In practice, heating elements are overwhelmingly made from metallic alloys, with the most common being Nichrome, an alloy of nickel and chromium. This material is chosen for its superior ability to generate heat and, critically, to withstand the destructive effects of high temperatures over long periods. Other materials like iron-chromium-aluminum alloys, refractory metals, and graphite are selected for more specialized industrial applications.

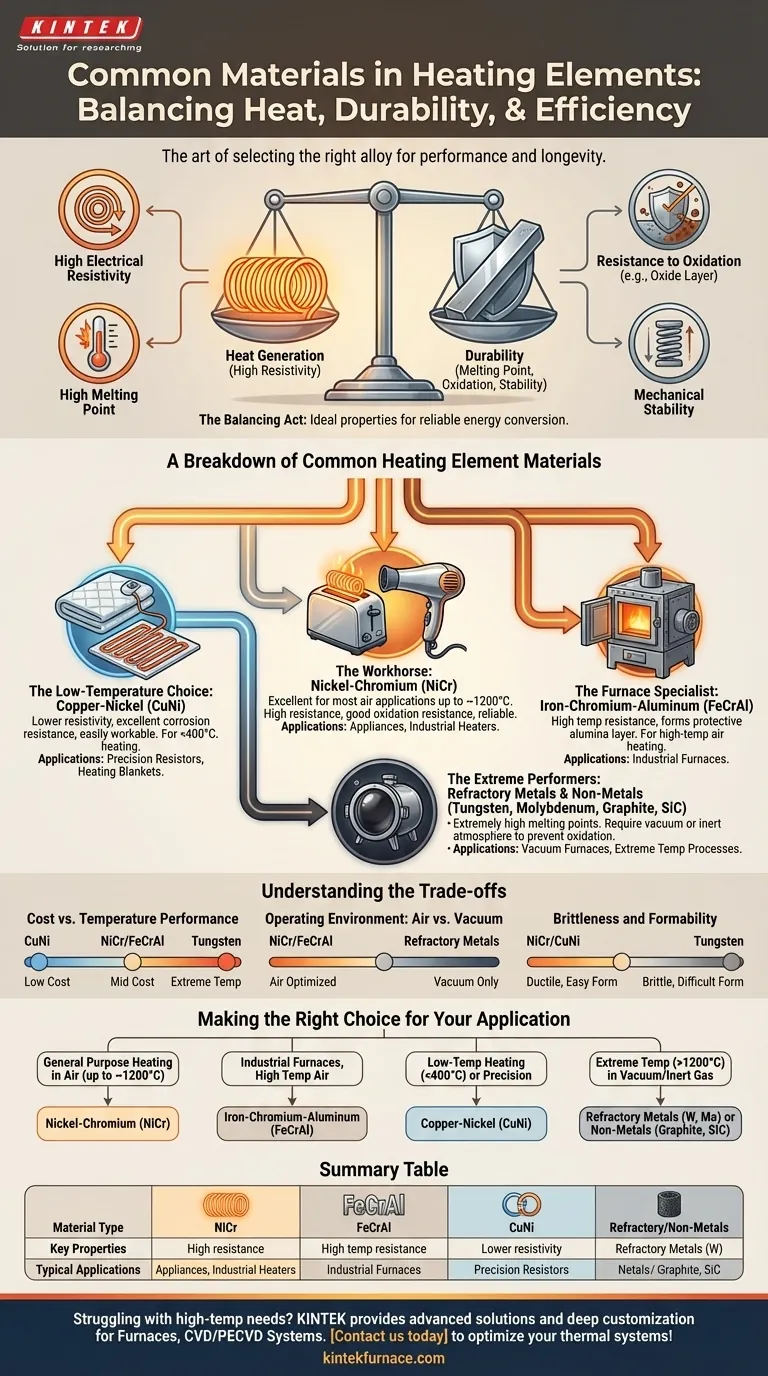

The selection of a heating element material is not just about its ability to get hot. It is fundamentally a balancing act between high electrical resistance (to generate heat efficiently) and robust durability (to resist oxidation and melting at operating temperatures).

The Core Properties of an Ideal Heating Element

To understand why certain materials are chosen, we must first define the ideal characteristics needed to convert electricity into heat reliably and repeatedly.

High Electrical Resistivity

A material with high electrical resistance is essential. According to Joule's law of heating, the heat produced is proportional to the resistance. High resistivity allows a shorter wire to generate the required amount of heat, making the element more compact and efficient.

High Melting Point

This is a non-negotiable requirement. The material must have a melting point significantly higher than its intended operating temperature to ensure it remains structurally sound and does not fail.

Resistance to Oxidation

When metals get hot in the presence of air, they oxidize (rust). A good heating element material, like Nichrome, forms a stable, protective outer layer of oxide (chromium oxide in this case). This layer prevents oxygen from reaching the underlying metal, dramatically extending the element's lifespan.

Mechanical Stability

The material should have minimal thermal expansion and contraction as it heats and cools. It must also maintain a relatively constant resistance across its operating temperature range to provide consistent and predictable heat output.

A Breakdown of Common Heating Element Materials

Different applications demand different balances of performance and cost, leading to the use of several key material families.

The Workhorse: Nickel-Chromium (NiCr) Alloys

Nichrome (typically 80% nickel, 20% chromium) is the go-to material for a vast range of applications, from toasters and hair dryers to industrial process heaters. Its combination of high resistance, excellent oxidation resistance, and good mechanical strength makes it a reliable default choice.

The Furnace Specialist: Iron-Chromium-Aluminum (FeCrAl) Alloys

FeCrAl alloys serve a similar purpose to NiCr but are often used in high-temperature industrial furnaces. They can sometimes reach higher temperatures than Nichrome and form a highly protective alumina (aluminum oxide) layer, offering exceptional durability in harsh environments.

The Low-Temperature Choice: Copper-Nickel (CuNi) Alloys

For applications that do not require intense heat, such as electric blankets, underfloor heating, and precision resistors, CuNi alloys are ideal. They have lower resistivity than NiCr but offer excellent corrosion resistance and are easily workable.

The Extreme Performers: Refractory Metals and Non-Metals

For the most demanding environments, such as vacuum furnaces operating at extreme temperatures, specialized materials are required.

- Refractory Metals: Tungsten and Molybdenum have exceptionally high melting points but will oxidize rapidly in air. They are reserved for vacuum or inert-gas atmospheres.

- Non-Metals: Graphite and Silicon Carbide are also used for very high-temperature processes. Graphite is common in vacuum furnaces due to its high-temperature stability and low cost, while Silicon Carbide is valued for its ability to operate in air at temperatures far exceeding the limits of metallic alloys.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Selecting the right material involves navigating a series of critical trade-offs that directly impact cost, performance, and operational lifespan.

Cost vs. Temperature Performance

There is a direct correlation between a material's maximum operating temperature and its cost. CuNi alloys are relatively inexpensive for low-temperature use, while NiCr and FeCrAl represent a mid-range balance for high-temperature air heating. The price increases significantly for refractory metals like Tungsten and Molybdenum.

Operating Environment: Air vs. Vacuum

The single most important environmental factor is the presence of oxygen. NiCr and FeCrAl are designed specifically to perform in air. Conversely, materials like Tungsten, Molybdenum, and Graphite must be used in a vacuum or inert atmosphere to prevent them from rapidly burning up.

Brittleness and Formability

Materials like Tungsten are very brittle at room temperature, making them difficult to form into the complex coil shapes often required for heating elements. Softer, more ductile alloys like Nichrome are much easier to manufacture, which also factors into the final cost of the element.

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Your final selection depends entirely on the operational demands of your system.

- If your primary focus is general-purpose heating in air (up to ~1200°C): Nickel-Chromium (NiCr) alloys offer the best all-around balance of performance, reliability, and cost.

- If your primary focus is industrial furnaces requiring very high temperatures in air: Iron-Chromium-Aluminum (FeCrAl) is a durable and often more cost-effective alternative to NiCr.

- If your primary focus is low-temperature heating (<400°C) or precision resistors: Copper-Nickel (CuNi) provides the ideal combination of moderate resistance and excellent formability.

- If your primary focus is extreme temperatures (>1200°C) in a vacuum or inert gas: Refractory metals like Tungsten and Molybdenum, or non-metals like Graphite, are your only viable options.

Choosing the correct heating element material is the foundation for designing a safe, reliable, and efficient thermal system.

Summary Table:

| Material Type | Common Examples | Key Properties | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel-Chromium Alloys | Nichrome (80% Ni, 20% Cr) | High electrical resistivity, excellent oxidation resistance, good mechanical stability | Toasters, hair dryers, industrial heaters |

| Iron-Chromium-Aluminum Alloys | FeCrAl | High temperature resistance, forms protective alumina layer | Industrial furnaces, high-temperature air heating |

| Copper-Nickel Alloys | CuNi | Lower resistivity, excellent corrosion resistance, easy formability | Electric blankets, underfloor heating, precision resistors |

| Refractory Metals | Tungsten, Molybdenum | Very high melting points, requires vacuum/inert atmosphere | Vacuum furnaces, extreme temperature processes |

| Non-Metals | Graphite, Silicon Carbide | High-temperature stability, operates in air or vacuum | High-temperature industrial processes, vacuum furnaces |

Struggling to select the right heating element for your lab's high-temperature needs? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced solutions like Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we precisely meet your unique experimental requirements, enhancing efficiency and reliability. Contact us today to discuss how our tailored heating elements can optimize your thermal systems!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the primary use of a muffle furnace in the assembly of side-heated resistive gas sensors? Expert Annealing Guide

- What role does a muffle furnace play in g-C3N4 synthesis? Mastering Thermal Polycondensation for Semiconductors

- What role does a muffle furnace play in the conversion of S-1@TiO2? Achieve Precision Calcination of Nanospheres

- What is the primary role of a muffle furnace in the annealing process of AlCrTiVNbx alloys? Enhance Alloy Strength

- What role does a muffle furnace play in analyzing the combustion residues? Optimize Your Composite Char Analysis