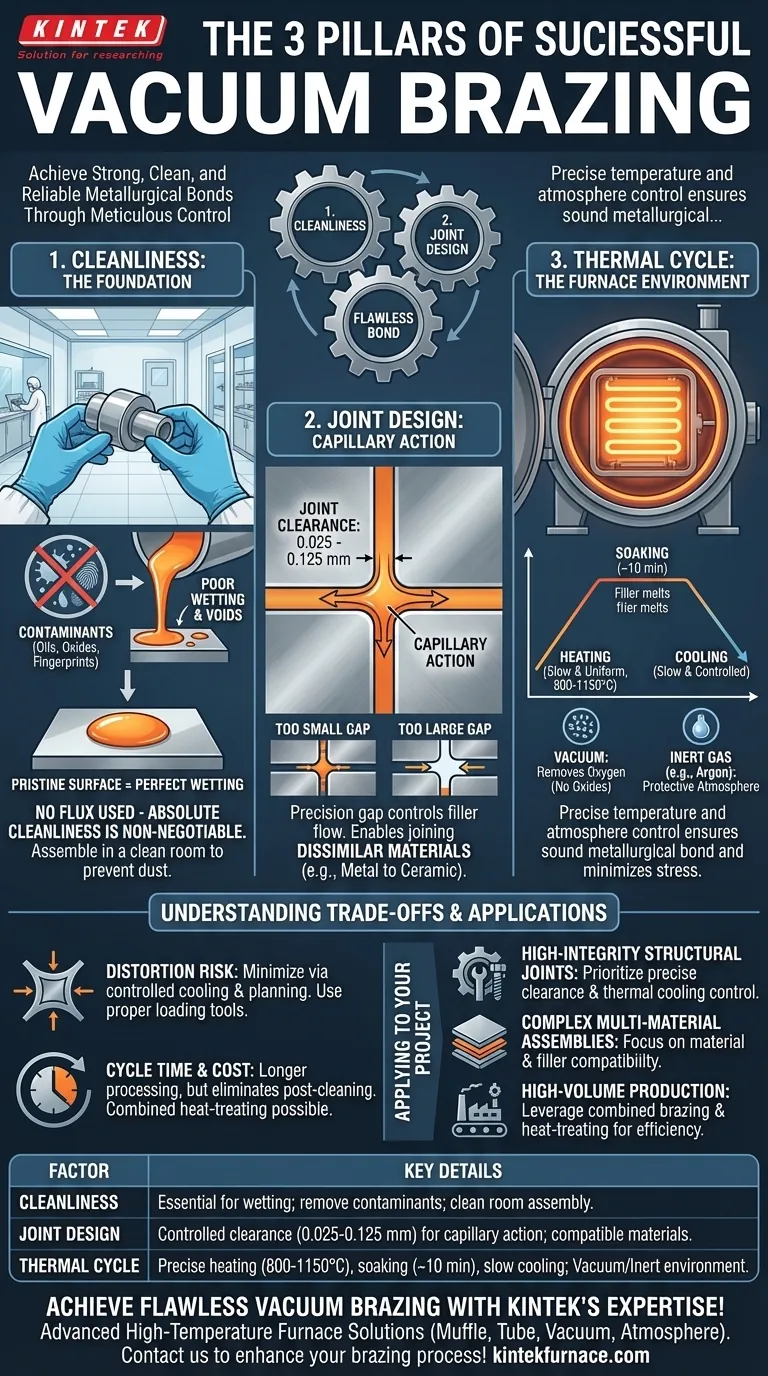

To achieve a successful vacuum braze, you must meticulously control three core areas: the pre-braze cleanliness of the components, the physical design of the joint itself, and the precise thermal cycle within the vacuum furnace. These elements work in concert to create an environment where a strong, clean, and reliable metallurgical bond can form without defects.

The success of vacuum brazing is not determined by a single factor, but by a holistic system of control. It is a process of creating a pristine, oxygen-free environment where precise temperature control and joint design allow the filler metal to bond with the parent materials perfectly.

The Foundation: Preparation and Cleanliness

The most common point of failure in vacuum brazing occurs before the parts ever enter the furnace. Absolute cleanliness is non-negotiable.

Why Contaminants Are the Enemy

Contaminants like oils, greases, oxides, and even fingerprints act as a barrier. They prevent the molten brazing filler metal from "wetting" and flowing evenly across the parent metal surfaces.

This results in voids, incomplete joints, and a dramatically weaker bond. Because vacuum brazing does not use flux to chemically clean surfaces during heating, the initial cleanliness is the only thing ensuring a proper bond.

The Role of a Clean Environment

Your control over cleanliness must extend beyond the parts themselves. Assembling components in a dedicated, clean room is critical.

This practice prevents dust, fibers, and other airborne particles from settling on the prepared parts or the filler metal before they are loaded into the furnace.

Mastering the Brazing Environment: The Furnace

The vacuum furnace is where the joining occurs. Controlling the atmosphere and temperature profile is the key to creating a flawless joint.

Achieving the Necessary Vacuum

The primary purpose of the vacuum is to remove oxygen and other reactive gases. This prevents the formation of oxides on the metal surfaces as they are heated.

Without oxides, the filler metal can interact directly with the parent materials, resulting in a bright, clean, and metallurgically sound joint. For some applications, the chamber is backfilled with an inert gas like argon to provide a protective atmosphere.

The Thermal Cycle: A Precise Recipe

The thermal cycle is the specific heating, soaking, and cooling profile for the assembly.

- Heating: Parts are heated slowly and uniformly to the brazing temperature, which is typically between 800°C and 1150°C. This slow ramp-up minimizes thermal stress and distortion.

- Soaking: The assembly is held at the brazing temperature for a short period, often around 10 minutes, allowing the filler metal to melt and flow completely throughout the joint.

- Cooling: Slow, controlled cooling is essential to reduce residual stresses and prevent cracking, preserving the integrity of the final assembly.

Designing for Success: Joint and Material Considerations

A perfect process cannot fix a poorly designed part. The physical design of the joint is just as critical as the furnace environment.

The Critical Role of Joint Clearance

Vacuum brazing relies on capillary action to pull the molten filler metal into the gap between the parts. The gap, or joint clearance, must be precisely controlled.

A typical clearance is between 0.025 mm and 0.125 mm. If the gap is too small, the filler metal cannot flow in; if it is too large, capillary action will fail and the joint will be weak or incomplete.

Selecting the Right Materials

Careful selection of both the parent metals and the brazing filler alloy is essential. The materials must be compatible with each other and with the intended thermal cycle.

This process excels at joining dissimilar materials, such as metals to ceramics, which is a key advantage over other joining methods. The filler metal's melting point must be lower than that of the parent materials.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While powerful, vacuum brazing has practical limitations and requires an understanding of its inherent trade-offs.

The Risk of Distortion

While controlled cooling significantly minimizes stress, the high temperatures involved mean that the risk of distortion is never zero. Complex geometries or assemblies with very different material thicknesses require careful planning and appropriate loading tools to support the parts.

Cycle Time and Cost

Vacuum brazing is not an instantaneous process. The need to pump down a vacuum and execute slow heating and cooling cycles results in longer processing times compared to other methods.

While it can be cost-effective by eliminating post-braze cleaning and enabling combined heat-treating cycles, the initial equipment investment and cycle time are important considerations.

Process Control Is Absolute

There is little room for error. A failure in cleanliness, a poorly designed joint, or an incorrect thermal profile often means the entire part must be scrapped. The process demands rigorous control and post-braze inspection and testing to ensure quality.

Applying This to Your Project

Your focus should be guided by the primary goal of your specific application.

- If your primary focus is high-integrity structural joints: Prioritize precise joint clearance and meticulous control over the thermal cooling cycle to minimize residual stress.

- If your primary focus is complex, multi-material assemblies: Concentrate on the compatibility between parent materials and the filler alloy to ensure a strong metallurgical bond.

- If your primary focus is high-volume production: Leverage the ability to combine brazing with heat-treating and age-hardening in a single furnace cycle to maximize efficiency.

Ultimately, successful vacuum brazing is achieved by viewing it as an integrated system where every step, from design to final inspection, is critically important.

Summary Table:

| Factor | Key Details |

|---|---|

| Cleanliness | Essential for filler metal wetting; requires oil, grease, and oxide removal; assembly in clean room to prevent contaminants. |

| Joint Design | Controlled clearance (0.025-0.125 mm) for capillary action; compatible materials for dissimilar joining. |

| Thermal Cycle | Precise heating (800-1150°C), soaking (~10 min), and slow cooling to minimize stress and ensure proper bonding. |

| Vacuum Environment | Removes oxygen to prevent oxides; may use inert gases like argon for protection. |

Achieve flawless vacuum brazing with KINTEK's expertise! Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide advanced high-temperature furnace solutions like Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our deep customization capability ensures precise alignment with your unique experimental needs, whether for high-integrity structural joints, complex multi-material assemblies, or high-volume production. Contact us today to discuss how our tailored solutions can enhance your brazing process and deliver reliable results!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- Why is a high-vacuum environment necessary for sintering Cu/Ti3SiC2/C/MWCNTs composites? Achieve Material Purity

- What is the role of vacuum pumps in a vacuum heat treatment furnace? Unlock Superior Metallurgy with Controlled Environments

- Why is a vacuum environment essential for sintering Titanium? Ensure High Purity and Eliminate Brittleness

- What are the benefits of using a high-temperature vacuum furnace for the annealing of ZnSeO3 nanocrystals?