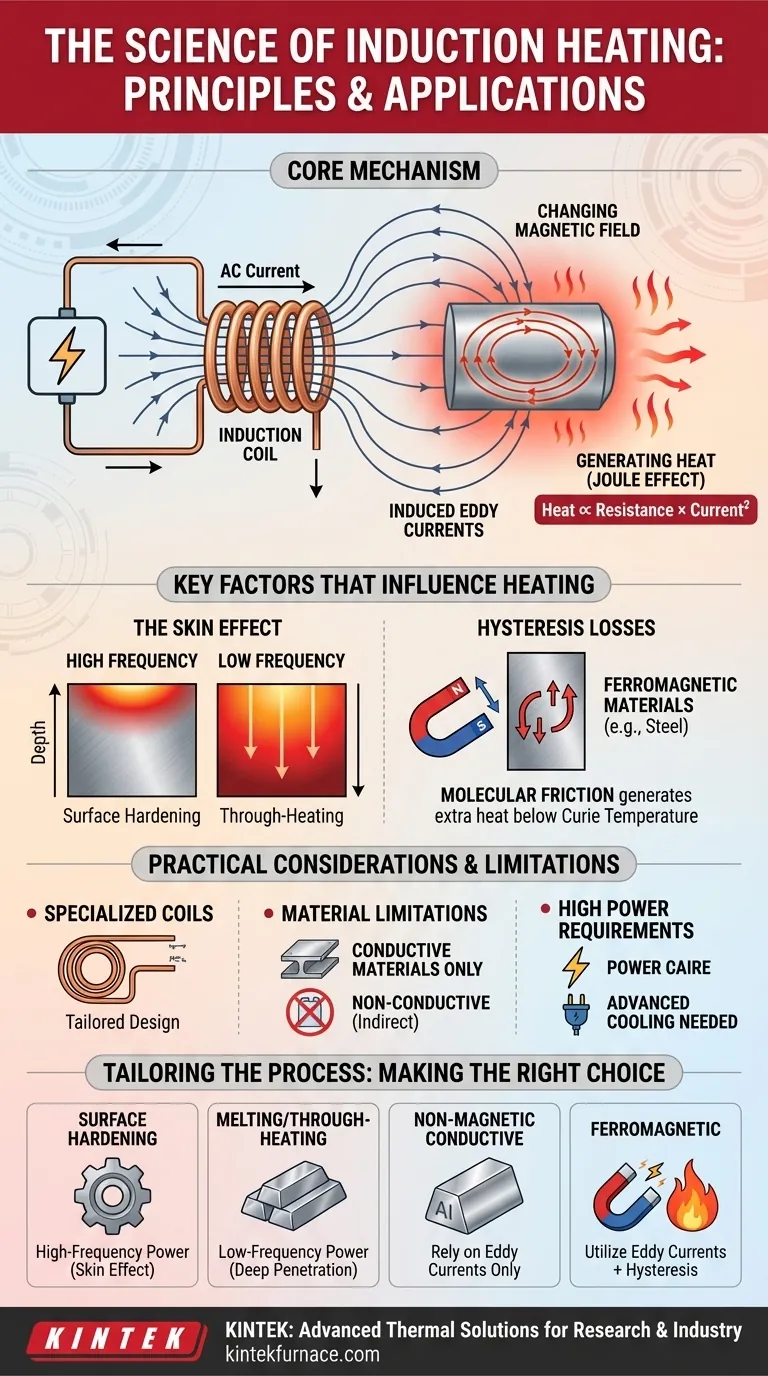

At its most fundamental level, induction heating requires only two things to occur: a changing magnetic field and an electrically conductive material placed within that field. The interaction between these two elements is what generates heat directly inside the material without any physical contact from the heat source.

While the basic requirements are simple, the effectiveness of induction heating depends on a precise understanding of the underlying physics. It is not just about having the two components, but about controlling the interplay between the magnetic field's frequency and the target material's properties.

The Core Mechanism: How Induction Generates Heat

To understand induction heating, we must look at the sequence of physical phenomena that convert electrical energy into thermal energy inside a workpiece.

Principle 1: Creating a Changing Magnetic Field

The process begins with an induction coil, typically made of copper tubing through which coolant flows. A high-frequency alternating current (AC) is passed through this coil.

This AC current creates a powerful and rapidly changing magnetic field in the space around and within the coil, as described by Faraday's Law of Induction.

Principle 2: Inducing Eddy Currents

When an electrically conductive workpiece is placed inside this magnetic field, the field induces circulating electrical currents within the material. These are known as eddy currents.

These eddy currents mirror the alternating pattern of the current in the coil, flowing in closed loops within the workpiece.

Principle 3: Generating Heat (The Joule Effect)

The workpiece's material has a natural electrical resistance. As the induced eddy currents flow against this resistance, they generate intense heat.

This phenomenon is known as the Joule effect. The heat produced is proportional to the material's resistance and the square of the current, turning the workpiece into its own heat source.

Key Factors That Influence Heating

The two basic requirements are just the starting point. Several other factors determine how and where the material heats up, which is critical for practical applications.

The Skin Effect: Heating from the Outside In

The induced eddy currents do not flow uniformly through the material. At high frequencies, they tend to concentrate near the surface of the workpiece. This is known as the skin effect.

This principle is crucial for applications like surface hardening, where you want to heat only the outer layer of a metal part without affecting its core. Lower frequencies allow the heat to penetrate deeper.

Hysteresis Losses: A Bonus for Magnetic Materials

For ferromagnetic materials like iron, steel, and nickel, a secondary heating mechanism occurs. The rapid reversals of the magnetic field cause friction at a molecular level as the material's magnetic domains resist changing direction.

This internal friction, called hysteresis loss, generates additional heat. This effect disappears once the material is heated past its Curie temperature and loses its magnetic properties.

Material Properties Matter

The efficiency of induction heating is directly tied to the workpiece's properties. Materials with high electrical resistance will heat up more quickly from the Joule effect.

Likewise, materials with high magnetic permeability will experience significant heating from hysteresis losses, adding to the overall effect.

Understanding the Practical Trade-offs

While powerful, induction heating is not a universal solution. It comes with specific engineering requirements and limitations that must be considered.

The Need for Specialized Coils

The induction coil, or inductor, is not a one-size-fits-all component. Its shape, size, and number of turns must be carefully designed to create the precise magnetic field required for a specific part and application.

Designing and manufacturing these coils can be complex and expensive, representing a significant part of the system's cost.

Material Limitations

The most obvious limitation is that induction heating works directly only on electrically conductive materials.

While non-conductive materials like plastics or ceramics can sometimes be heated indirectly by using a conductive "susceptor" that gets hot and transfers heat, the process is not designed for them.

High Power Requirements

Generating a powerful, high-frequency magnetic field requires a specialized AC power supply. The high currents flowing through the small copper coils also generate immense heat in the coil itself, necessitating advanced cooling systems to prevent it from melting.

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Understanding these principles allows you to tailor the induction process to a specific industrial or scientific goal.

- If your primary focus is surface hardening: Use a high-frequency power supply to leverage the skin effect, concentrating heat on the outer layer of the part.

- If your primary focus is melting or through-heating a large part: Use a lower frequency to ensure the magnetic field and resulting heat penetrate deep into the material's core.

- If your primary focus is heating a non-magnetic but conductive material (like aluminum or copper): You must rely entirely on powerful eddy currents for heating, as hysteresis losses will not contribute.

- If your primary focus is heating a ferromagnetic material below its Curie point: You can benefit from the combined effect of eddy currents and hysteresis, often making the process more efficient.

By controlling the field and understanding the material, you can turn a simple physical principle into a precise and powerful manufacturing tool.

Summary Table:

| Principle | Key Factor | Effect on Heating |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Changing Magnetic Field & Conductive Material | Generates internal heat via eddy currents (Joule Effect) |

| Heating Depth | Frequency of AC Current (Skin Effect) | High frequency heats surface; low frequency heats core |

| Material Impact | Electrical Resistivity & Magnetic Properties | Ferromagnetic materials gain extra heat from hysteresis losses |

| Practical Limitation | Material Conductivity | Only directly heats electrically conductive materials |

Ready to Harness the Power of Precision Induction Heating?

Understanding the theory is the first step. Implementing it effectively in your lab or production line requires robust, reliable equipment tailored to your specific materials and thermal processing goals—whether it's surface hardening, melting, or through-heating.

KINTEK delivers advanced thermal solutions built on deep expertise.

Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with advanced high-temperature furnace solutions. Our product line, including Muffle, Tube, and Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems, is complemented by our strong deep customization capability to precisely meet unique experimental requirements.

Let us help you turn this powerful principle into your competitive advantage.

Contact KINTEL today to discuss how our customized induction heating systems can solve your specific challenges.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Silicon Carbide SiC Thermal Heating Elements for Electric Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- RF PECVD System Radio Frequency Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- Why is silicon carbide resistant to chemical reactions in industrial furnaces? Unlock Durable High-Temp Solutions

- Why are SIC heating elements resistant to chemical corrosion? Discover the Self-Protecting Mechanism

- What are the properties and capabilities of Silicon Carbide (SiC) as a heating element? Unlock Extreme Heat and Durability

- What makes SIC heating elements superior for high-temperature applications? Unlock Efficiency and Durability

- What are the advantages of using high purity green silicon carbide powder in heating elements? Boost Efficiency and Lifespan