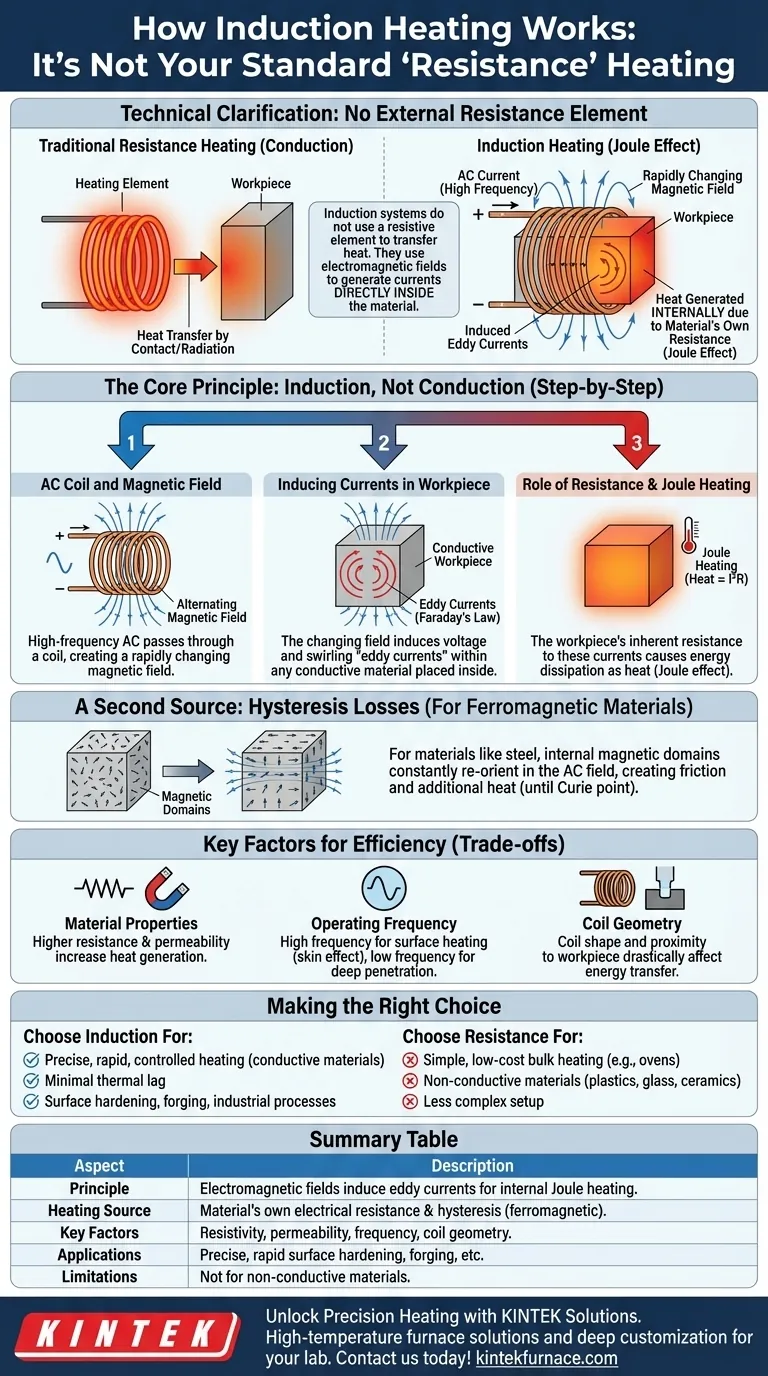

Technically, there is no "resistance heating" in an induction heater in the way you might think of a conventional electric stove. An induction system does not use a resistive element to get hot and then transfer that heat. Instead, it uses electromagnetic fields to generate electrical currents directly inside the target material, and it is the material's own internal resistance to these currents that causes it to heat up from within.

The core misunderstanding is one of method. A resistance heater passes current through a dedicated heating element. An induction heater uses a magnetic field to create currents within the workpiece itself, relying on the workpiece's inherent resistance to generate heat via the Joule effect.

The Core Principle: Induction, Not Conduction

A traditional resistance heater works by conduction. Electricity is forced through a material with high resistance (a heating element), causing it to glow red-hot. That heat then transfers to the target object through physical contact or radiation.

Induction heating is a non-contact process. The heat is generated inside the workpiece, not transferred to it from an external source. This is achieved through the principles of electromagnetism.

Step 1: The AC Coil and the Magnetic Field

The process begins with an induction coil, typically made of copper tubing. A high-frequency alternating current (AC) is passed through this coil.

According to the laws of electromagnetism, any electric current generates a magnetic field. Because the current is alternating, it produces a magnetic field that rapidly changes direction and intensity.

Step 2: Inducing Currents in the Workpiece

When a conductive material (like a piece of steel or copper) is placed within this rapidly changing magnetic field, something remarkable happens.

Faraday's Law of Induction states that a changing magnetic field will induce a voltage, and therefore a current, in any conductor within it. These are called eddy currents—small, swirling loops of current created inside the material itself.

Step 3: The Role of Resistance and Joule Heating

This is where "resistance" enters the picture. The workpiece material is not a perfect conductor; it has inherent electrical resistance.

As the induced eddy currents flow through the material, they encounter this resistance. This opposition causes energy to be dissipated in the form of heat. This phenomenon is known as Joule heating or the Joule effect.

The amount of heat generated is described by Joule's first law: Heat = I²R, where 'I' is the current and 'R' is the resistance. The intense eddy currents flowing against the material's internal resistance generate rapid and significant heat.

A Second Source of Heat: Hysteresis Losses

For certain materials, there is a secondary heating effect that works alongside Joule heating.

What is Magnetic Hysteresis?

This effect only applies to ferromagnetic materials like iron and steel. These materials are composed of tiny magnetic regions called "domains."

When exposed to the heater's alternating magnetic field, these domains rapidly flip back and forth, trying to align with the field. This constant re-orientation creates a type of internal friction, which generates additional heat.

When Hysteresis Matters

Hysteresis losses contribute significantly to the heating of magnetic materials, but this effect stops once the material reaches its Curie temperature—the point at which it loses its magnetic properties. Above this temperature, all further heating is due only to the eddy currents and Joule heating.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Key Factors

The efficiency of induction heating is not universal; it depends entirely on a few key variables. Understanding these is critical to applying the technology correctly.

Material Properties

The electrical resistivity and magnetic permeability of the workpiece are crucial. A material with higher resistance will generate more heat from the same amount of eddy current (I²R). Materials with high magnetic permeability allow for stronger induced currents in the first place.

Operating Frequency

The frequency of the AC current in the coil dictates how the heat is generated.

- High frequencies (e.g., >100 kHz) cause the eddy currents to flow in a thin layer near the surface of the material. This is known as the skin effect and is ideal for surface hardening.

- Low frequencies (e.g., <10 kHz) penetrate deeper into the material, allowing for uniform heating of an entire part, such as for forging.

Coil Geometry

The efficiency of energy transfer depends heavily on the shape of the induction coil and its proximity to the workpiece. A tightly coupled coil transfers energy far more effectively than one that is distant or poorly shaped for the part.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The key is to distinguish between heating with an external element and generating heat from within.

- If your primary focus is precise, rapid, and controlled heating of a conductive material: Induction is superior because the heat is generated exactly where you need it, with minimal thermal lag.

- If your primary focus is simple, low-cost bulk heating (like in an oven): Traditional resistance heating is often more practical, as it is less complex and not dependent on the material's conductive properties.

- If you are working with non-conductive materials (like plastics, glass, or ceramics): Induction heating will not work, as there is no path for the eddy currents required to generate Joule heat.

By understanding that induction leverages a material's own resistance, you can choose the right heating technology for your specific application.

Summary Table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Principle | Uses electromagnetic fields to induce eddy currents in conductive materials, causing internal heating via Joule effect. |

| Heating Source | Material's own electrical resistance and, for ferromagnetic materials, hysteresis losses until Curie temperature. |

| Key Factors | Material resistivity, magnetic permeability, operating frequency, and coil geometry. |

| Applications | Ideal for precise, rapid heating in surface hardening, forging, and other industrial processes. |

| Limitations | Not suitable for non-conductive materials like plastics or ceramics. |

Unlock Precision Heating with KINTEK Solutions

Struggling with inefficient or imprecise heating in your lab? KINTEK specializes in advanced high-temperature furnace solutions tailored to your unique needs. Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we offer a diverse product line including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we can precisely meet your experimental requirements, boosting efficiency and accuracy.

Contact us today to discuss how our induction heating technologies and other solutions can transform your processes and deliver superior results!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Silicon Carbide SiC Thermal Heating Elements for Electric Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- 1400℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz and Alumina Tube

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

People Also Ask

- Why are SiC heating elements considered environmentally friendly? Discover Their Eco-Efficiency & Lifespan Insights

- Why are SIC heating elements resistant to chemical corrosion? Discover the Self-Protecting Mechanism

- What are the properties and capabilities of Silicon Carbide (SiC) as a heating element? Unlock Extreme Heat and Durability

- What makes SIC heating elements superior for high-temperature applications? Unlock Efficiency and Durability

- What is the maximum temperature silicon carbide heating elements can withstand? Key Factors for Longevity and Performance