In short, materials with high hardenability are ideal for gas quenching. This includes most high-alloy steels such as high-speed, tool, and die steels, as well as certain stainless steels, high-temperature alloys, and titanium alloys. These materials do not require an extremely rapid cool-down to achieve their desired hardness and microstructure, making the controlled, less severe nature of gas quenching a perfect fit.

The suitability of a material for gas quenching is not about its type, but about its critical cooling rate. Gas quenching is a gentler process than oil, so it is reserved for materials that can harden successfully even when cooled more slowly.

The Core Principle: Hardenability and Cooling Rate

The decision to use gas quenching hinges on a single, critical material property: hardenability. This is often confused with hardness, but they are fundamentally different.

What is Hardenability?

Hardenability is the measure of a material's ability to harden through its entire cross-section, not just on the surface. It is a function of the alloy's chemistry.

Materials with high hardenability are more "forgiving." They can be cooled relatively slowly and still form the desired hard martensitic structure.

Materials with low hardenability must be cooled extremely quickly to achieve full hardness, and if cooled too slowly, will only harden on the very surface.

The Role of Alloying Elements

Alloying elements like chromium, molybdenum, manganese, and nickel are the primary drivers of hardenability in steel.

These elements slow down the internal transformations that occur during cooling. This gives you a wider window of time to cool the part and still achieve the target microstructure, making the material suitable for a less severe gas quench.

Why Critical Cooling Rate Matters

Every hardenable steel has a critical cooling rate—the slowest possible cooling speed that will still result in a fully martensitic structure.

If a material has a low critical cooling rate (meaning it can be cooled slowly), it is a perfect candidate for gas quenching. If it has a high critical cooling rate (must be cooled very fast), it will require a more severe liquid quench like oil or water.

A Breakdown of Suitable Materials

Based on the principle of hardenability, we can identify several families of materials that are well-suited for gas quenching in a vacuum furnace.

High-Alloy Tool and Die Steels

This category includes high-speed steels (HSS), cold and hot work tool steels, and high-carbon, high-chromium steels.

Their rich alloy content gives them excellent hardenability and a low critical cooling rate. Gas quenching is the preferred method as it achieves full hardness while minimizing the risk of distortion and cracking that a harsh oil quench could cause.

Stainless Steels

Many martensitic and precipitation-hardening (PH) stainless steels are suitable for gas quenching. Their high chromium content and other alloying elements provide the necessary hardenability for a successful quench in an inert gas atmosphere.

High-Temperature and Titanium Alloys

Materials like superalloys and titanium alloys are often heat-treated to achieve specific mechanical properties, not just maximum hardness.

Gas quenching provides the clean, controlled, and inert environment necessary to cool these sensitive materials at a precise rate without introducing surface contamination.

Other Candidates

Specialized materials such as certain elastic alloys and magnetic materials can also be processed via gas quenching. The choice depends entirely on their specific transformation characteristics and whether a slow, controlled cool-down meets the processing requirements.

Understanding the Trade-offs: Gas vs. Oil

Choosing a quench method is a balance between process requirements and material limitations. Gas quenching offers significant advantages but is not universally applicable.

Advantage 1: Minimized Distortion

The biggest advantage of gas quenching is the significant reduction in thermal shock. The slower, more uniform cooling drastically reduces the risk of part distortion, warping, and cracking, especially in complex geometries.

Advantage 2: Surface Cleanliness

Parts emerging from a gas quench are clean and bright. This eliminates the need for the costly and messy post-processing steps required to clean parts after an oil quench.

The Limitation: Quench Severity

Traditional gas quenching is less severe than oil. For low-alloy steels (like bearing or spring steels) or parts with very thick cross-sections, a gas quench may not be fast enough to prevent the formation of softer microstructures, failing to achieve the required hardness.

Bridging the Gap: High-Pressure Gas Quenching (HPGQ)

Modern vacuum furnaces can perform High-Pressure Gas Quenching (HPGQ) at pressures of 10, 20 bar, or even higher.

This high-pressure, high-flow process significantly increases the cooling rate, closing the gap with oil quenching. HPGQ makes it possible to successfully gas quench some materials and section sizes that would have traditionally required oil.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your material's properties dictate the available options. Use your primary objective to guide your decision.

- If your primary focus is minimizing distortion and maintaining a clean surface on high-alloy parts: Gas quenching is the ideal choice, providing superior dimensional stability.

- If your primary focus is hardening low-alloy steels or very thick components: A liquid quench like oil is often necessary, unless you have access to a proven HPGQ process suitable for your specific material.

- If your primary focus is process control and purity for sensitive alloys: The inert and highly controllable environment of vacuum gas quenching is unmatched.

Understanding the relationship between your material's hardenability and quench severity empowers you to choose the most effective and efficient heat treatment process.

Summary Table:

| Material Type | Key Characteristics | Suitability for Gas Quenching |

|---|---|---|

| High-Alloy Tool & Die Steels | Rich in alloying elements, high hardenability | Excellent, minimizes distortion |

| Stainless Steels | High chromium content, good hardenability | Suitable for martensitic and PH types |

| High-Temperature & Titanium Alloys | Sensitive to contamination, require controlled cooling | Ideal for purity and precise cooling |

| Other Alloys (e.g., elastic, magnetic) | Specific transformation needs | Depends on critical cooling rate |

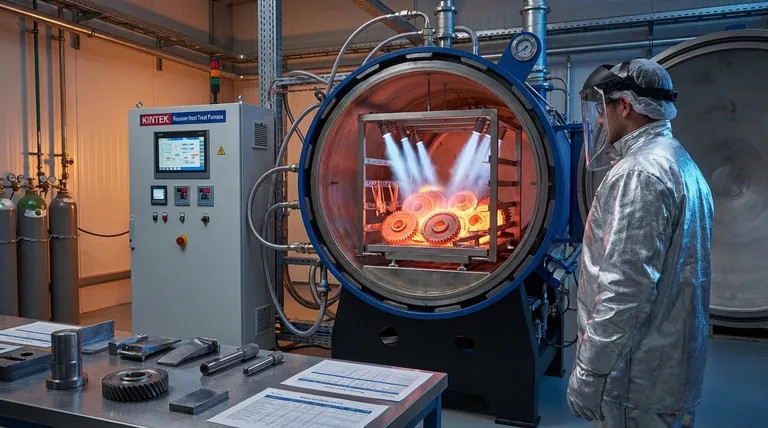

Unlock Precision in Your Heat Treatment with KINTEK

Are you working with high-alloy steels, stainless steels, or sensitive alloys like titanium? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnace solutions tailored to your lab's needs. Our product line includes Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems, all backed by strong deep customization capabilities to meet your unique experimental requirements.

Experience reduced distortion, enhanced surface cleanliness, and superior process control. Contact us today to discuss how our gas quenching solutions can optimize your results and drive efficiency in your laboratory!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the proper procedures for handling the furnace door and samples in a vacuum furnace? Ensure Process Integrity & Safety

- What are the components of a vacuum furnace? Unlock the Secrets of High-Temperature Processing

- Why does heating steel rod bundles in a vacuum furnace eliminate heat transfer paths? Enhance Surface Integrity Today

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in LP-DED? Optimize Alloy Integrity Today

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance