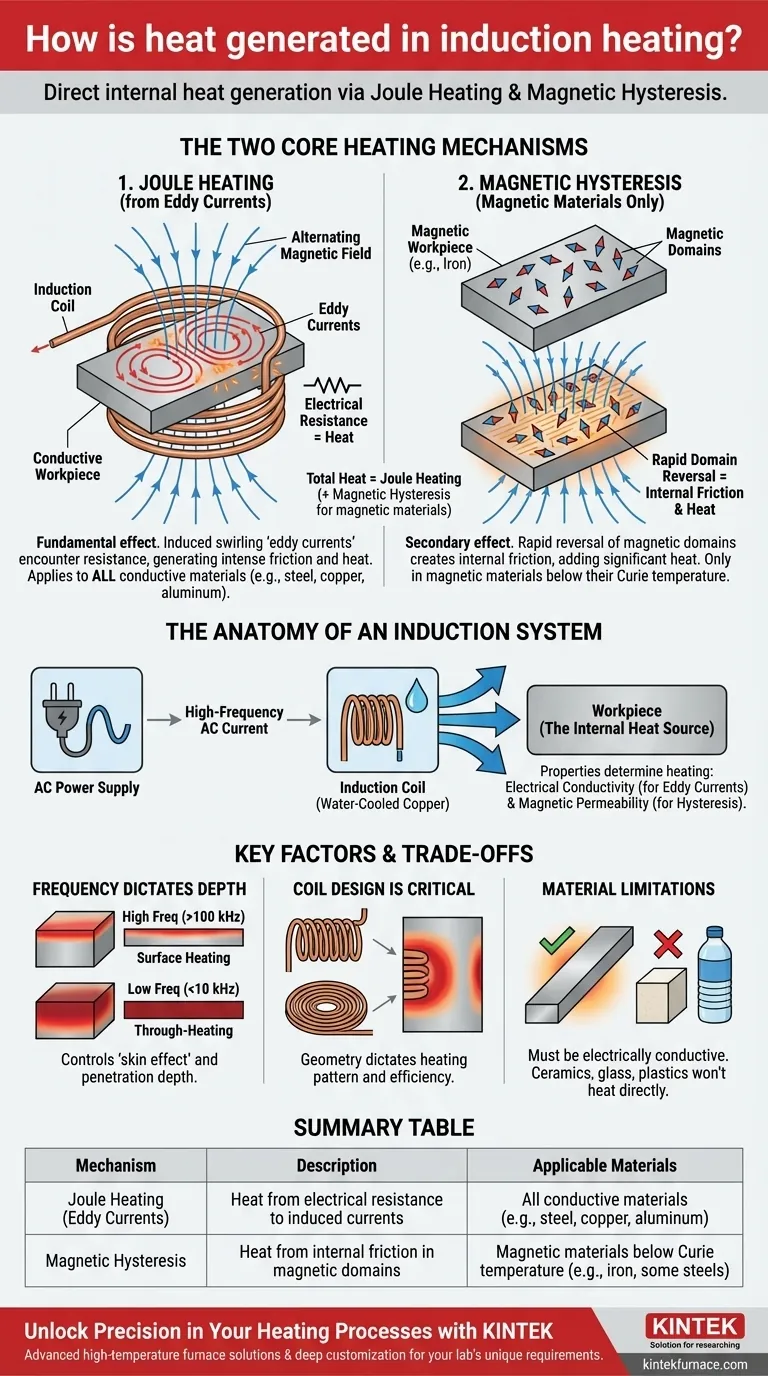

In essence, induction heating generates heat directly within a conductive material using two primary physical phenomena. The primary mechanism is Joule heating, caused by induced electrical currents called "eddy currents." For magnetic materials like iron, a secondary mechanism called magnetic hysteresis also contributes significant heat.

The core principle of induction heating is not the application of external heat, but the use of a non-contact, rapidly alternating magnetic field to turn the workpiece into its own internal heat source. The process is governed by the material's electrical and magnetic properties.

The Two Core Heating Mechanisms

To understand how induction works, you must grasp the two distinct ways it generates heat inside a material. One is always present in conductive materials, while the other is a bonus that occurs only in magnetic ones.

Mechanism 1: Joule Heating (from Eddy Currents)

This is the fundamental effect responsible for all induction heating. The process follows from Faraday's Law of Induction.

First, an induction coil generates a strong, rapidly alternating magnetic field. When you place an electrically conductive workpiece (like steel, copper, or aluminum) into this field, the field induces circulating electrical currents within the part.

These localized, swirling currents are known as eddy currents.

As these eddy currents flow through the material, they encounter electrical resistance. This resistance to the flow of electrons generates friction and, therefore, intense heat. This phenomenon is known as Joule heating or resistive heating. The amount of heat is directly proportional to the material's resistance and the square of the current.

Mechanism 2: Magnetic Hysteresis (Magnetic Materials Only)

This secondary heating effect only occurs in magnetic materials, such as iron and certain types of steel, when they are below their Curie temperature (the point at which they lose their magnetic properties).

Magnetic materials are composed of tiny magnetic "domains." When exposed to the alternating magnetic field from the induction coil, these domains rapidly flip their polarity to align with the field, billions of times per second.

This rapid, forced reversal of the magnetic domains creates a great deal of internal friction. This friction manifests as heat, adding to the heat already being generated by the eddy currents. This makes heating magnetic materials below their Curie point exceptionally fast and efficient.

The Anatomy of an Induction System

These physical principles are put into practice by a system of carefully engineered components, each with a specific role.

The Power Supply and Induction Coil

The entire process begins with a specialized AC power supply that converts standard line frequency into a high-frequency alternating current. This current is then sent to the induction coil.

The coil, typically made of water-cooled copper tubing, does not touch the workpiece. Its job is simply to generate the powerful, alternating magnetic field that serves as the energy transfer medium.

The Workpiece Properties

The workpiece itself is a critical part of the circuit. Its properties determine how effectively it can be heated.

Electrical conductivity is required for eddy currents to be induced. Magnetic permeability determines whether additional heat can be generated through hysteresis.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Key Factors

The effectiveness and precision of induction heating are not automatic. They depend entirely on controlling a few key variables.

Frequency Dictates Heating Depth

The frequency of the alternating current is one of the most critical parameters. It controls the "skin effect," which dictates how deeply the heat penetrates the part.

- High Frequencies (e.g., >100 kHz): The current flows in a thin layer near the surface of the part, resulting in shallow, precise surface heating.

- Low Frequencies (e.g., <10 kHz): The current penetrates deeper into the part, resulting in more uniform, through-heating.

Coil Design Is Everything

The design of the induction coil—its shape, size, and proximity to the workpiece—is paramount. The magnetic field is strongest closest to the coil, so the coil's geometry directly dictates the heating pattern.

A poorly designed or positioned coil will result in inefficient energy transfer and uneven heating, failing to achieve the desired outcome.

Material Limitations

Induction heating only works on materials that are electrically conductive. Materials like ceramics, glass, or most plastics cannot be heated directly with this method because they cannot support the flow of eddy currents.

Applying This to Your Goal

Your choice of frequency and system design should be driven by your specific heating objective.

- If your primary focus is surface hardening: Use a high-frequency system and a precisely shaped coil that is closely coupled to the part for shallow, rapid heating.

- If your primary focus is through-heating for forging or melting: Use a lower-frequency system to ensure the magnetic field and resulting heat penetrate deep into the material's core.

- If your primary focus is heating non-magnetic conductors (e.g., aluminum, copper): Rely entirely on generating strong eddy currents for Joule heating, as you will get no contribution from magnetic hysteresis.

Ultimately, mastering induction heating lies in understanding that you are not applying external heat, but generating it precisely where needed by controlling an invisible magnetic field.

Summary Table:

| Mechanism | Description | Applicable Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Joule Heating (Eddy Currents) | Heat from electrical resistance to induced currents | All conductive materials (e.g., steel, copper, aluminum) |

| Magnetic Hysteresis | Heat from internal friction in magnetic domains | Magnetic materials below Curie temperature (e.g., iron, some steels) |

Unlock Precision in Your Heating Processes with KINTEK

Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, KINTEK provides diverse laboratories with advanced high-temperature furnace solutions. Our product line, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems, is complemented by our strong deep customization capability to precisely meet unique experimental requirements. Whether you need surface hardening, through-heating, or specialized setups for conductive materials, our expertise ensures optimal performance and efficiency.

Contact us today to discuss how our tailored induction heating solutions can enhance your lab's capabilities and drive your research forward!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the function of a vacuum sintering furnace in the SAGBD process? Optimize Magnetic Coercivity and Performance

- What processing conditions does a vacuum furnace provide for TiCp/Fe microspheres? Sintering at 900 °C

- What is the role of sintering or vacuum induction furnaces in battery regeneration? Optimize Cathode Recovery

- Why must sintering equipment maintain a high vacuum for high-entropy carbides? Ensure Phase Purity and Peak Density

- What is the purpose of performing medium vacuum annealing on working ampoules? Ensure Pure High-Temp Diffusion