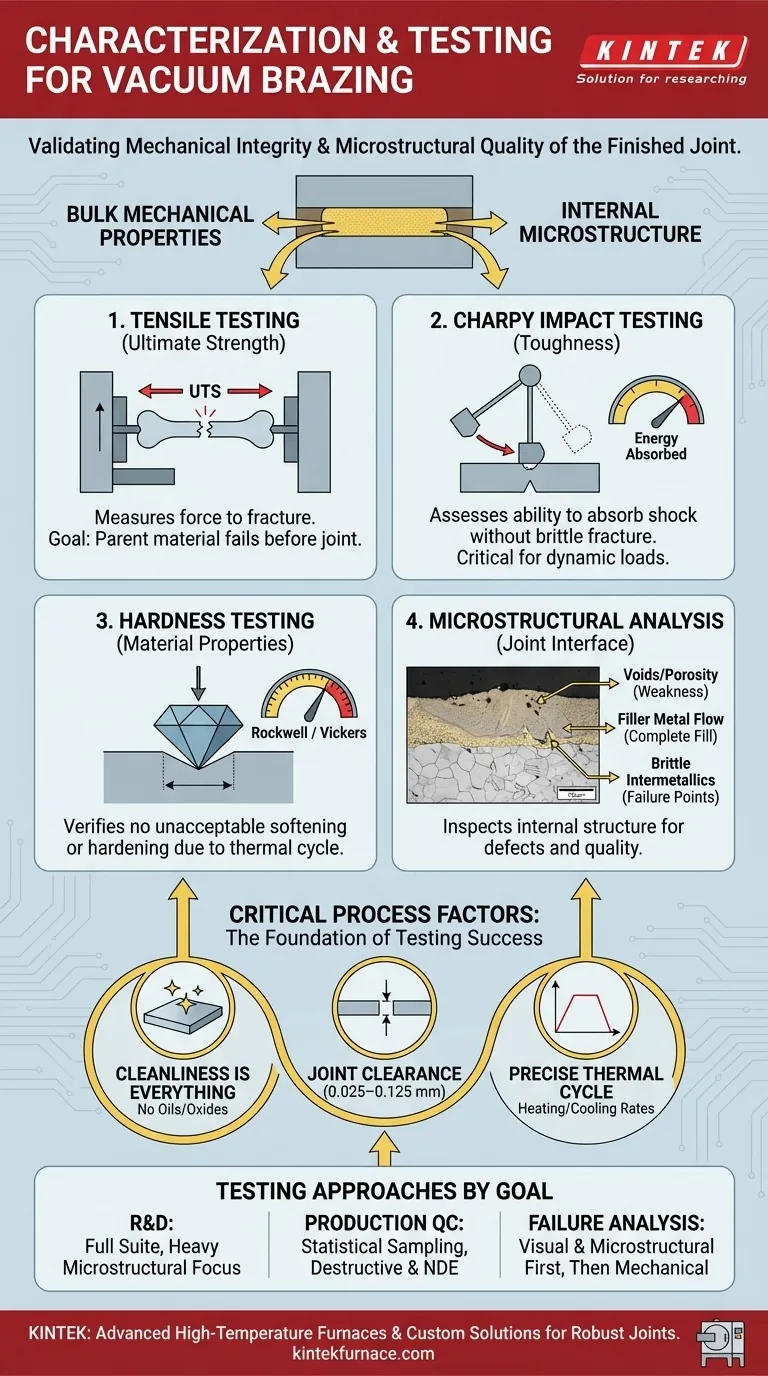

For vacuum brazing, the primary characterization and testing facilities are used to validate the mechanical integrity and microstructural quality of the finished joint. This involves a combination of destructive tests that measure strength and toughness, including tensile testing, Charpy impact testing, and both macro and micro hardness testing. These methods ensure that the brazed component meets the precise engineering specifications required for its application, verifying that the joining process has not introduced any weaknesses or unintended material changes.

The core issue is not simply listing test equipment, but understanding that testing is the final, critical validation in a process where success is determined long before the part enters the furnace. Effective testing confirms that meticulous control over joint design, cleanliness, and the thermal cycle has produced a reliable and robust component.

Why Testing is a Pillar of Successful Brazing

Vacuum brazing is often employed in high-stakes industries like aerospace, medical, and energy, where component failure can have severe consequences. Testing is not merely a quality check; it is an essential part of process development, certification, and ongoing quality assurance.

The Demands of Critical Applications

Applications such as gas turbine engines, fuel and hydraulic systems, and satellite components rely on vacuum brazing for its ability to create strong, leak-tight joints with minimal distortion. These components must withstand extreme temperatures, pressures, and vibrations. Testing provides the objective proof that the brazed joint can survive these service conditions.

From Process Development to Production Control

During research and development, a full suite of tests helps engineers optimize parameters like furnace temperature, hold times, and filler alloy selection. For production, a strategic selection of these tests on a statistical basis ensures the process remains stable and continues to produce parts that meet the original, validated standard.

Key Characterization and Testing Methods

The required tests can be broken down into those that measure the bulk mechanical properties of the joint and those that inspect its internal structure at a microscopic level.

Tensile Testing: Measuring Ultimate Strength

A tensile test involves pulling a sample of the brazed joint apart until it breaks. This directly measures the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of the joint. The goal is often for the parent material to fail before the braze joint does, proving the joint is not the weakest link in the assembly.

Charpy Impact Testing: Assessing Toughness

The Charpy test measures a material's ability to absorb a sudden shock or impact load without fracturing. A pendulum strikes a notched sample of the brazed joint, and the energy absorbed during fracture indicates its toughness. This is critical for components that may experience dynamic forces or operate at low temperatures where materials can become brittle.

Hardness Testing: Verifying Material Properties

The thermal cycle of brazing can alter the hardness—and therefore the strength and wear resistance—of the parent materials near the joint. Hardness testing, using methods like Rockwell or Vickers, presses a small indenter into the material. This test verifies that the heat treatment did not unacceptably soften or harden the base materials.

Microstructural Analysis: Inspecting the Joint Interface

This is arguably the most insightful form of testing. A cross-section of the brazed joint is cut, polished, and chemically etched to reveal its internal structure under a microscope. This metallographic analysis can identify:

- Voids or porosity: Gaps that weaken the joint and can cause leaks.

- Filler metal flow: Confirms the alloy has properly filled the entire joint clearance.

- Brittle intermetallics: Undesirable chemical compounds that can form at the interface between the filler and parent material, acting as a common point of failure.

This analysis is often paired with microhardness testing, which uses a very small indenter to measure hardness variations across the microscopic joint interface, precisely identifying brittle zones.

Understanding the Critical Process Factors

No amount of testing can salvage a joint that was destined to fail due to poor preparation or process control. The results from the tests above are direct reflections of how well the preceding steps were managed.

The "Cleanliness is Everything" Principle

Successful vacuum brazing is impossible without immaculately clean parts and assembly environments. Any oils, oxides, or contaminants will prevent the filler metal from properly wetting and adhering to the parent materials, leading to voids and a weak bond that will fail under testing.

The Criticality of Joint Clearance

The gap between the parts being joined—the joint clearance—is a critical design parameter, typically falling between 0.025 mm and 0.125 mm (0.001" to 0.005"). If the gap is too narrow, the filler metal cannot flow in via capillary action. If it is too wide, it will not fill completely, resulting in a weak, porous joint.

The Double-Edged Sword of the Thermal Cycle

The thermal cycle is necessary to melt the braze alloy, but it can also induce stress, cause distortion, or create undesirable metallurgical changes in the parent materials. Precise control of heating rates, hold times, and cooling rates is essential to achieve a strong joint without compromising the integrity of the overall assembly.

How to Approach Testing for Your Project

The specific testing regimen you need depends on your goal.

- If your primary focus is Research and Development: Employ the full suite of tests, with a heavy emphasis on microstructural analysis, to understand how process variables directly impact joint quality at a microscopic level.

- If your primary focus is Production Quality Control: Rely on statistical sampling for destructive tests like tensile pulls, supplemented by non-destructive evaluation (NDE) where applicable, to ensure ongoing process stability.

- If your primary focus is Failure Analysis: Begin with a thorough visual and microstructural analysis to identify the failure mode and origin before using mechanical tests to confirm the root cause.

Ultimately, a robust testing strategy transforms vacuum brazing from a complex art into a reliable and repeatable engineering science.

Summary Table:

| Test Method | Purpose | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Testing | Measures joint strength | Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) |

| Charpy Impact Testing | Assesses toughness under shock | Energy absorbed during fracture |

| Hardness Testing | Verifies material property changes | Rockwell, Vickers hardness values |

| Microstructural Analysis | Inspects joint interface quality | Voids, filler flow, intermetallics |

Need reliable vacuum brazing solutions for your lab? At KINTEK, we leverage exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnaces like Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. With strong deep customization capabilities, we precisely meet your unique experimental requirements—ensuring robust joints for critical applications in aerospace, medical, and energy sectors. Contact us today to enhance your brazing process with tailored support!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the benefits of using a high-temperature vacuum furnace for the annealing of ZnSeO3 nanocrystals?

- What is the purpose of a 1400°C heat treatment for porous tungsten? Essential Steps for Structural Reinforcement

- Why is a high vacuum essential for Ti-6Al-4V sintering? Protect Your Alloys from Embrittlement

- What is the purpose of setting a mid-temperature dwell stage? Eliminate Defects in Vacuum Sintering

- What is the role of vacuum pumps in a vacuum heat treatment furnace? Unlock Superior Metallurgy with Controlled Environments