In vacuum sintering, the vacuum degree is the most critical process parameter for controlling the purity and final properties of the sintered material. It is a direct measure of the residual gas pressure inside the furnace chamber; a higher vacuum degree corresponds to a lower pressure and fewer reactive gas molecules. The optimal level is not a single value but is dictated entirely by the chemical reactivity of the material being processed and the specific goals of the sintering cycle.

The significance of the vacuum degree extends far beyond simply preventing rust. It is a strategic tool that directly influences material purity by preventing oxidation, facilitates the removal of contaminants during heating, and actively promotes the atomic-level bonding that gives a sintered part its final strength and density.

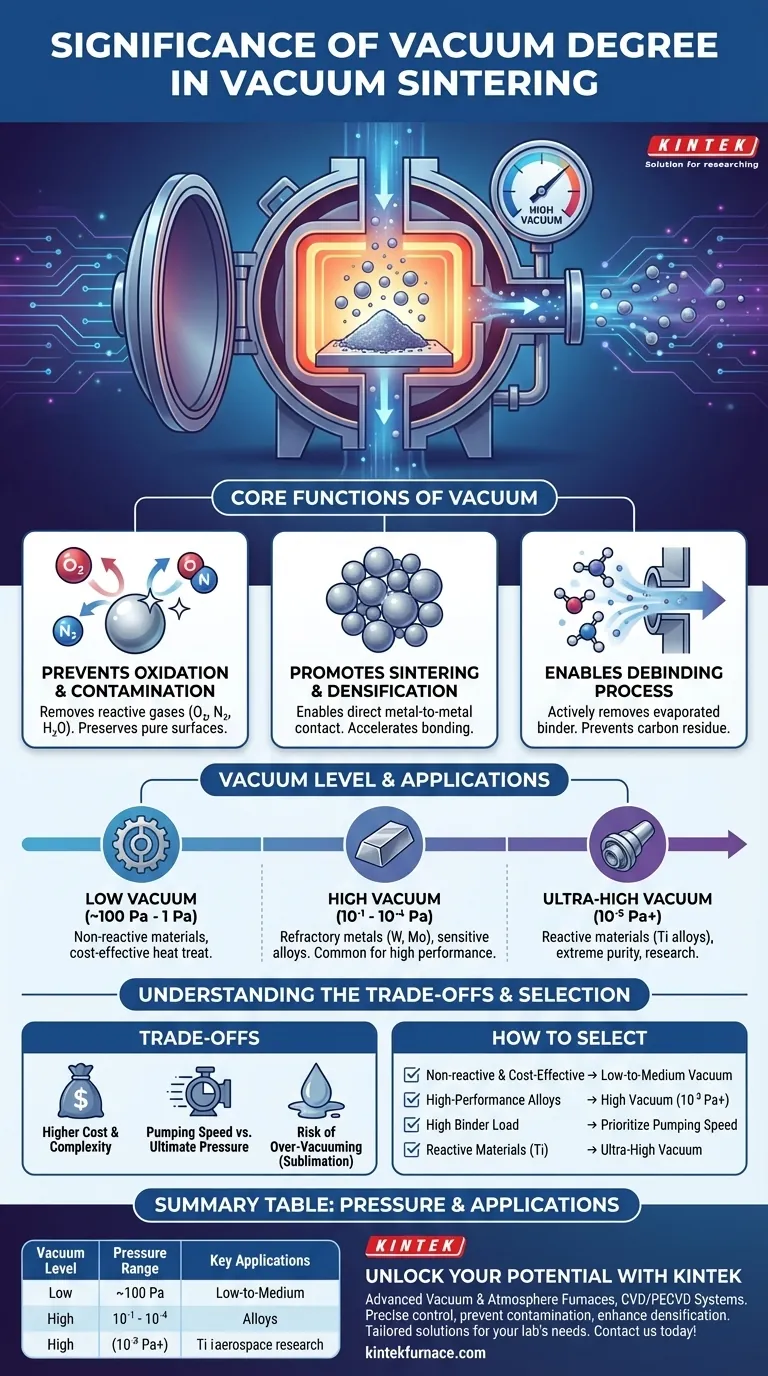

The Core Functions of Vacuum in Sintering

To understand its significance, we must look at the three distinct roles the vacuum environment plays during the sintering process. It is not a passive condition but an active agent in the material's transformation.

Preventing Oxidation and Contamination

At the high temperatures required for sintering, most materials become highly reactive. Any residual oxygen, nitrogen, or water vapor in the furnace will readily react with the material's surface, forming oxides and nitrides.

These unwanted compounds act as a barrier between material particles, inhibiting proper bonding. This results in a final product with lower density, reduced strength, and poor mechanical performance. A high vacuum physically removes these reactive gas molecules, preserving a pure, clean surface on the powder particles.

Promoting Sintering and Densification

The sintering process relies on atoms migrating between particles to form strong metallurgical bonds, closing the gaps between them. This process, known as densification, is most effective on a perfectly clean surface.

By preventing the formation of oxide layers, the vacuum environment ensures that particles are in direct metal-to-metal contact. This dramatically accelerates the sintering reactions, leading to superior densification and enhanced final properties like strength and toughness.

Enabling the Debinding Process

Most powder metallurgy processes use a binder to hold the powder in its "green" shape before sintering. During the initial heating phase, this binder must be completely evaporated and removed.

The vacuum system is responsible for actively pumping out these evaporated binder substances. A furnace's ability to handle this high volume of gas (its pumping speed) is just as important as the ultimate pressure it can reach. Ineffective binder removal will leave behind contaminants like carbon, compromising the material's integrity.

Matching Vacuum Level to Material Requirements

Vacuum furnaces are generally categorized by the level of vacuum they can achieve. The correct choice depends entirely on the sensitivity of the material you are working with.

Low Vacuum (Approx. 100 Pa to 1 Pa)

This level is suitable for sintering less-reactive materials or for general heat treatment processes where a slight amount of surface oxidation is not critical. It provides basic protection from gross oxidation but is insufficient for sensitive alloys.

High Vacuum (10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁴ Pa)

This is the most common range for demanding industrial applications. It is essential for sintering refractory metals like tungsten and molybdenum, as well as other sensitive alloys that are easily embrittled by oxygen or nitrogen. A high vacuum is required to achieve the purity needed for high-performance components.

Ultra-High Vacuum (10⁻⁵ Pa and beyond)

This level is reserved for the most reactive materials, such as titanium alloys, or for cutting-edge research applications where extreme purity is paramount. Achieving and maintaining this level of vacuum requires specialized equipment and is used when even trace amounts of gaseous contaminants are unacceptable.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Selecting a vacuum level is a balance of technical requirements and practical constraints. Simply aiming for the highest possible vacuum is not always the best or most efficient strategy.

The Cost of Higher Vacuum

Achieving a higher vacuum degree is exponentially more difficult. It requires more sophisticated and expensive pumping systems (e.g., turbomolecular or diffusion pumps), longer cycle times to pump down the chamber, and more robust furnace construction to minimize microscopic leaks.

Pumping Speed vs. Ultimate Pressure

It is critical to distinguish between ultimate pressure (the vacuum degree) and pumping speed. Ultimate pressure is how empty the chamber can get, while pumping speed is how fast gas can be removed. A process with significant outgassing from binders requires high pumping speed to stay ahead of contamination, even if the final required vacuum degree is only moderate.

The Risk of Over-Vacuuming

For certain alloys, an excessively high vacuum can be detrimental. Some elements with high vapor pressure (like manganese or zinc) can begin to "boil off" or evaporate from the material at high temperatures under a very hard vacuum. This phenomenon, known as sublimation, can alter the alloy's chemical composition and negatively impact its performance.

How to Select the Right Vacuum Degree

Your choice should be guided by your material and your final goal. The vacuum level is a controllable process variable that must be tailored to your specific application.

- If your primary focus is cost-effective sintering of non-reactive materials: A low-to-medium vacuum furnace often provides the best balance of performance and operational cost.

- If your primary focus is producing high-performance refractory metals or sensitive alloys: A high-vacuum system (10⁻³ Pa or better) is non-negotiable to prevent embrittlement from contamination.

- If your primary focus is removing large amounts of binder during debinding: Prioritize a system with high pumping speed, not just a low ultimate pressure, to handle the high gas load effectively.

- If your primary focus is research or sintering highly reactive materials like titanium: An ultra-high vacuum system is necessary to achieve the purity and material properties required for critical applications.

Ultimately, treating the vacuum degree as a precise process input, not just a furnace setting, is the key to achieving consistent and high-quality results in vacuum sintering.

Summary Table:

| Vacuum Level | Pressure Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Low Vacuum | ~100 Pa to 1 Pa | Non-reactive materials, cost-effective sintering |

| High Vacuum | 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁴ Pa | Refractory metals (e.g., tungsten, molybdenum), sensitive alloys |

| Ultra-High Vacuum | 10⁻⁵ Pa and beyond | Reactive materials (e.g., titanium alloys), high-purity research |

Unlock the Full Potential of Your Sintering Process with KINTEK

Struggling to achieve the right vacuum degree for your materials? KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnace solutions, including Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces and CVD/PECVD Systems, are engineered to deliver precise vacuum control, prevent contamination, and enhance densification. With our exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we offer deep customization to meet your unique experimental needs—whether you're sintering refractory metals, sensitive alloys, or handling reactive materials. Don't let vacuum challenges hold you back; contact us today to discuss how our tailored solutions can boost your lab's efficiency and material performance!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What role does a vacuum hot pressing furnace play in TiBw/TA15 synthesis? Enhance In-Situ Composite Performance

- How do vacuum sintering and annealing furnaces contribute to the densification of NdFeB magnets?

- Why is a vacuum hot press sintering furnace required for nanocrystalline ceramics? Preserve Structure with Pressure

- Why is a vacuum environment essential for sintering Titanium? Ensure High Purity and Eliminate Brittleness

- What is the function of a vacuum sintering furnace in CoNiCrAlY coatings? Repairing Cold-Sprayed Microstructures