In a vacuum furnace, the vacuum level is measured as a residual pressure, not an absence of matter. This pressure is represented in units like Pascals (Pa), Torr (equivalent to mmHg), or millitorr (mTorr), with lower numerical values indicating a deeper, higher-quality vacuum. The measurement is performed by specialized vacuum gauges integrated into a system of pumps and valves designed to remove atmospheric gases.

Measuring vacuum is fundamentally about verifying the purity of the furnace environment. The goal is to confirm the removal of reactive gases, primarily oxygen, to prevent unwanted chemical reactions like oxidation during high-temperature processing.

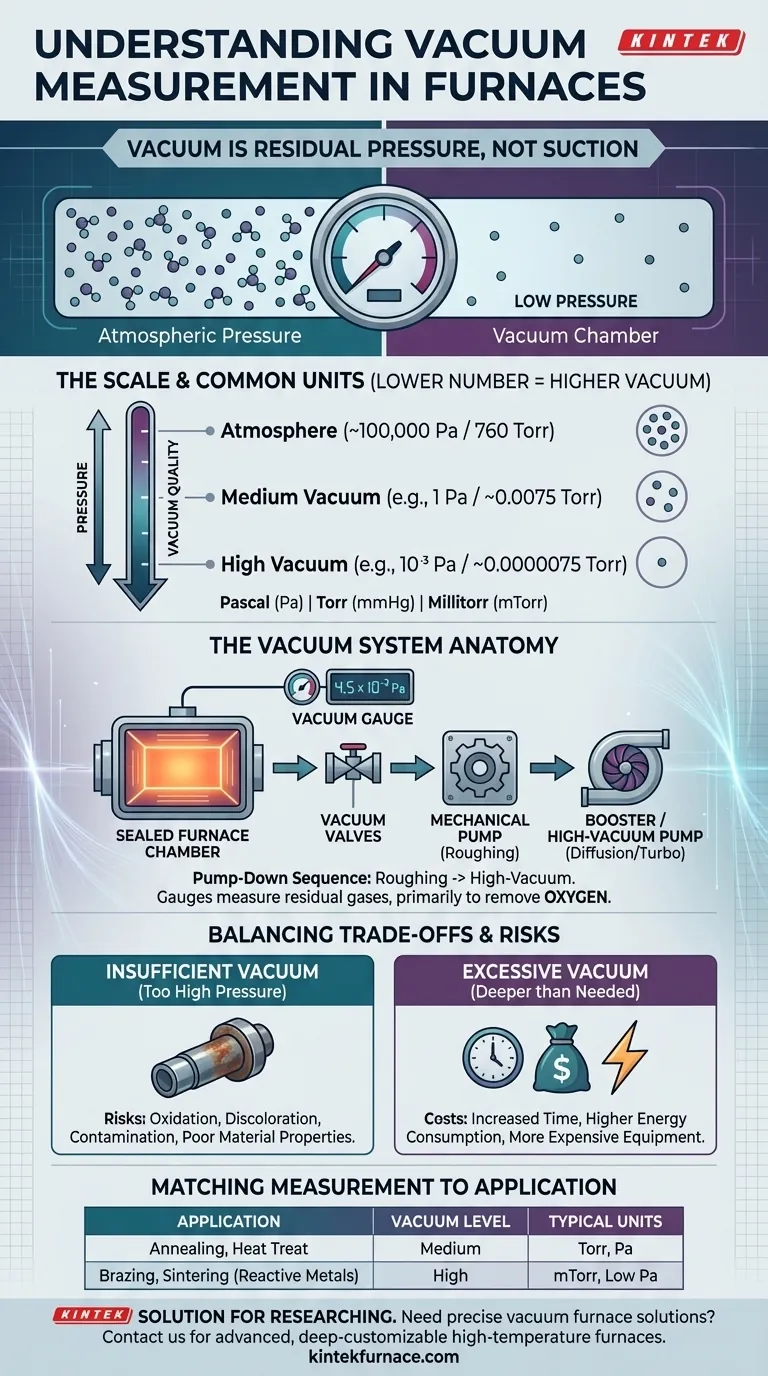

Understanding Vacuum as Pressure

A common misconception is that vacuum is a force of "suction." In reality, it is a condition of extremely low pressure relative to the standard atmosphere around us.

The Scale of Vacuum

When evaluating a vacuum, a lower pressure reading signifies a higher-quality vacuum. This can feel counter-intuitive. For example, a pressure of 1 Pa is a much deeper vacuum than a pressure of 100 Pa because there are far fewer gas molecules remaining in the chamber.

Common Units of Measurement

Different units are used depending on the industry and the level of vacuum required.

- Pascal (Pa): The standard SI unit for pressure. High-vacuum applications often use millipascals (mPa) or micro-pascals (µPa). A typical maximum vacuum level might be around 7×10⁻³ Pa.

- Torr (mmHg): An older unit, defined as 1/760th of a standard atmosphere. It is roughly equivalent to the pressure exerted by a one-millimeter column of mercury (mmHg).

- Millitorr (mTorr): Simply one-thousandth of a Torr. This unit is frequently used for medium and high-vacuum processes where fine resolution is needed.

The Anatomy of a Vacuum System

The measurement device is just one part of a larger, integrated system designed to create and maintain the required vacuum level. The quality of the final measurement depends on the performance of the entire system.

Creating the Vacuum: The Pump-Down Sequence

A vacuum is achieved using a series of pumps. A single pump is rarely sufficient for high-vacuum applications.

- Mechanical Pumps (Roughing Pumps): These pumps do the initial work, removing the vast majority of air from the sealed furnace chamber to create a "rough" vacuum.

- Booster & High-Vacuum Pumps: Once the mechanical pump reaches its limit, a secondary pump takes over. This can be a Roots pump (booster), diffusion pump, or turbo-molecular pump, each designed to operate efficiently at lower pressures to achieve the final high vacuum level.

Measuring the Vacuum: The Role of Gauges

A vacuum measuring device, or gauge, is the sensor that provides the pressure reading. No single gauge can cover the entire pressure range from atmosphere down to high vacuum. Therefore, furnaces often use multiple gauges optimized for different pressure regimes.

Maintaining the Vacuum: Valves and Seals

The system relies on an airtight seal to prevent atmospheric gases from leaking back into the chamber. Vacuum valves are used to isolate different parts of the system, such as separating the furnace chamber from the pumps once the target vacuum is reached. The measurement confirms both the pump performance and the integrity of these seals.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Achieving the deepest possible vacuum is not always the best or most efficient strategy. The target vacuum level is a critical process parameter that involves balancing cost, time, and metallurgical requirements.

The Risk of Insufficient Vacuum

If the vacuum level is too low (i.e., the pressure is too high), residual oxygen will remain in the chamber. During heating, this oxygen can react with the part's surface, causing oxidation, discoloration, or contamination, which can compromise the material's properties and surface finish.

The Cost of Excessive Vacuum

Pulling a deeper vacuum than necessary increases operational costs. It requires more time for the pumps to work, consumes more energy, and necessitates more complex and expensive equipment (like diffusion or turbo-molecular pumps). The goal is to match the vacuum level precisely to the needs of the process.

Matching the Measurement to Your Goal

The required vacuum level is dictated by the material being processed and the desired outcome. Your choice of measurement unit often reflects the sensitivity of your application.

- If your primary focus is general heat treating or annealing: A medium vacuum is often sufficient to prevent heavy oxidation. Measurements in Torr or a higher range of Pascals are typically adequate.

- If your primary focus is high-purity brazing, sintering, or processing reactive metals: A high vacuum is non-negotiable to prevent even trace amounts of contamination. Measurements will be in mTorr or low-range Pascals (e.g., 10⁻³ Pa).

Ultimately, measuring vacuum is about controlling the furnace environment to guarantee the quality and integrity of your final product.

Summary Table:

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Measurement Units | Pascals (Pa), Torr, Millitorr (mTorr) |

| Key Gauges | Multiple types for different pressure ranges |

| Pump Types | Mechanical (roughing), Booster, High-vacuum (e.g., turbo-molecular) |

| Importance | Prevents oxidation, controls contamination, ensures process quality |

| Typical Applications | Medium vacuum for annealing; high vacuum for brazing/sintering |

Need precise vacuum furnace solutions for your lab? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnaces like Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. With strong deep customization capabilities, we tailor solutions to meet your unique experimental needs—ensuring optimal vacuum control, efficiency, and material integrity. Contact us today to discuss how we can enhance your processes!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press Tube Furnace

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- Vacuum Sealed Continuous Working Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the primary components of a vacuum hot press furnace? Master the Core Systems for Precise Material Processing

- What is a vacuum hot press furnace? Unlock Superior Material Performance

- How does precise temperature control affect Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Master Titanium Hot Pressing Accuracy

- What are the overall benefits of using hot pressing in manufacturing? Achieve Superior Performance and Precision

- Which process parameters must be optimized for specific materials in a vacuum hot press furnace? Achieve Optimal Density and Microstructure