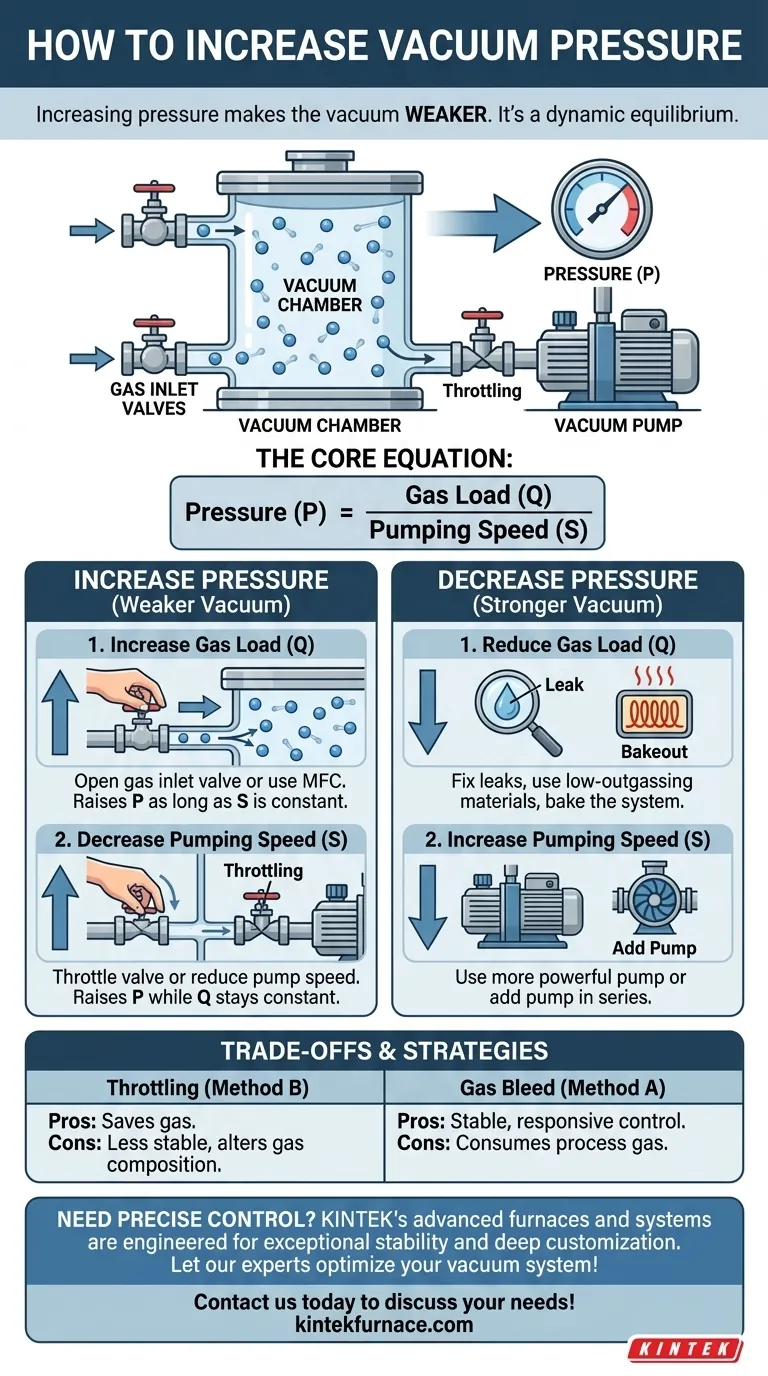

To increase the pressure in a vacuum system—meaning to make the vacuum weaker—you must either introduce more gas or reduce the system's pumping speed. This is typically done by opening a controlled gas inlet valve or by partially closing a valve between the chamber and the pump. The term "increasing vacuum" can be ambiguous, as a higher quality vacuum is defined by a lower absolute pressure.

The pressure inside any vacuum chamber is a dynamic equilibrium between the rate of gas removal (pumping speed) and the rate of gas entering the system (gas load). To change the pressure, you must intentionally alter one side of this fundamental balance.

What Does "Vacuum Pressure" Truly Mean?

Before adjusting pressure, it's critical to understand the terminology. In vacuum science, "high vacuum" and "low pressure" are synonymous.

The Inverse Relationship

Think of pressure as the density of gas molecules in a space. A high vacuum (like in outer space) has very few gas molecules and therefore a very low pressure. A low vacuum (like that from a household vacuum cleaner) has many more gas molecules and a relatively high pressure.

When you "increase the vacuum," you are decreasing the number of molecules and thus lowering the pressure reading. When you "increase the pressure," you are adding molecules and lowering the quality of the vacuum.

The Core Equation of Vacuum

The stable pressure (P) in your system is determined by the total gas load (Q) divided by the effective pumping speed (S).

Pressure (P) = Gas Load (Q) / Pumping Speed (S)

Every method for changing pressure involves manipulating either Q or S.

How to Increase Pressure (Achieve a Lower Vacuum)

This is the most direct interpretation of your question. The goal here is to raise the pressure reading in your chamber, for example, to a specific setpoint for a manufacturing process.

Method 1: Increase the Gas Load (Q)

The most common and controllable method is to intentionally introduce gas into the chamber. This is often called "backfilling" or using a "gas bleed."

By adding gas, you increase the Q term in the equation, which directly raises P as long as the pumping speed S remains constant. This is typically achieved with a precision needle valve or a mass flow controller (MFC) for highly accurate and repeatable results.

Method 2: Decrease the Pumping Speed (S)

You can also raise the pressure by reducing the pump's effectiveness. This is known as "throttling."

Reducing S while Q (from leaks and outgassing) stays constant will cause P to rise. This is done by partially closing a large valve (like a gate or butterfly valve) between the chamber and the pump or, less commonly, by reducing the pump's motor speed with a variable frequency drive (VFD).

How to Decrease Pressure (Achieve a Higher Vacuum)

This is the opposite goal, but it's often what users mean when they want a "better" vacuum. The objective is to lower the pressure reading as much as possible.

Method 1: Reduce the Gas Load (Q)

For high and ultra-high vacuum, minimizing the gas load is the most critical factor. This is a battle against all unwanted sources of gas molecules.

Key sources to address include:

- Real Leaks: Finding and fixing any physical leaks that allow atmospheric gas into the system.

- Outgassing: Gas molecules desorbing from the chamber's internal surfaces and any materials inside. This is managed by choosing low-outgassing materials (like stainless steel instead of plastic) and by "baking" the system (heating it to accelerate gas release).

- Permeation: Gas diffusing through the solid materials of the chamber itself, especially through elastomer seals like O-rings.

Method 2: Increase the Pumping Speed (S)

Using a more powerful pump or adding pumps will increase S and therefore lower P. This could mean upgrading from a small roughing pump to a larger one or adding a high-vacuum pump (like a turbomolecular or cryogenic pump) in series with your roughing pump to reach lower pressure ranges.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing a method for pressure control depends on your specific goals and involves important trade-offs.

Throttling vs. Gas Bleed

For maintaining a specific process pressure, throttling saves on gas consumption but can be less stable and may alter the gas composition if the pump removes different gases at different rates. A gas bleed provides very stable, responsive control but constantly consumes your process gas, which can be expensive.

The Cost of Higher Vacuum

Achieving progressively lower pressures (higher vacuums) becomes exponentially more difficult and expensive. Moving from low to high vacuum requires different pumps, gauges, and building practices. Moving to ultra-high vacuum (UHV) requires specialized materials, all-metal seals, and mandatory system bakeouts.

System Equilibrium

Remember that a vacuum system is never static. Pressure is a result of equilibrium. When you make an adjustment—like opening a gas valve—the pressure will change and then settle at a new, stable level where the gas load and pumping speed are once again in balance.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your strategy for pressure control should be dictated by your ultimate objective.

- If your primary focus is precise process control (e.g., for coating or etching): Use a closed-loop system with a mass flow controller to bleed in gas and a high-quality gauge to maintain a constant pressure.

- If your primary focus is reaching the lowest possible pressure: Your effort should be on minimizing the gas load by finding leaks, using clean, low-outgassing materials, and baking the system.

- If your primary focus is simple, coarse pressure adjustment: Manually throttling a main valve or using a simple needle valve to admit air are straightforward and effective methods.

Ultimately, mastering vacuum pressure comes from understanding and controlling the balance between gas entering and gas leaving your system.

Summary Table:

| Goal | Method | Key Action |

|---|---|---|

| Increase Pressure (Weaker Vacuum) | Increase Gas Load (Q) | Open a gas inlet valve (e.g., needle valve, MFC) to introduce gas. |

| Decrease Pumping Speed (S) | Partially close a valve (throttle) between the chamber and the pump. | |

| Decrease Pressure (Stronger Vacuum) | Decrease Gas Load (Q) | Fix leaks, use low-outgassing materials, and bake the system. |

| Increase Pumping Speed (S) | Use a more powerful pump or add a high-vacuum pump in series. |

Need precise and reliable control over your vacuum processes? KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnaces, including our Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces and CVD/PECVD Systems, are engineered for exceptional stability and control. Leveraging our strong in-house R&D and manufacturing capabilities, we provide deep customization to perfectly match your unique experimental or production requirements. Let our experts help you optimize your vacuum system—contact us today to discuss your specific needs!

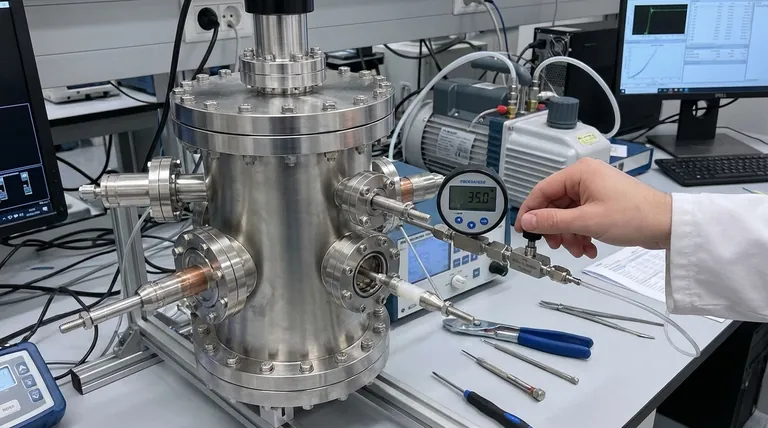

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Ultra Vacuum Electrode Feedthrough Connector Flange Power Lead for High Precision Applications

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

- 304 316 Stainless Steel High Vacuum Ball Stop Valve for Vacuum Systems

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- How does a vacuum pumping system contribute to the fabrication of high-quality silicide structures? Ensure Material Purity

- Why is a high vacuum system critical for sealing the quartz tube used in Fe3GeTe2 single crystal preparation?

- What design considerations are important for custom vacuum chambers? Optimize for Performance, Cost, and Application Needs

- What are the main technical requirements for vacuum pumps in vacuum sintering furnaces? Ensure Material Purity and Efficiency

- How does a high-vacuum pump system facilitate the synthesis of high-quality calcium-based perrhenates? Expert Synthesis