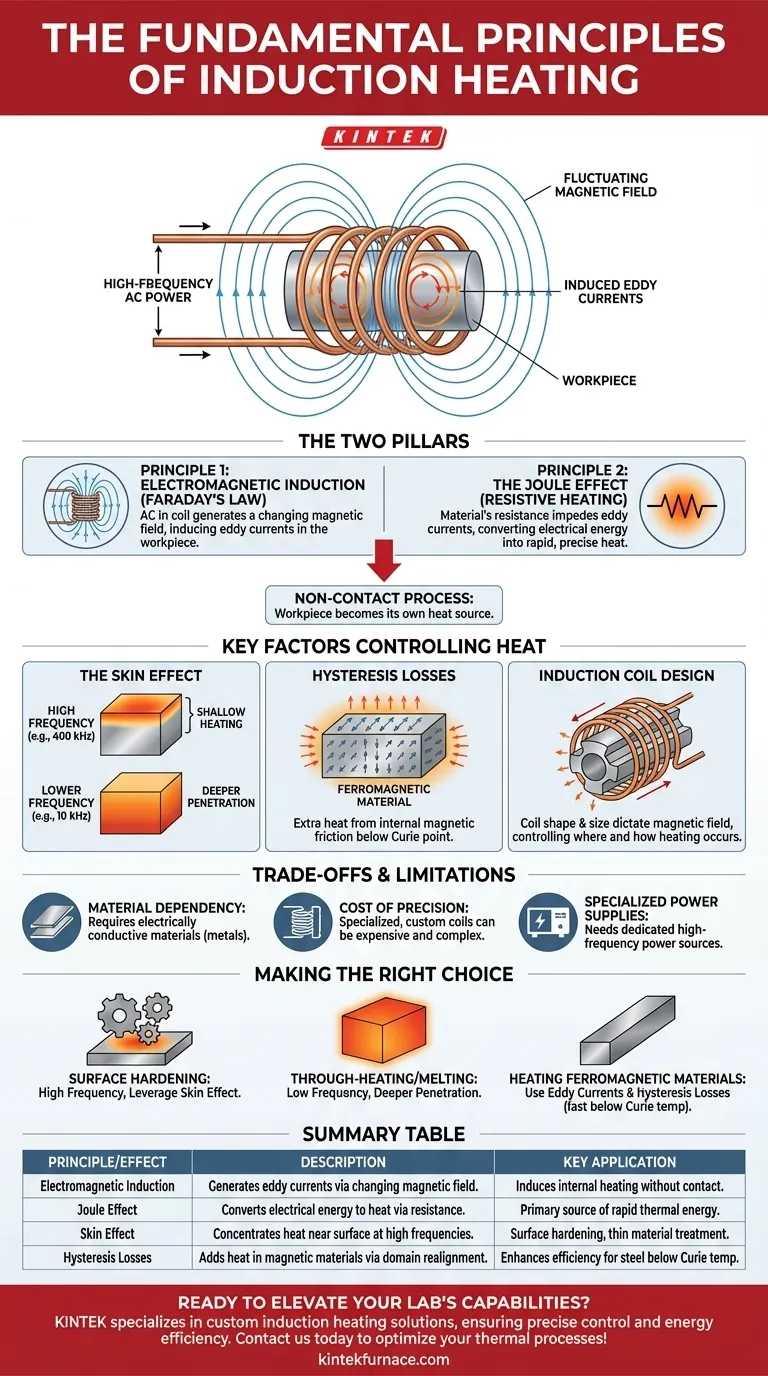

At its core, induction heating operates on two foundational principles: electromagnetic induction and the Joule effect. This non-contact process uses a fluctuating magnetic field to induce electrical currents directly within a conductive material. These internal currents, flowing against the material's own electrical resistance, generate rapid and precise heat.

Instead of applying an external flame or heating element, induction heating ingeniously turns the target object into its own heat source. It uses magnetism to wirelessly generate internal electrical currents, producing clean, controllable heat exactly where it is needed.

The Two Pillars of Induction Heating

To understand induction, you must first grasp the two physical phenomena that work in tandem. One creates the electrical current, and the other converts that current into thermal energy.

Principle 1: Electromagnetic Induction (Faraday's Law)

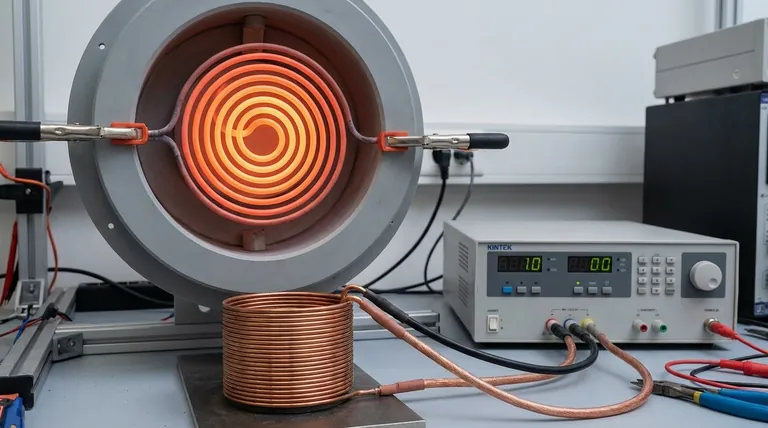

The process begins with an induction coil, typically made of copper tubing, through which a high-frequency alternating current (AC) is passed.

According to Faraday's Law of Induction, this AC flow generates a powerful and rapidly changing magnetic field around the coil.

When an electrically conductive workpiece (like a piece of metal) is placed within this magnetic field, the field induces circular electrical currents inside the material. These are known as eddy currents.

Principle 2: The Joule Effect (Resistive Heating)

The second stage is simple and direct. The induced eddy currents flow through the workpiece, encountering the material's inherent electrical resistance.

Just as a standard resistor heats up when current passes through it, this resistance impedes the flow of the eddy currents, converting the electrical energy into thermal energy. This phenomenon is the Joule effect, and it is the primary source of heat in induction processes.

The amount of heat generated is directly proportional to both the material's resistance and the square of the current, making it an extremely effective heating method.

Key Factors That Control the Heat

Merely generating heat isn't enough; control is what makes induction a valuable industrial process. Several secondary effects and system components allow for precise manipulation of the heating pattern.

The Skin Effect: Concentrating the Power

At the high frequencies used in induction heating, eddy currents do not flow uniformly through the material. They are concentrated in a thin layer near the surface—an effect known as the skin effect.

This is a critical feature, not a limitation. By adjusting the frequency of the AC power supply, you can control the depth of this heated layer. A higher frequency results in shallower heating, ideal for surface hardening, while a lower frequency allows heat to penetrate deeper into the workpiece.

Hysteresis Losses: An Extra Boost for Magnetic Materials

For ferromagnetic materials like iron, nickel, and cobalt, a secondary heating mechanism contributes to the process. The rapidly changing magnetic field causes the material's magnetic domains to rapidly flip their orientation.

This constant re-alignment creates internal friction, which generates additional heat. This effect, known as hysteresis loss, adds to the primary heating from the Joule effect, making induction exceptionally efficient for these materials. This effect ceases once the material is heated above its Curie temperature, where it loses its magnetic properties.

The Role of the Induction Coil

The induction coil is not just a simple wire; it is a precisely engineered tool. Its shape, size, and number of turns dictate the shape and intensity of the magnetic field.

This means the coil's design directly controls where and how the workpiece is heated. This is why coils are often custom-designed for specific applications, whether it's heating a small, precise area for brazing or a large surface for hardening.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Limitations

While powerful, induction heating is not a universal solution. Its effectiveness is governed by clear physical constraints.

Material Dependency

The entire process relies on the workpiece being electrically conductive. Induction is highly effective for metals but works poorly or not at all for non-conductive materials like plastics, glass, or ceramics.

The Cost of Precision: Coil Design

The need for specialized coils can be a significant factor. Designing and manufacturing a durable, efficient inductor for a complex geometry requires expertise and can be expensive. The high currents involved also demand robust engineering, often including internal water cooling for the copper coil itself.

Specialized Power Supplies

Generating the high-frequency alternating current required for induction heating necessitates a specialized power supply. These systems are more complex and costly than the simple power sources used for conventional resistance heating.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Understanding these principles allows you to match the technology to the industrial task at hand.

- If your primary focus is surface hardening or treating thin materials: You will leverage the skin effect by using high frequencies (e.g., 100-400 kHz) to concentrate heat near the surface.

- If your primary focus is through-heating or melting a large object: You will use lower frequencies (e.g., 1-50 kHz) to allow the magnetic field to penetrate deeper into the material for more uniform heating.

- If your primary focus is heating ferromagnetic materials like steel: You will benefit from both eddy currents and hysteresis losses, making the process exceptionally fast and energy-efficient below the Curie temperature.

By mastering these core principles, you can effectively harness induction heating for rapid, clean, and highly controlled thermal processing.

Summary Table:

| Principle/Effect | Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Electromagnetic Induction | Generates eddy currents in conductive materials via a changing magnetic field. | Induces internal heating without direct contact. |

| Joule Effect | Converts electrical energy to heat due to material resistance from eddy currents. | Primary source of rapid and controlled thermal energy. |

| Skin Effect | Concentrates heating near the surface at high frequencies for shallow penetration. | Ideal for surface hardening and thin material treatments. |

| Hysteresis Losses | Adds extra heat in ferromagnetic materials from magnetic domain realignment. | Enhances efficiency for materials like steel below Curie temperature. |

Ready to elevate your lab's capabilities with advanced heating solutions? KINTEK specializes in custom high-temperature furnace systems, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Leveraging our exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we deliver tailored induction heating solutions that ensure precise temperature control, energy efficiency, and reliability for your unique experimental needs. Contact us today to discuss how we can optimize your thermal processes and drive your research forward!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Silicon Carbide SiC Thermal Heating Elements for Electric Furnace

- Molybdenum Disilicide MoSi2 Thermal Heating Elements for Electric Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

People Also Ask

- Why are SiC heating elements considered environmentally friendly? Discover Their Eco-Efficiency & Lifespan Insights

- What makes SIC heating elements superior for high-temperature applications? Unlock Efficiency and Durability

- What are the properties and capabilities of Silicon Carbide (SiC) as a heating element? Unlock Extreme Heat and Durability

- Why is silicon carbide resistant to chemical reactions in industrial furnaces? Unlock Durable High-Temp Solutions

- What are the properties and applications of silicon carbide (SiC)? Unlock High-Temperature Performance