In essence, you maintain vacuum pressure by creating a dynamic equilibrium. This is achieved when the rate of gas being removed by the vacuum pump is precisely balanced by the rate of all gas entering the vacuum chamber, a process managed with control elements like valves.

The core challenge of maintaining vacuum pressure is not simply pumping harder, but managing the total throughput of the system. Stable pressure is a controlled balance between the gas load entering the chamber and the effective speed at which your pump removes it.

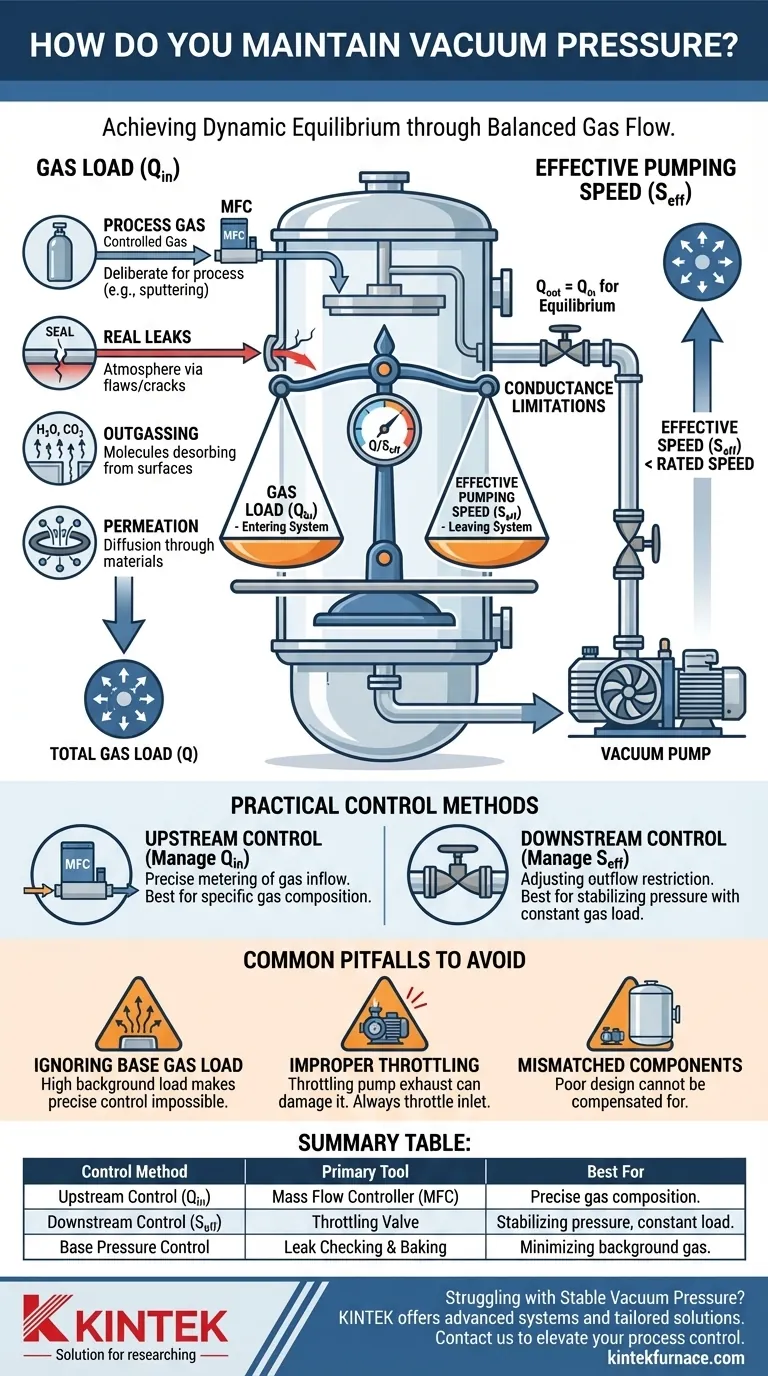

The Fundamental Principle: Throughput Equilibrium

To control pressure, you must first understand the factors that determine it. In any vacuum system, the final pressure is the result of a simple but powerful relationship between gas load and pumping speed.

Understanding Throughput (Q)

Throughput (Q) is the fundamental quantity of gas flow in a vacuum system. It represents the volume of gas moving per unit of time, normalized to its pressure, and is typically measured in Torr-liters/sec or mbar-liters/sec.

The stable pressure (P) in your chamber is determined by this formula: P = Q / S_eff.

Here, Q is the total gas load entering the chamber, and S_eff is the effective pumping speed. To control P, you must actively manage Q or S_eff.

The Gas Load (Q_in): What's Entering Your System

Gas load is the total amount of gas entering the vacuum space per second. It comes from several sources, both intentional and unintentional.

- Process Gas: Gas you deliberately introduce for a specific purpose, like sputtering or chemical vapor deposition. This is your primary controlled gas load.

- Real Leaks: Gas entering from the outside atmosphere through physical flaws like bad seals, cracks, or loose fittings.

- Outgassing: Molecules desorbing from the internal surfaces of the chamber and any components inside it. Water vapor is the most common culprit.

- Permeation: Gas diffusing directly through the solid materials of your chamber, such as elastomer O-rings.

The Pumping Speed (S_eff): What's Leaving Your System

This is the rate at which gas is removed from your chamber. Critically, this is the effective pumping speed at the chamber, not the maximum speed listed on the pump's data sheet.

The effective speed is always lower than the pump's rated speed due to the conductance limitations of the piping, valves, and traps between the pump and the chamber.

Practical Control Methods

With the principle of equilibrium (Q_in = Q_out) in mind, you have two primary levers to pull for maintaining a target pressure.

Method 1: Controlling Gas Inflow (Managing Q_in)

This is known as upstream control. You set a constant pumping speed and precisely meter the amount of gas flowing into the chamber.

This is the preferred method for processes requiring a specific gas composition. It is most often accomplished using a Mass Flow Controller (MFC), which provides an exact, repeatable flow of gas into the system.

Method 2: Controlling Gas Outflow (Managing S_eff)

This is known as downstream control. You introduce a constant flow of gas (or simply work with the existing gas load from leaks and outgassing) and then adjust the effective pumping speed to achieve the target pressure.

This is done by placing a throttling valve (like a butterfly or gate valve) between the chamber and the pump. Partially closing the valve restricts the flow path, reducing S_eff and causing the chamber pressure to rise. Automated control systems can dynamically adjust the valve to hold a very stable pressure.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Achieving stable pressure requires a holistic view of your system. Focusing on just one element while ignoring others is a common source of failure.

Pitfall 1: Ignoring the Base Gas Load

You cannot achieve stable process pressure if your background gas load (from leaks and outgassing) is high or unstable. If your leak rate is 1x10⁻⁴ Torr-L/s and you are trying to control a process at 1x10⁻⁵ Torr, it is impossible.

Always perform a leak check and ensure your chamber is clean before attempting precise pressure control. A system with high integrity is fundamentally easier to control.

Pitfall 2: Throttling a Pump Improperly

While throttling is a powerful control method, it can be detrimental to some pumps. Severely throttling a turbomolecular pump, for instance, can stress its bearings.

Understand the operating limits of your specific pump. Always throttle on the pump's inlet (high vacuum side), never on its exhaust (foreline side).

Pitfall 3: Mismatched System Components

No control system can compensate for a poorly designed vacuum system. Using a massive pump on a small chamber with a tiny gas load will make low-pressure control difficult. Conversely, a small pump on a large, outgassing-prone chamber will struggle to reach the target pressure in the first place.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your strategy for maintaining pressure depends entirely on your objective.

- If your primary focus is high-precision process control: Use a combination of upstream control (with an MFC to set gas flow) and downstream control (with an automated throttle valve) for the most stable and responsive system.

- If your primary focus is reaching and holding a stable base pressure: Your goal is to minimize all sources of gas load. This means you must find and fix leaks, use clean, low-outgassing materials, and potentially perform a system bake-out.

- If your primary focus is a rough vacuum for a simple process: A simple manual needle valve on the gas inlet or a manual throttle valve on the pump may be perfectly sufficient and far more cost-effective.

Ultimately, mastering vacuum pressure comes from viewing your system as a dynamic balance of gas sources and sinks.

Summary Table:

| Control Method | Primary Tool | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Upstream Control (Manage Q_in) | Mass Flow Controller (MFC) | Processes requiring precise gas composition. |

| Downstream Control (Manage S_eff) | Throttling Valve | Stabilizing pressure with a constant gas load. |

| Base Pressure Control | Leak Checking & Baking | Minimizing background gas from leaks/outgassing. |

Struggling to Achieve Stable Vacuum Pressure for Your Critical Processes?

Precise pressure control is fundamental to successful R&D and manufacturing. KINTEK understands that every application—from thin-film deposition to advanced materials synthesis—has unique vacuum requirements.

We provide more than just equipment; we deliver tailored solutions. Leveraging our exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing capabilities, we offer:

- Advanced High-Temperature Furnaces (Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere) with integrated vacuum systems.

- CVD/PECVD Systems engineered for precise atmospheric control.

- Strong Deep Customization to precisely match your specific gas load, pumping speed, and process control needs.

Let us help you master the balance. Our experts will work with you to design or optimize a system that ensures the stable, reliable vacuum pressure your laboratory depends on.

Contact KINTEK today for a consultation and elevate your vacuum process control.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 304 316 Stainless Steel High Vacuum Ball Stop Valve for Vacuum Systems

- Ultra Vacuum Electrode Feedthrough Connector Flange Power Lead for High Precision Applications

- CF KF Flange Vacuum Electrode Feedthrough Lead Sealing Assembly for Vacuum Systems

- Stainless Steel Quick Release Vacuum Chain Three Section Clamp

- High Performance Vacuum Bellows for Efficient Connection and Stable Vacuum in Systems

People Also Ask

- Why is a high vacuum pumping system necessary for carbon nanotube peapods? Achieve Precise Molecular Encapsulation

- Why is it necessary to maintain a pressure below 6.7 Pa during stainless steel refining? Achieve Ultra-High Purity

- What is the significance of high-precision mass flow controllers in testing NiFe2O4? Ensure Data Integrity

- What role do the exhaust branch pipes at the top of a vacuum chamber play? Optimize Your Pressure Control Today

- What components make up the vacuum system of a vacuum furnace? Unlock Precision for High-Temperature Processing