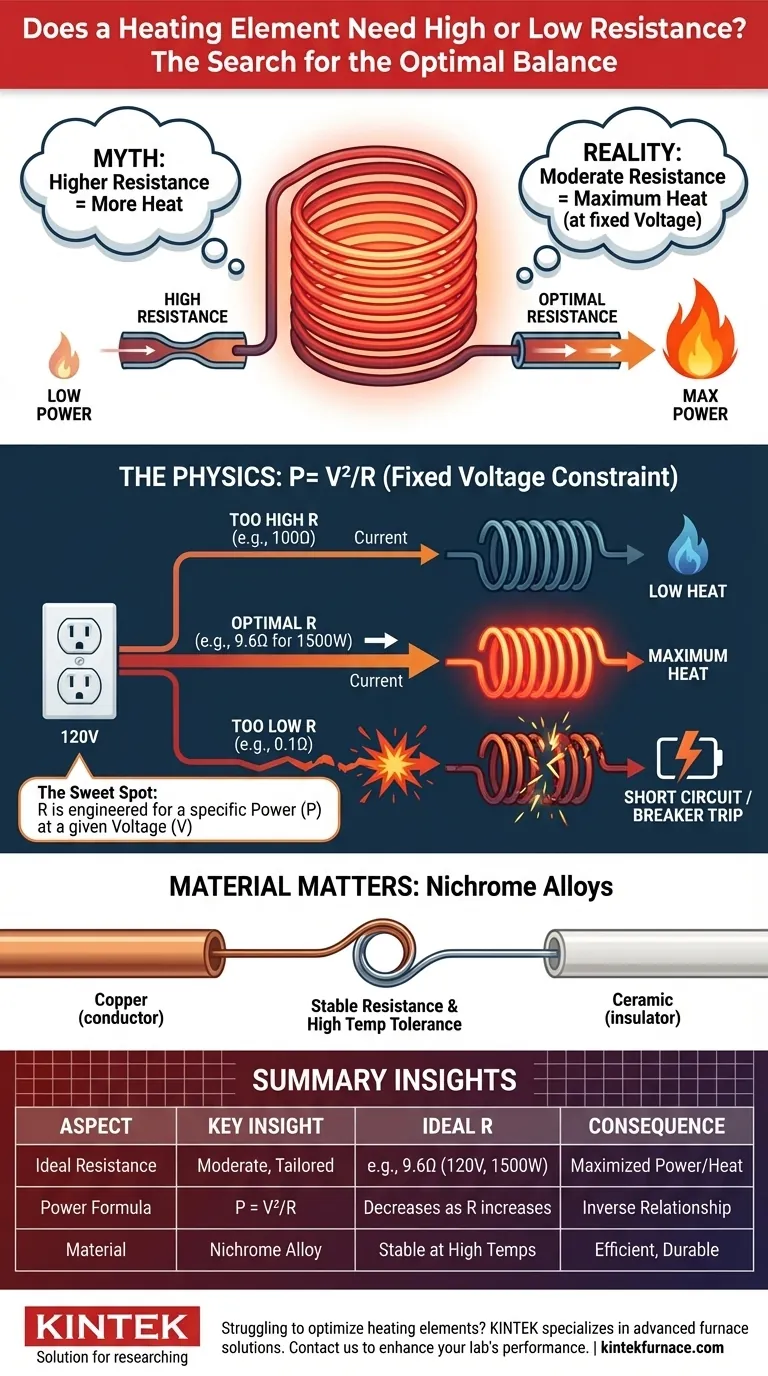

The effectiveness of a heating element depends not on maximizing resistance, but on achieving an optimal balance. A common misconception is that higher resistance always equals more heat. In reality, a heating element requires a moderate, carefully calculated resistance tailored to its voltage source to produce the maximum amount of heat.

The core principle is that heat output is a function of power, which depends on both resistance and the current flowing through it. For a fixed voltage source like a wall outlet, too much resistance will choke the flow of current, drastically reducing power and heat. The goal is to optimize resistance to maximize power draw, not resistance itself.

The Physics of Heat Generation

To understand why a "medium" resistance is ideal, we must look at the relationship between voltage, current, resistance, and power. Heat is a direct result of electrical power dissipated by the element.

The Role of Power (Joule's Law)

The heat generated by an element is defined by its power output (P), measured in watts. This is governed by Joule's Law, which can be expressed in two key ways:

- P = I²R (Power equals current squared times resistance)

- P = V²/R (Power equals voltage squared divided by resistance)

These equations show that power is not dependent on resistance alone; it is critically linked to current (I) and voltage (V).

The Fixed Voltage Constraint

Nearly all common heating appliances, from toasters to water heaters, are plugged into a fixed-voltage power source (e.g., 120V or 240V in a home). This fixed voltage is the most important constraint in the system.

Because voltage (V) is constant, the second formula, P = V²/R, becomes the most insightful. It clearly shows an inverse relationship: if voltage is fixed, increasing the resistance (R) will actually decrease the power (P), and therefore the heat.

Why 'Maximum Resistance' is a Flawed Goal

This reveals the central paradox. While some resistance is necessary to convert electrical energy to heat, an infinitely high resistance would reduce the power output to nearly zero.

This is explained by Ohm's Law (I = V/R). For a fixed voltage, as you increase resistance, you decrease the current. In the P = I²R formula, the current (I) is squared, so its decrease has a much larger impact than the linear increase in resistance (R), ultimately causing power to drop.

Finding the 'Sweet Spot' of Resistance

The engineer's goal is not to maximize resistance but to select a specific resistance value that produces the desired power output from the available voltage.

Matching Resistance to the Power Source

An effective heating element is one whose resistance is low enough to draw a significant amount of current, but high enough to generate heat efficiently without creating a short circuit.

For example, a 1500-watt hair dryer on a 120V circuit has a specific, engineered resistance. Using P = V²/R, we can calculate it:

R = (120V)² / 1500W = 14400 / 1500 = 9.6 Ohms

This is a relatively low resistance, far from the "high" value many assume is necessary.

Properties of Heating Element Materials

This is why specific alloys like Nichrome (nickel-chromium) are used. They have a resistance that is significantly higher than copper (a conductor) but much lower than an insulator.

More importantly, their resistance is stable across a wide range of temperatures, and they resist oxidation, ensuring they don't burn out quickly when glowing red-hot.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing the wrong resistance has clear consequences, demonstrating why the optimal balance is so critical.

The Problem with Too High Resistance

If you were to use a material with extremely high resistance, very little current would be able to flow from the 120V outlet. According to P = V²/R, a very large R results in a very small P. The element would barely get warm.

The Problem with Too Low Resistance

Conversely, if you used a material with near-zero resistance (like a copper wire), you would create a short circuit. Ohm's Law (I = V/R) shows that as R approaches zero, the current (I) skyrockets.

This massive current surge produces a flash of heat but will immediately trip a circuit breaker or blow a fuse. It's an uncontrolled and dangerous state, not a functional heating element.

How to Apply This Principle

Your understanding of "high" or "low" resistance must be framed by your specific electrical goal.

- If your primary focus is maximum heat from a fixed voltage source (e.g., a wall outlet): You need an optimal, moderate resistance designed to produce the highest power (in watts) without exceeding the circuit's amperage limit.

- If you are designing for a fixed current source (less common for appliances): You would indeed seek higher resistance, as the formula P = I²R shows that power is directly proportional to resistance when current is constant.

- If your primary focus is material selection: You need a material with stable resistance at high temperatures, like Nichrome or Kanthal, whose inherent resistivity is in the "sweet spot"—much higher than a conductor but far lower than an insulator.

Ultimately, designing an effective heating element is an engineering exercise in precisely matching the element's resistance to its power source to achieve a target heat output.

Summary Table:

| Aspect | Key Insight |

|---|---|

| Ideal Resistance | Moderate, tailored to voltage for maximum power (e.g., 9.6 Ohms for 1500W at 120V) |

| Power Formula | P = V²/R (for fixed voltage, power decreases as resistance increases) |

| Material Choice | Alloys like Nichrome offer stable resistance at high temperatures |

| Consequences | High resistance reduces heat; low resistance causes short circuits |

Struggling to optimize heating elements for your lab's high-temperature processes? KINTEK specializes in advanced furnace solutions, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. With our strong R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide deep customization to precisely match your experimental needs, ensuring efficient and reliable heat treatment. Contact us today to discuss how we can enhance your laboratory's performance!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- How does a laboratory muffle furnace facilitate the biomass carbonization process? Achieve Precise Biochar Production

- Why is a high-performance muffle furnace required for the calcination of nanopowders? Achieve Pure Nanocrystals

- What substances are prohibited from being introduced into the furnace chamber? Prevent Catastrophic Failure

- What is the key role of a muffle furnace in the pretreatment of boron sludge and szaibelyite? Unlock Higher Process Efficiency

- What is the role of a muffle furnace in the synthesis of water-soluble Sr3Al2O6? Precision in SAO Production