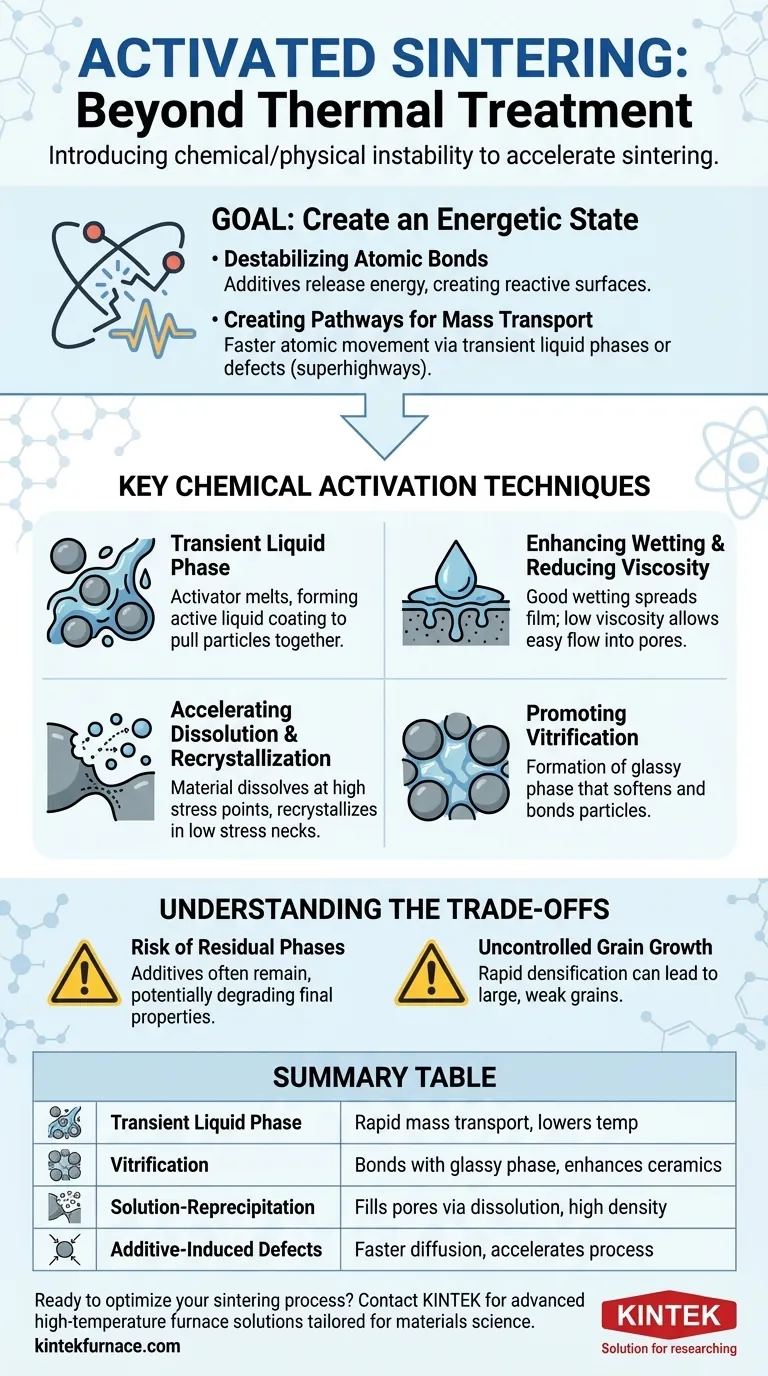

Beyond simple thermal treatment, activated sintering employs advanced techniques that introduce chemical or physical instability to accelerate the process. These methods involve adding specific substances that undergo phase changes or decomposition, creating a highly energetic state within the material that dramatically enhances atomic mobility and bonding, often at significantly lower temperatures.

The central strategy of activated sintering is not merely to heat a material, but to intentionally destabilize its atomic structure. By introducing activators that create transient liquid phases or lattice defects, you create high-speed pathways for mass transport, making the densification process far more efficient.

The Goal of Activation: Creating an Energetic State

To understand these techniques, you must first understand their fundamental goal: to make it easier for atoms to move and for particles to bond together. This bypasses the slow, energy-intensive process of traditional solid-state sintering.

Destabilizing Atomic Bonds

The core of activation lies in disrupting the stable atomic or ionic bonds in the powder particles. Additives that decompose or change phase upon heating release energy and create chemically reactive surfaces.

This "active state" means the atoms at the particle surfaces are less stable and more inclined to move, which is the essential requirement for sintering necks to form and grow.

Creating Pathways for Mass Transport

In conventional sintering, atoms slowly diffuse through the solid lattice. Activation techniques create superhighways for this mass transport.

By introducing a temporary liquid or a highly defective surface, atoms can move hundreds or thousands of times faster than they could through a solid crystal, accelerating densification.

Key Chemical Activation Techniques

The most common methods involve the careful selection of additives that manipulate the chemistry and physics at the particle interfaces during heating.

Forming a Transient Liquid Phase

A primary technique is to add a small amount of a material that melts at a temperature below the main powder's sintering temperature.

This creates an "active liquid phase" that coats the solid particles. This liquid acts as a solvent and a medium for rapid mass transport, pulling the solid particles together through capillary action.

Enhancing Wetting and Reducing Viscosity

For a liquid phase to be effective, it must wet the solid particles, meaning it spreads out to form a thin, continuous film. Good wetting maximizes the capillary force that rearranges and densifies the powder compact.

Furthermore, the liquid must have a low viscosity so it can flow easily into the small pores between particles, ensuring it can facilitate mass transport throughout the entire component.

Accelerating Dissolution and Recrystallization

Once the liquid phase forms and wets the particles, the densification process accelerates. The solid material dissolves into the liquid at points of high stress (like particle contacts).

These dissolved atoms then rapidly diffuse through the liquid and recrystallize (precipitate) in low-stress areas, such as the "necks" growing between particles. This process, known as solution-reprecipitation, is the mechanism that fills pores and densifies the material.

Promoting Vitrification

In some systems, particularly ceramics, the additive may not form a true crystalline liquid but instead promotes vitrification.

This is the formation of a glassy, non-crystalline phase that softens and flows at high temperatures. This viscous glass can serve a similar function to a liquid phase, filling voids and bonding particles together.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While powerful, these activation techniques introduce complexities and potential downsides that must be managed.

Risk of Residual Phases

The additives used for activation rarely disappear completely. They often remain in the final microstructure as a secondary phase, typically at the grain boundaries.

This residual phase can be detrimental to the final properties of the material, potentially degrading its mechanical strength, thermal conductivity, or electrical resistance. Careful selection and minimal use of additives are critical.

Uncontrolled Grain Growth

The same high-energy environment that accelerates densification can also lead to rapid and undesirable grain growth.

While densification is the goal, excessively large grains can significantly weaken the final material. A key challenge is to optimize the process to achieve full density while keeping the grain size small.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The ideal activation strategy depends entirely on your specific objective for the material and process.

- If your primary focus is lowering the sintering temperature: Choose an activator that forms a low-melting-point eutectic liquid phase with your primary material to enable mass transport far below its normal sintering point.

- If your primary focus is achieving maximum density: Prioritize an activator system that provides excellent wetting and low liquid viscosity to ensure the liquid phase can effectively penetrate all pores and pull particles together.

- If your primary focus is preserving a fine-grained microstructure: Use the absolute minimum amount of activator required and design a rapid heating and cooling cycle to complete densification before significant grain growth can occur.

Ultimately, these techniques transform sintering from a brute-force thermal process into a precise, chemically-engineered manufacturing method.

Summary Table:

| Technique | Key Mechanism | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Transient Liquid Phase | Forms low-melting-point liquid for rapid mass transport | Lowers sintering temperature |

| Vitrification | Creates glassy phase to bond particles | Enhances densification in ceramics |

| Solution-Reprecipitation | Dissolves and recrystallizes material to fill pores | Achieves high density |

| Additive-Induced Defects | Introduces lattice instability for faster atomic diffusion | Accelerates overall sintering process |

Ready to optimize your sintering process? At KINTEK, we leverage exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnace solutions tailored for materials science. Our product line—including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems—is designed to support activated sintering with precise temperature control and deep customization. Whether you're aiming to lower sintering temperatures, achieve maximum density, or preserve fine microstructures, our expertise ensures your lab's success. Contact us today to discuss how we can meet your unique experimental needs!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- How does a laboratory muffle furnace facilitate the biomass carbonization process? Achieve Precise Biochar Production

- What role does a muffle furnace play in the preparation of MgO support materials? Master Catalyst Activation

- What is the primary function of a muffle furnace for BaTiO3? Master High-Temp Calcination for Ceramic Synthesis

- Why is a high-performance muffle furnace required for the calcination of nanopowders? Achieve Pure Nanocrystals

- What environmental conditions are critical for SiOC ceramicization? Master Precise Oxidation & Thermal Control