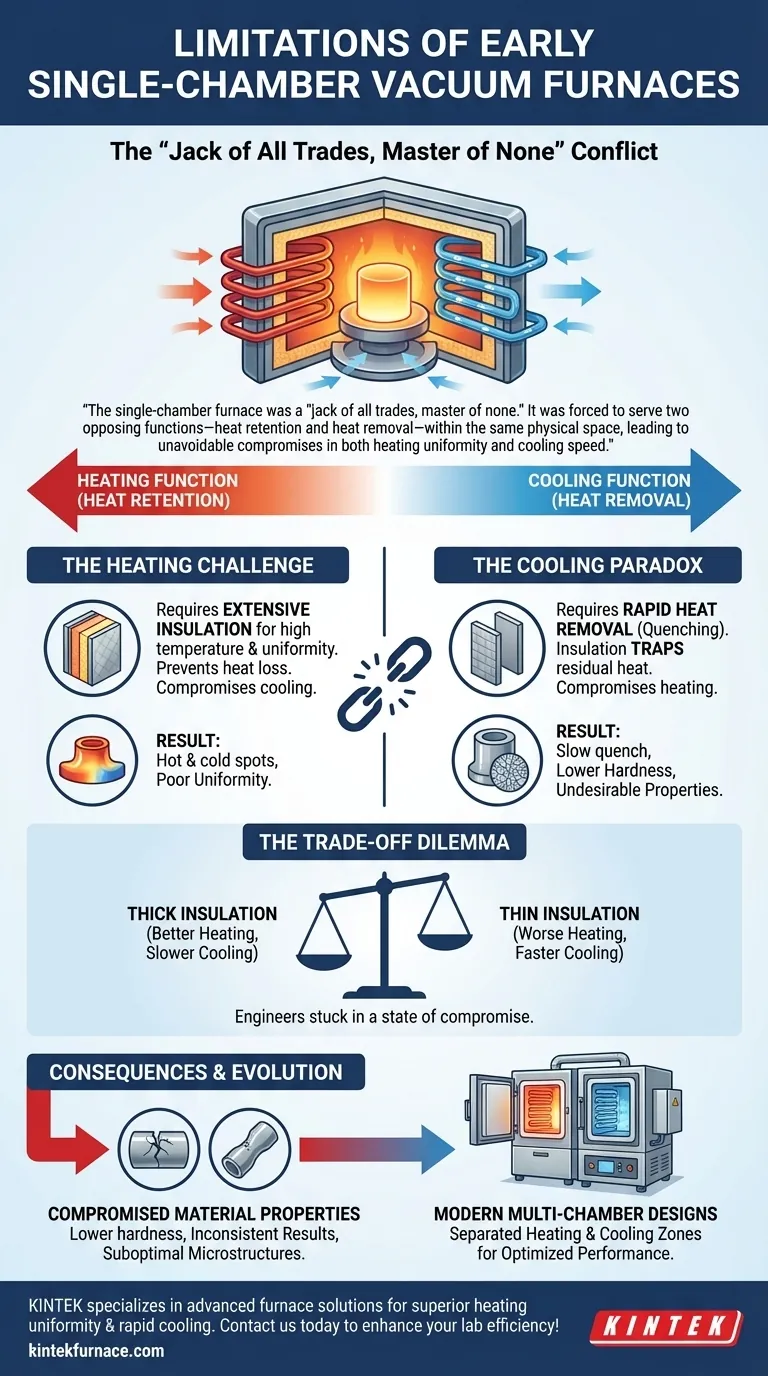

At their core, the primary limitation of early single-chamber vacuum furnace designs was a fundamental and unavoidable conflict between their heating and cooling functions. Because a single chamber was responsible for both creating intense, uniform heat and then allowing for rapid cooling, any design choice that optimized one process inherently compromised the other. This created a ceiling on performance and material quality.

The single-chamber furnace was a "jack of all trades, master of none." It was forced to serve two opposing functions—heat retention and heat removal—within the same physical space, leading to unavoidable compromises in both heating uniformity and cooling speed.

The Core Conflict: Heating vs. Cooling

The central challenge stemmed from the laws of thermodynamics. A chamber designed to hold heat efficiently is, by definition, poor at releasing it quickly.

The Challenge of Effective Heating

Early designs struggled to achieve and maintain uniform temperatures. The primary goal during the heating cycle is to transfer energy to the workload evenly and with minimal loss.

To do this effectively, the chamber required extensive insulation. This hot zone insulation was critical for reaching high temperatures and ensuring that all parts of the workload heated at the same rate, preventing hot and cold spots.

The Paradox of Efficient Cooling

The goal of the cooling cycle, or "quenching," is the exact opposite: to remove heat from the workload as rapidly as possible to lock in desired material properties like hardness.

However, the very insulation that was so beneficial for heating now became a major obstacle. It trapped residual heat within the furnace walls and structure, slowing down the entire cooling process and making a rapid, effective quench nearly impossible.

Consequence: Compromised Material Properties

This inherent conflict meant that metallurgical outcomes were often suboptimal. A slow quench can result in lower hardness, undesirable microstructures, and inconsistent properties across a batch of parts.

Engineers were perpetually stuck in a state of compromise, unable to achieve both a perfectly uniform heat-up and a sufficiently rapid cool-down.

Understanding the Trade-offs

This central conflict forced designers and operators to make difficult choices that directly impacted the quality of the final product.

The Insulation Dilemma

The most significant trade-off was insulation. Using thick, high-efficiency insulation would improve temperature uniformity and energy efficiency during heating. However, it would dramatically slow the cooling rate.

Conversely, using thinner insulation or less of it would allow the furnace to cool faster, but at the cost of poor heating uniformity and higher energy consumption. This often led to inconsistent results.

The Uniformity Problem

Beyond the insulation issue, early heating element designs and chamber geometries often created uneven heat distribution. References to "simple burning and fire at the elbow of each pipeline" in even more primitive ovens highlight the long-standing challenge of delivering heat evenly.

Even in more advanced convective designs, achieving true temperature uniformity across a large workload in a single, compromised chamber was a persistent engineering hurdle.

Understanding the Evolutionary Path

These limitations were not just minor inconveniences; they were the primary drivers инновации for the next generation of furnace technology. Understanding this context clarifies why furnace design evolved.

- If your primary focus is high-performance heat treatment (e.g., aerospace, medical): The compromises 결혼 in single-chamber designs were unacceptable, driving the development of multi-chamber furnaces where heating and cooling are physically separate and individually optimized.

- If your primary focus was simple, non-critical processes (e.g., basic annealing): An early single-chamber design might have been sufficient, but it could never deliver the precision and repeatability required by modern standards.

Overcoming these foundational limitations is what ultimately led to the sophisticated, multi-chamber vacuum furnaces used in critical industries today.

Summary Table:

| Limitation | Impact |

|---|---|

| Heating vs. Cooling Conflict | Compromised performance and material quality |

| Insulation Dilemma | Poor temperature uniformity or slow cooling rates |

| Uniformity Problem | Inconsistent heat distribution and suboptimal results |

| Compromised Material Properties | Lower hardness and undesirable microstructures |

Are you facing challenges with furnace performance in your lab? KINTEK specializes in advanced high-temperature furnace solutions, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. With exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we offer deep customization to precisely meet your unique experimental needs, ensuring superior heating uniformity and rapid cooling for optimal material outcomes. Contact us today to enhance your laboratory efficiency and achieve consistent, high-quality results!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in LP-DED? Optimize Alloy Integrity Today

- What is the vacuum heat treatment process? Achieve Superior Surface Quality and Material Performance

- What are the proper procedures for handling the furnace door and samples in a vacuum furnace? Ensure Process Integrity & Safety

- What are the functions of a high-vacuum furnace for CoReCr alloys? Achieve Microstructural Precision and Phase Stability

- What are the benefits of vacuum heat treatment? Achieve Superior Metallurgical Control