At its core, cooling systems in vacuum furnaces serve two distinct and equally critical functions. They are essential for protecting the furnace structure itself from extreme operational temperatures, and, more importantly, they are a primary tool for precisely controlling the cooling of the processed material to achieve specific, desired metallurgical properties.

The cooling system is not an auxiliary component; it is a fundamental instrument of control. The rate and uniformity of cooling are as critical as the heating cycle, directly determining the final strength, hardness, and internal structure of the material being treated.

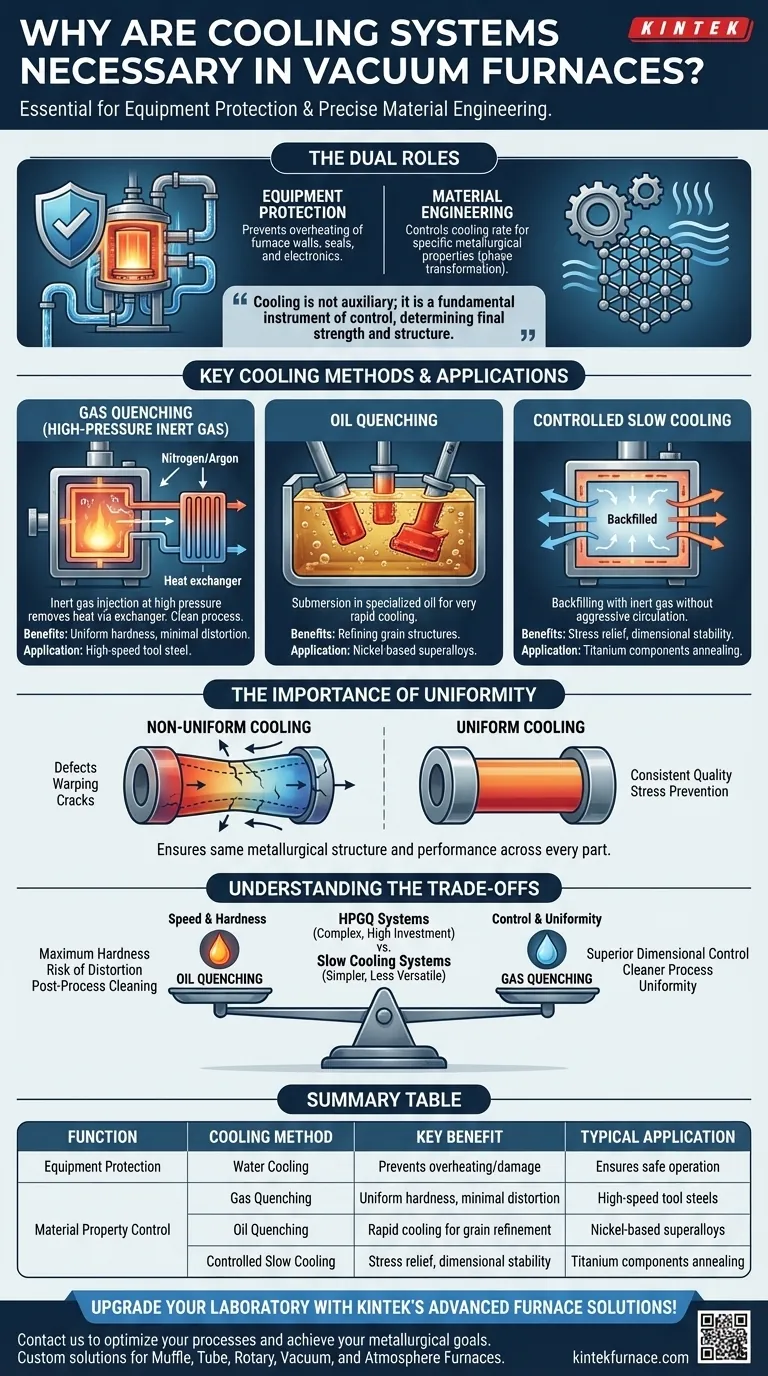

The Dual Roles of a Vacuum Furnace Cooling System

We can separate the function of a cooling system into two main categories: protecting the equipment and engineering the final product.

Protecting Furnace Integrity

A vacuum furnace operates at temperatures that can easily damage its own structure. A robust cooling system, typically using circulating water in the furnace walls or shell, is the first line of defense.

This cooling prevents the outer body, seals, power connections, and control electronics from overheating, ensuring safe operation and protecting the significant capital investment the furnace represents.

Engineering the Material's Final Properties

This is the metallurgical purpose of the cooling system. The speed at which a metal cools from a high temperature directly dictates its final microstructure through a process called phase transformation.

By precisely managing the cooling rate, an operator can lock in specific material characteristics. Rapid cooling, or quenching, can create a very hard structure, while slow, controlled cooling can relieve internal stress and increase ductility.

Key Cooling Methods and Their Applications

The choice of cooling method is determined by the material being treated and the desired outcome. The three primary methods offer different levels of speed and control.

Gas Quenching (High-Pressure Inert Gas)

In this method, an inert gas like high-purity nitrogen or argon is injected into the hot zone, often at high pressure (two or more times atmospheric pressure).

The gas circulates through the workload, absorbs heat, and is then passed through a heat exchanger to remove the thermal energy. This is a clean process ideal for materials like high-speed tool steel, where it achieves uniform hardness with minimal distortion.

Oil Quenching

For some alloys, particularly certain nickel-based superalloys, the cooling rates required to achieve the desired properties are faster than even high-pressure gas can provide.

In these cases, the hot material is submerged in a specialized oil bath for very rapid cooling. This method is highly effective for tasks like refining grain structures but can introduce more thermal stress and requires post-process cleaning of the parts.

Controlled Slow Cooling

Not all heat treatment processes require rapid cooling. For applications like stress-relief annealing of titanium components, the goal is to cool the material slowly and uniformly.

This is achieved by backfilling the chamber with an inert gas without aggressive circulation, allowing heat to dissipate gradually. This prevents the formation of internal stresses that could lead to part failure under load.

The Critical Importance of Cooling Uniformity

Whether cooling fast or slow, uniformity is paramount. Non-uniform cooling is a primary cause of defects and inconsistent quality.

Preventing Stress and Distortion

If one section of a part cools faster than another, it contracts at a different rate. This differential creates powerful internal stresses that can warp the component or, in severe cases, cause microscopic or even visible cracks.

Ensuring Consistent Performance

Uniform cooling ensures that every part in a batch—and every section of a single part—has the same metallurgical structure and, therefore, the same performance characteristics. This consistency is non-negotiable for high-stress applications in the aerospace, automotive, or medical industries.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Selecting a cooling method involves balancing speed, control, and complexity. No single method is universally superior.

Speed vs. Control

Faster quenching isn't always better. Aggressive cooling methods like oil quenching achieve maximum hardness but carry a higher risk of introducing internal stress and distortion. Slower gas quenching offers superior dimensional control and uniformity.

Gas vs. Liquid Quenching

Gas quenching is a much cleaner process, avoiding the need for part washing and waste oil disposal. However, liquid quenching can achieve much higher cooling rates when required by the material's specific metallurgy.

Cost and Complexity

Systems capable of high-pressure gas quenching (HPGQ) with optimized nozzle design are complex and represent a significant investment. Simpler systems for slow, controlled cooling are less expensive but lack the versatility to process a wide range of advanced alloys.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The optimal cooling strategy is defined by the material and your final objective.

- If your primary focus is maximum hardness in tool steels: High-pressure gas quenching is the modern standard for achieving uniform hardness with excellent dimensional control.

- If your primary focus is grain refinement in specific superalloys: Rapid oil quenching is often necessary to achieve the required cooling rates, accepting the trade-offs of potential distortion and post-process cleaning.

- If your primary focus is stress relief and dimensional stability: Controlled, slow cooling using an inert gas backfill is the ideal and most reliable method.

- If your primary focus is operational safety and equipment longevity: A robust, independent water-cooling system for the furnace chamber and body is a non-negotiable foundation for any process.

Ultimately, the cooling system transforms the vacuum furnace from a simple oven into a precise metallurgical instrument.

Summary Table:

| Function | Cooling Method | Key Benefit | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment Protection | Water Cooling | Prevents overheating and damage | Ensures safe operation and longevity |

| Material Property Control | Gas Quenching | Uniform hardness with minimal distortion | High-speed tool steels |

| Material Property Control | Oil Quenching | Rapid cooling for grain refinement | Nickel-based superalloys |

| Material Property Control | Controlled Slow Cooling | Stress relief and dimensional stability | Titanium components annealing |

Upgrade your laboratory's capabilities with KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnace solutions! Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with precision-engineered products like Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we can precisely meet your unique experimental requirements, delivering superior performance and reliability. Don't let cooling challenges hold you back—contact us today to discuss how we can optimize your processes and achieve your metallurgical goals!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- High Pressure Laboratory Vacuum Tube Furnace Quartz Tubular Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

People Also Ask

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in LP-DED? Optimize Alloy Integrity Today

- What are the proper procedures for handling the furnace door and samples in a vacuum furnace? Ensure Process Integrity & Safety

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- What are the components of a vacuum furnace? Unlock the Secrets of High-Temperature Processing