In a vacuum furnace, cooling is actively achieved by breaking the vacuum and introducing a controlled medium—typically a high-purity inert gas or a specialized oil—after the heating cycle is complete. Because a vacuum is an excellent insulator, passive radiation is far too slow for most metallurgical processes, making this active intervention necessary to control the final properties of the material.

The core principle is not simply to lower the temperature, but to use the rate of cooling as a deliberate tool. The choice between gas, oil, or slow cooling is a critical step in the heat treatment process itself, directly determining the material’s final hardness, strength, and internal stress.

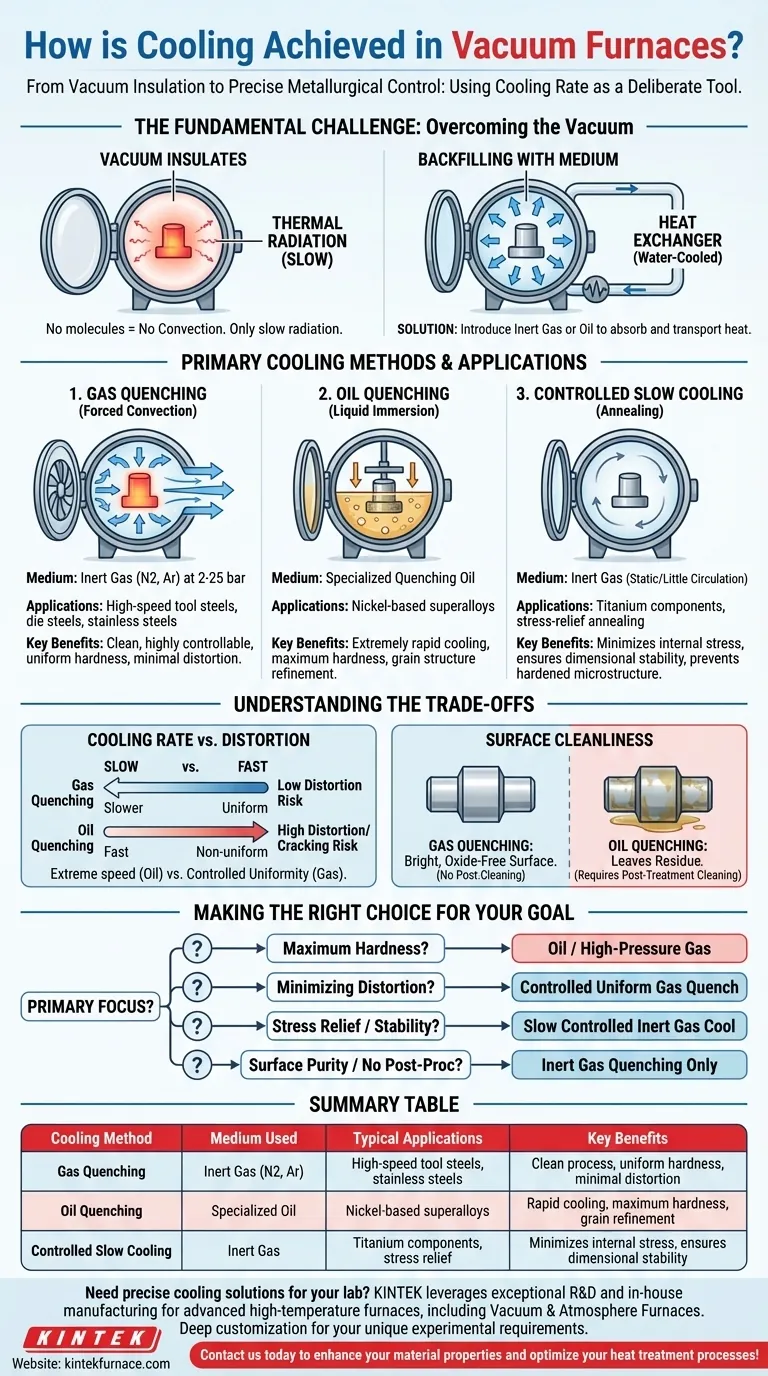

The Fundamental Challenge: Overcoming the Vacuum

Why a Vacuum Insulates

A vacuum chamber is almost entirely devoid of molecules. This prevents heat transfer through convection, the process where a fluid or gas carries heat away from a hot surface.

With convection eliminated, the only significant way for a hot part to cool is through thermal radiation. This process is extremely slow and provides no meaningful control over the cooling rate required for modern materials.

The Solution: Backfilling the Chamber

To achieve rapid and controlled cooling, the furnace chamber is intentionally backfilled with a medium that can absorb and transport heat. This medium makes direct contact with the hot material, enabling efficient heat transfer.

The system then circulates this medium through a heat exchanger, which typically uses water to remove the thermal energy from the system before recirculating the cooled medium back into the chamber.

Primary Cooling Methods and Their Applications

Gas Quenching (Forced Convection)

Gas quenching is a clean and highly controllable cooling method. It involves introducing a high-purity inert gas, such as nitrogen (N2) or argon (Ar), into the chamber.

The gas is often pressurized to between 2 and 25 bar (atmospheres) and circulated at high velocity by a powerful fan. This forced convection rapidly strips heat from the material's surface.

This method is ideal for high-speed tool steels, die steels, and stainless steels, where achieving uniform hardness without contamination is critical. Advanced systems use CFD-optimized nozzles to ensure the gas flow is even across complex part geometries.

Oil Quenching (Liquid Immersion)

For even faster cooling rates, some vacuum furnaces are equipped with an internal oil bath. After the heating cycle, the material is mechanically lowered and submerged into a tank of specialized quenching oil.

The direct liquid contact provides an extremely rapid rate of heat transfer. This is essential for certain materials, such as nickel-based superalloys, where the goal is to refine the material's grain structure and achieve specific mechanical properties.

Controlled Slow Cooling (Annealing)

Not all heat treatment requires rapid quenching. For processes like stress-relief annealing, the goal is to cool the part slowly and evenly to minimize internal stresses.

This is achieved by backfilling the chamber with an inert gas but with little to no forced circulation. This gentle cooling prevents the formation of a hardened microstructure and ensures the material is stable, which is common for treating titanium components.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Cooling Rate vs. Part Distortion

The primary trade-off is speed versus risk. Extremely fast cooling, like that from oil quenching, provides maximum hardness but also generates immense thermal stress. This increases the risk of warping, distortion, or even cracking, especially in parts with complex shapes or varying thicknesses.

Gas quenching, while typically slower than oil, offers a more controlled and uniform cooling process, significantly reducing the risk of distortion.

Surface Cleanliness

Gas quenching is an exceptionally clean process. Because it uses high-purity inert gas, the bright, oxide-free surface finish achieved during vacuum heating is perfectly preserved.

Oil quenching, by contrast, will always leave an oil residue on the part. This necessitates a secondary post-treatment cleaning process, adding time and cost to the overall operation.

System Complexity and Uniformity

Achieving truly uniform cooling with gas requires a sophisticated system of high-pressure fans, heat exchangers, and optimized nozzles. This adds to the furnace's cost and complexity.

While oil quenching is mechanically simpler, it can suffer from non-uniform cooling if a vapor blanket (the Leidenfrost effect) forms on the part's surface, insulating it from the liquid in certain spots.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The correct cooling method is determined entirely by the desired metallurgical outcome for your material.

- If your primary focus is maximum hardness: Oil quenching or high-pressure gas quenching provides the rapid cooling needed to create a hardened martensitic structure in steels.

- If your primary focus is minimizing distortion: A controlled, uniform gas quench is the superior choice for treating complex, high-value components.

- If your primary focus is stress relief and dimensional stability: A slow, controlled cool-down using a static inert gas backfill is the correct process for annealing.

- If your primary focus is surface purity with no post-processing: Inert gas quenching is the only method that preserves the clean surface created in the vacuum.

Ultimately, understanding these cooling mechanisms empowers you to select the precise heat treatment cycle that achieves the exact material properties your project demands.

Summary Table:

| Cooling Method | Medium Used | Typical Applications | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Quenching | Inert Gas (N2, Ar) | High-speed tool steels, stainless steels | Clean process, uniform hardness, minimal distortion |

| Oil Quenching | Specialized Oil | Nickel-based superalloys | Rapid cooling, maximum hardness, grain refinement |

| Controlled Slow Cooling | Inert Gas | Titanium components, stress relief | Minimizes internal stress, ensures dimensional stability |

Need precise cooling solutions for your lab? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnaces, including Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, tailored for diverse laboratory needs. With strong deep customization capabilities, we ensure our products—like Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems—meet your unique experimental requirements. Contact us today to enhance your material properties and optimize your heat treatment processes!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press Tube Furnace

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the vacuum heat treatment process? Achieve Superior Surface Quality and Material Performance

- What are the general operational features of a vacuum furnace? Achieve Superior Material Purity & Precision

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance

- What are the benefits of vacuum heat treatment? Achieve Superior Metallurgical Control

- Why does heating steel rod bundles in a vacuum furnace eliminate heat transfer paths? Enhance Surface Integrity Today