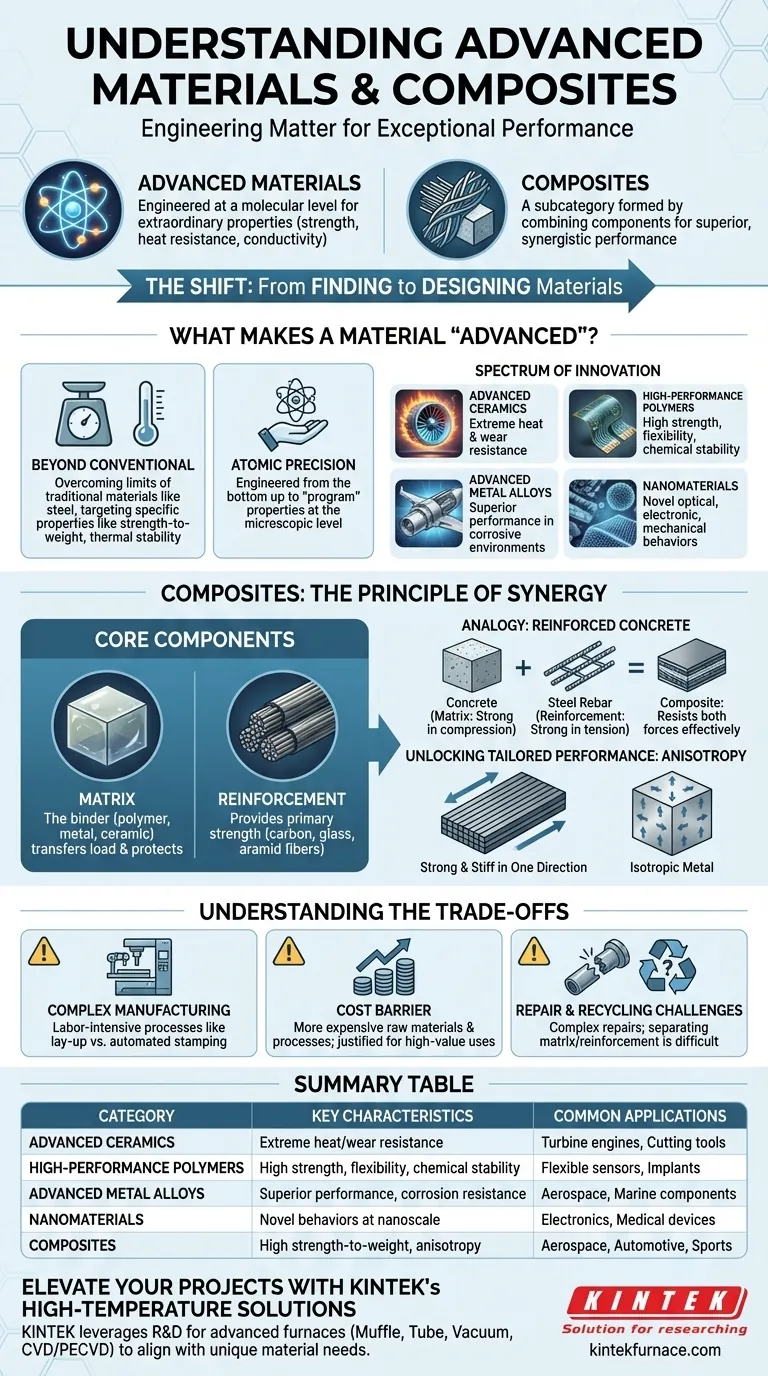

In essence, advanced materials are substances engineered at a molecular level to exhibit exceptional properties—such as superior strength, heat resistance, or conductivity—that far exceed those of traditional materials. Composites are a prominent subcategory of advanced materials, formed by combining two or more distinct components to create a new material with performance characteristics superior to any of its individual parts.

The critical shift is from simply finding materials to intentionally designing them. Advanced materials and composites represent a move towards engineering matter with a specific purpose, unlocking performance capabilities previously thought impossible.

What Makes a Material "Advanced"?

The term "advanced" isn't just a synonym for "new." It signifies a fundamental leap in performance and design intent, driven by control over the material's internal structure.

Beyond Conventional Properties

Traditional materials like steel or aluminum have well-understood, but often fixed, limits. Advanced materials are developed specifically to overcome these limitations, targeting extraordinary improvements in specific areas like strength-to-weight ratio, thermal stability, electrical conductivity, or biocompatibility.

Precision at the Atomic Level

The defining characteristic of these materials is that they are engineered from the bottom up. Scientists and engineers can manipulate the microscopic or even atomic structure to "program" the material's final, macroscopic properties. This allows for an unprecedented level of customization.

A Spectrum of Innovation

Advanced materials encompass a wide range of categories, each with unique potential:

- Advanced Ceramics: Engineered for extreme heat and wear resistance, far beyond what metals can endure.

- High-Performance Polymers: Plastics and elastomers designed for high strength, flexibility, and chemical stability.

- Advanced Metal Alloys: Combinations of metals (like titanium or nickel-based superalloys) created for superior performance in aerospace or corrosive environments.

- Nanomaterials: Materials structured at the nanoscale (1-100 nanometers) to unlock novel optical, electronic, or mechanical behaviors.

Composites: The Principle of Synergy

Composites are perhaps the most well-known example of advanced materials in practice. They are a physical mixture of separate components that remain distinct within the final structure, working together to achieve a common goal.

The Core Components: Matrix and Reinforcement

Nearly all composites consist of two primary elements:

- The Matrix: This is the binder material that holds everything together. It is often a polymer (resin), metal, or ceramic, and its role is to transfer load between the reinforcing fibers and protect them from damage.

- The Reinforcement: This provides the primary strength and stiffness. It typically takes the form of fibers, such as carbon, glass, or aramid, which are incredibly strong for their low weight.

An Analogy: Reinforced Concrete

Think of reinforced concrete. Concrete (the matrix) is strong under compression but cracks easily under tension (pulling forces). Steel rebar (the reinforcement) is exceptionally strong in tension. By embedding the rebar within the concrete, you create a composite material that effectively resists both forces.

Unlocking Tailored Performance

The true power of composites lies in their anisotropy—the ability to have different properties in different directions. By precisely orienting the reinforcing fibers, engineers can make a part incredibly strong and stiff along one axis while allowing for flexibility along another. This is impossible with most metals, which are isotropic (having uniform properties in all directions).

Understanding the Trade-offs

While their performance is impressive, advanced materials and composites are not a universal solution. Their adoption requires navigating a distinct set of challenges.

Complexity in Manufacturing

Producing composite parts often involves complex, labor-intensive processes like manual lay-up, resin infusion, or high-pressure curing in an autoclave. This stands in contrast to the highly automated and rapid processes of stamping or casting traditional metals.

Cost as a Primary Barrier

The raw materials and sophisticated manufacturing required make many advanced materials significantly more expensive than their conventional counterparts. Their use is often justified only in high-value applications where performance benefits like weight savings or durability are mission-critical.

Challenges in Repair and Recycling

Repairing a damaged composite structure is often more complex than fixing a dent in a metal panel. Furthermore, separating the intertwined matrix and reinforcement makes recycling composites an ongoing technical and economic challenge.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The decision to use an advanced material or composite should be driven by a clear understanding of the primary performance driver for your project.

- If your primary focus is maximizing strength-to-weight ratio (e.g., aerospace, racing): Fiber-reinforced polymer composites, especially carbon fiber, are the definitive choice.

- If your primary focus is extreme temperature and wear resistance (e.g., turbine engines, cutting tools): Advanced ceramics and nickel-based superalloys offer performance where other materials would fail.

- If your primary focus is creating novel electronic or biomedical functions (e.g., flexible sensors, biocompatible implants): Investigate the potential of smart polymers, nanomaterials, and specifically designed biocompatible composites.

Ultimately, selecting an advanced material is about precisely matching its engineered capabilities to the unique performance demands of your application.

Summary Table:

| Category | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Ceramics | Extreme heat and wear resistance | Turbine engines, cutting tools |

| High-Performance Polymers | High strength, flexibility, chemical stability | Flexible sensors, biomedical implants |

| Advanced Metal Alloys | Superior performance in corrosive environments | Aerospace, marine components |

| Nanomaterials | Novel optical, electronic, mechanical behaviors | Electronics, medical devices |

| Composites | High strength-to-weight ratio, anisotropy | Aerospace, automotive, sports equipment |

Ready to elevate your projects with custom high-temperature furnace solutions? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced furnaces like Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our deep customization capabilities ensure precise alignment with your unique experimental needs for materials like advanced ceramics and composites. Contact us today to discuss how we can enhance your lab's efficiency and innovation!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- 1200℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- 1400℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- Mesh Belt Controlled Atmosphere Furnace Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- 1700℃ High Temperature Laboratory Tube Furnace with Quartz or Alumina Tube

People Also Ask

- What is an atmosphere protection muffle furnace? Unlock Precise Heat Treatment in Controlled Environments

- What are the development prospects of atmosphere box furnaces in the aerospace industry? Unlock Advanced Material Processing for Aerospace Innovation

- What are some specific applications of atmosphere furnaces in the ceramics industry? Enhance Purity and Performance

- What is inert gas technology used for in high-temperature atmosphere vacuum furnaces? Protect Materials and Speed Up Cooling

- How do argon and nitrogen protect samples in vacuum furnaces? Optimize Your Thermal Process with the Right Gas