In a laboratory vacuum furnace, cooling is primarily accomplished through three methods: inert gas quenching, liquid (oil) quenching, and controlled slow cooling. These systems work alongside external water-cooling jackets that protect the furnace itself from overheating. The specific method chosen is critical, as it directly determines the final metallurgical properties of the workpiece.

The selection of a cooling system is not about the furnace, but about the material. The core challenge is matching the cooling rate—from extremely fast to deliberately slow—to the precise phase transformation or stress relief required to achieve the desired material properties.

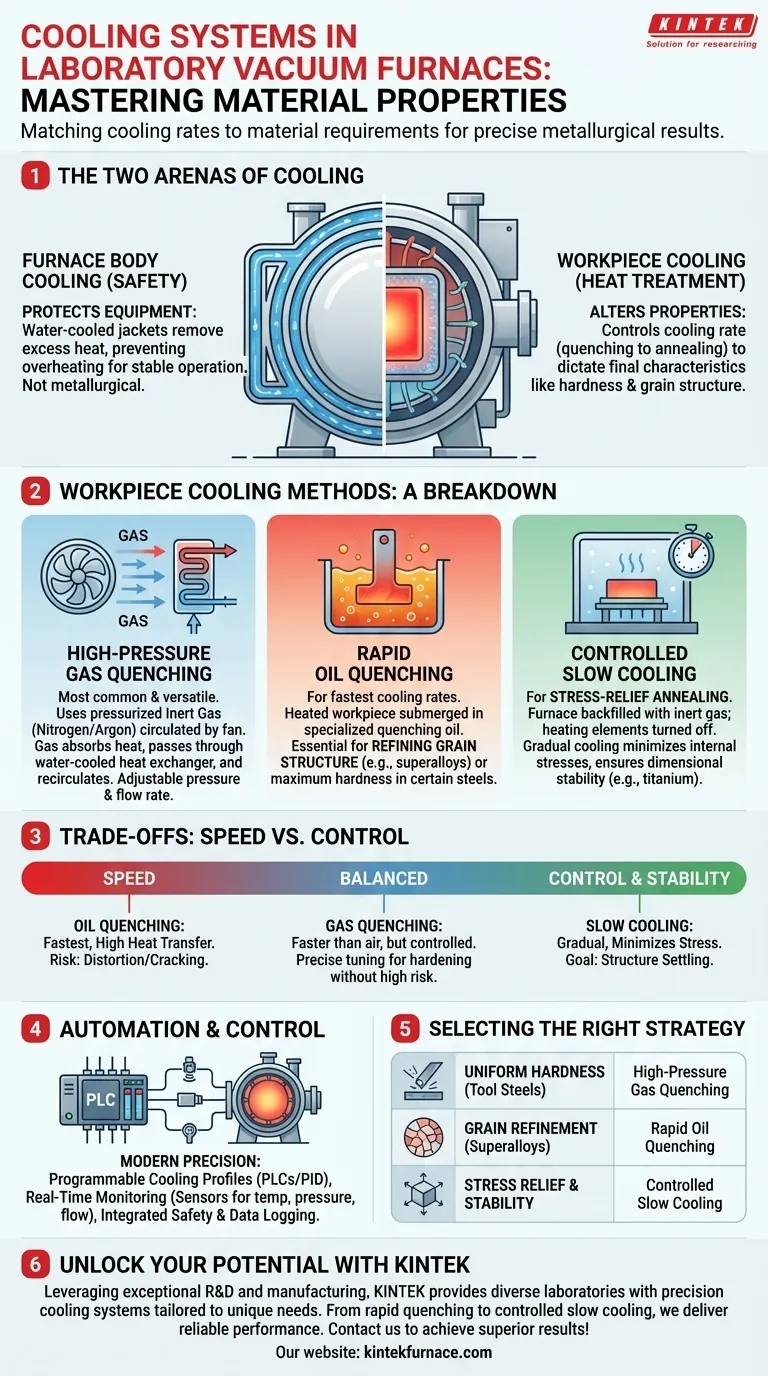

The Two Arenas of Cooling

In any vacuum furnace, cooling occurs in two distinct areas: the furnace body itself and the material being processed (the workpiece). Confusing the two is a common mistake.

Furnace Body Cooling

This system's only job is to protect the equipment. Water-cooled jackets are circulated around the furnace chamber to remove excess heat, preventing the furnace walls from overheating and ensuring safe, stable operation. This is a safety and operational feature, not a metallurgical process.

Workpiece Cooling (Heat Treatment)

This is the process that directly alters the properties of the material inside the furnace. The goal here is to control the rate at which the workpiece cools, which can range from extremely rapid (quenching) to very slow (annealing).

A Breakdown of Workpiece Cooling Methods

The method used to cool the workpiece is the most critical decision in the heat treatment process. It dictates final characteristics like hardness, grain structure, and internal stress.

High-Pressure Gas Quenching

This is the most common and versatile method. After the heating cycle, the chamber is backfilled with a high-purity inert gas, typically nitrogen or argon.

This gas is pressurized, sometimes to twice atmospheric pressure or more, and circulated by a fan. It absorbs heat from the hot workpiece and is then passed through a water-cooled heat exchanger to remove the heat before being recirculated. This cycle repeats until the part is cool.

Rapid Oil Quenching

For cooling rates that gas cannot achieve, oil quenching is used. The heated workpiece is submerged in a bath of specialized quenching oil.

This provides extremely rapid heat transfer, which is necessary for refining the grain structure in materials like nickel-based superalloys or achieving maximum hardness in certain steel alloys.

Controlled Slow Cooling

The opposite of quenching, slow cooling is used for processes like stress-relief annealing. Instead of rapid cooling, the furnace is simply backfilled with an inert gas and the heating elements are turned off.

This allows the part to cool down gradually over a longer period, minimizing the introduction of new internal stresses. This is crucial for maintaining the dimensional stability of components, especially for materials like titanium.

Understanding the Trade-offs: Speed vs. Control

The choice between gas, oil, and slow cooling involves a fundamental trade-off between cooling speed, process control, and the risk of material damage.

The Need for Speed: Oil Quenching

Oil quenching offers the fastest cooling rates. However, this speed comes at the cost of control and introduces a higher risk of part distortion or even cracking due to thermal shock. It is reserved for specific alloys that demand it.

The Balanced Approach: Gas Quenching

Gas quenching is significantly faster than open-air cooling but more controlled and less severe than oil. The cooling rate can be precisely tuned by adjusting the gas pressure and flow rate, offering excellent versatility for hardening tool steels and other alloys without the high risk of distortion.

The Goal of Precision: Slow Cooling

Slow cooling prioritizes control and stability above all else. The goal is not to induce a phase change but to allow the material's internal structure to settle, relieving stresses built up during manufacturing or previous heat treatments.

The Role of Automation and Control

Modern laboratory furnaces do not rely on manual operation for these critical processes. Sophisticated automation ensures precision and repeatability.

Programmable Cooling Profiles

Furnaces use Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) or PID systems that allow operators to define precise, multi-segment cooling profiles. You can program a specific cooling rate (e.g., °C per minute), hold times, and gas pressures.

Real-Time Monitoring

Embedded sensors continuously monitor temperature, pressure, and gas flow. This data provides real-time feedback to the control system, ensuring the cooling cycle proceeds exactly as programmed.

Integrated Safety and Data

These control systems are integrated with safety features like over-temperature protection and auto-shutdown mechanisms. They also enable data logging for process verification, quality control, and research documentation.

Selecting the Right Cooling Strategy

Your choice must be driven by the end goal for your material.

- If your primary focus is achieving uniform hardness in tool steels: High-pressure gas quenching provides a fast, yet highly controllable, cooling path.

- If your primary focus is refining grain structure in nickel-based superalloys: Rapid oil quenching is the most effective method for achieving the necessary cooling speed.

- If your primary focus is ensuring dimensional stability and stress relief: Controlled slow cooling via inert gas backfilling is the required approach.

Ultimately, mastering the cooling cycle is as important as the heating cycle for unlocking the full potential of your materials.

Summary Table:

| Cooling Method | Key Features | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Pressure Gas Quenching | Controlled cooling via inert gas, adjustable pressure/flow | Hardening tool steels, versatile alloy treatment |

| Rapid Oil Quenching | Fastest cooling, high heat transfer | Grain refinement in superalloys, high-hardness steels |

| Controlled Slow Cooling | Gradual cooling, minimizes stress | Stress relief annealing, dimensional stability in titanium |

Unlock the full potential of your materials with KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnace solutions. Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with precision cooling systems tailored to your unique needs. Our product line includes Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems, all backed by strong deep customization capabilities. Whether you require rapid quenching for superalloys or controlled slow cooling for stress relief, KINTEK delivers reliable performance and enhanced efficiency. Contact us today to discuss how we can support your specific heat treatment challenges and achieve superior results!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

People Also Ask

- What are the components of a vacuum furnace? Unlock the Secrets of High-Temperature Processing

- Why does heating steel rod bundles in a vacuum furnace eliminate heat transfer paths? Enhance Surface Integrity Today

- What is the vacuum heat treatment process? Achieve Superior Surface Quality and Material Performance

- What are the functions of a high-vacuum furnace for CoReCr alloys? Achieve Microstructural Precision and Phase Stability

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance