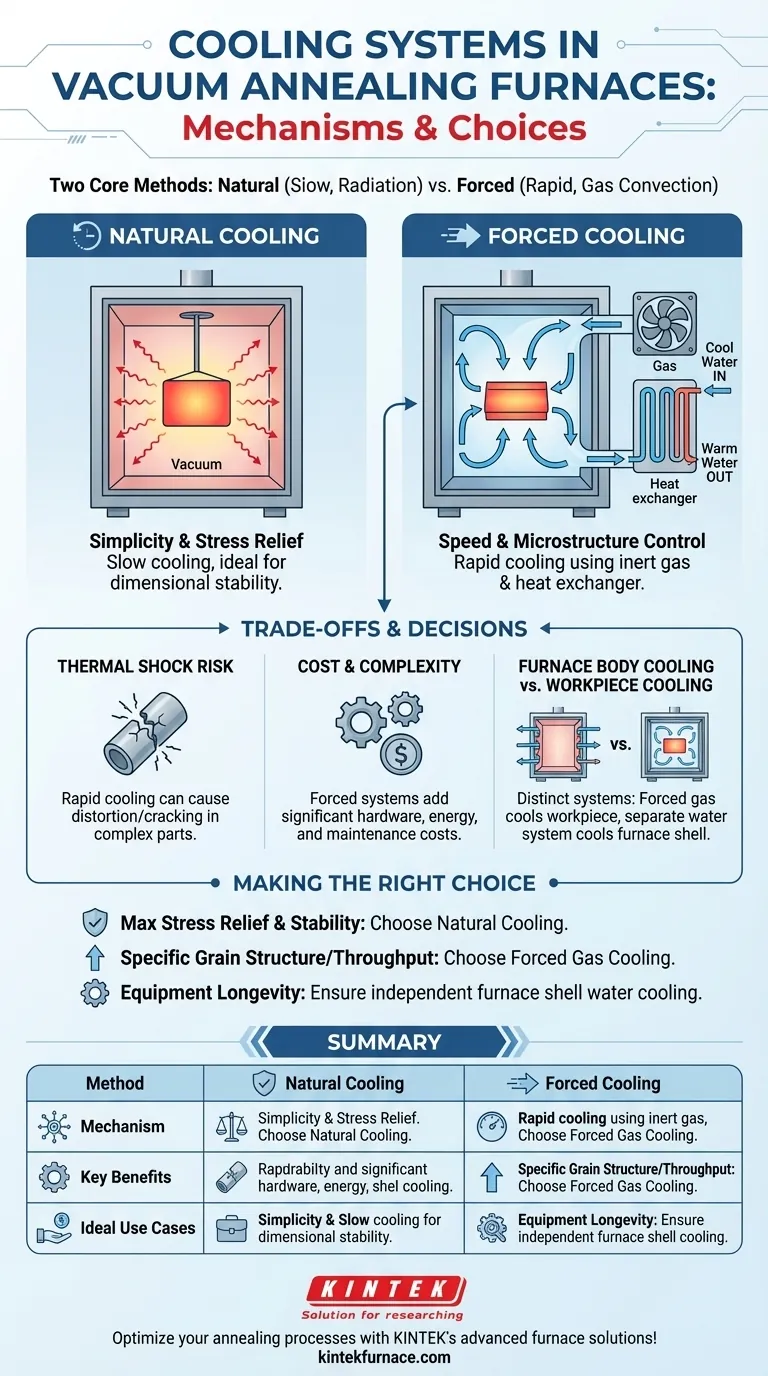

At its core, a vacuum annealing furnace cools a workpiece using one of two methods: slowly, by simply letting it radiate heat away in the vacuum (natural cooling), or rapidly, by introducing an inert gas and circulating it at high speed through a heat exchanger (forced cooling). The forced cooling system uses a powerful fan to move the gas over the hot workpiece and then through a water-cooled heat exchanger to remove the thermal energy.

The choice between slow, natural cooling and rapid, forced cooling is not merely a matter of process time. It is a fundamental decision that directly dictates the final metallurgical properties of the material, such as its internal stress, grain structure, and hardness.

The Two Primary Cooling Philosophies

In vacuum annealing, cooling is as critical as heating. The method chosen determines the final state of the workpiece after the thermal cycle is complete.

Natural Cooling: Simplicity and Stress Relief

Natural cooling is the most straightforward method. After the heating and soaking stages are complete, the heating elements are simply turned off.

The workpiece then cools slowly inside the furnace chamber. The vacuum acts as an excellent insulator, meaning heat can only escape via radiation, a much slower process than convection. This slow, gentle cooling is ideal for maximizing stress relief and ensuring high dimensional stability.

Forced Cooling: Speed and Microstructure Control

Forced cooling is an active process designed for rapid temperature reduction. It involves backfilling the evacuated furnace chamber with a high-purity inert gas, such as nitrogen or argon.

This gas provides a medium for convective heat transfer, which is far more efficient than radiation alone. This method is used when specific material properties must be "locked in" by a faster quench or when production throughput is a primary concern.

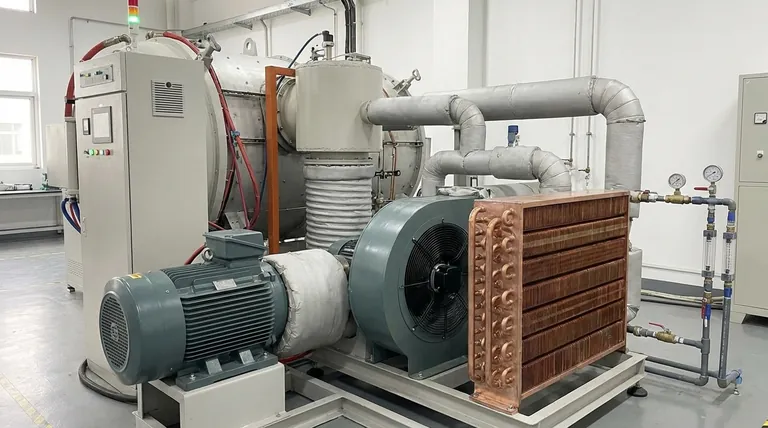

Anatomy of a Forced Gas Cooling System

A forced cooling system is a closed-loop circuit designed to move heat from the workpiece to an external medium as efficiently as possible.

The Inert Gas Medium

A vacuum is an insulator, so to cool a part quickly, you must introduce a gas to transfer the heat. Inert gases like nitrogen or argon are used because they will not react with or contaminate the hot workpiece surface.

The High-Power Fan and Motor

The heart of the system is a high-power motor driving a high-pressure fan or impeller. This is the engine that vigorously circulates the inert gas throughout the furnace chamber at high velocity.

The Heat Exchanger

The heat exchanger is where the heat is actually removed from the system. As the hot gas is pulled away from the workpiece, it is forced through a radiator-like device, typically made of copper tubes and fins.

Cool water circulates through these tubes, absorbing the thermal energy from the gas. The now-cooled gas is then ready to be recirculated back to the workpiece.

The Gas Circulation Path

The components work in a continuous, high-speed loop. The fan pushes cool gas from the heat exchanger through guide vanes that direct it uniformly onto the workpiece. The gas absorbs heat, flows away from the part, and is pulled back into the fan to be pushed through the heat exchanger again.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing a cooling method involves balancing metallurgical goals against process complexity and cost. There is no single "best" method; the correct choice depends entirely on the desired outcome for the material.

Furnace Body Cooling vs. Workpiece Cooling

It is critical to distinguish between two separate water-cooling functions. The forced gas cooling system uses water in its heat exchanger to cool the workpiece.

Separately, a furnace water cooling system circulates water through the furnace shell, doors, and seals. This system runs continuously to protect the equipment from overheating and to help maintain the high vacuum required for the process.

The Risk of Thermal Shock

The primary downside of rapid forced cooling is the potential for introducing thermal stress or shock into the workpiece. If the part has complex geometry with thick and thin sections, rapid cooling can cause it to distort or even crack.

Cost and Complexity

Natural cooling requires no extra hardware. A forced cooling system adds significant complexity and cost, including a powerful motor, a large fan, a gas heat exchanger, and the associated plumbing and control systems. This also increases energy consumption and maintenance requirements.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your decision on a cooling strategy must be driven by the end-use requirements of the component being annealed.

- If your primary focus is maximum stress relief and dimensional stability: Use natural (vacuum) cooling, as its slow rate minimizes the introduction of new thermal gradients and internal stresses.

- If your primary focus is achieving a specific grain structure or increasing throughput: Use forced gas cooling to rapidly lower the temperature and control the final metallurgical phase of the material.

- If your primary focus is equipment longevity and process consistency: Ensure the furnace's independent water cooling system for the shell and seals is properly maintained, as this protects the entire investment regardless of the workpiece cooling method.

Ultimately, mastering the cooling phase is essential for leveraging the full potential of the vacuum annealing process.

Summary Table:

| Cooling Method | Mechanism | Key Benefits | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Cooling | Heat radiates in vacuum | Stress relief, dimensional stability | Maximizing material stability |

| Forced Cooling | Inert gas circulated with fan and heat exchanger | Rapid cooling, microstructure control | High throughput, specific metallurgical properties |

Optimize your annealing processes with KINTEK's advanced furnace solutions! Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with tailored high-temperature furnace systems, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures precise alignment with your unique experimental needs for enhanced efficiency and results. Contact us today to discuss how we can support your goals!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What tasks does a high-temperature vacuum sintering furnace perform for PEM magnets? Achieve Peak Density

- What is the role of vacuum pumps in a vacuum heat treatment furnace? Unlock Superior Metallurgy with Controlled Environments

- Why is a vacuum environment essential for sintering Titanium? Ensure High Purity and Eliminate Brittleness

- How does the ultra-low oxygen environment of vacuum sintering affect titanium composites? Unlock Advanced Phase Control

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion