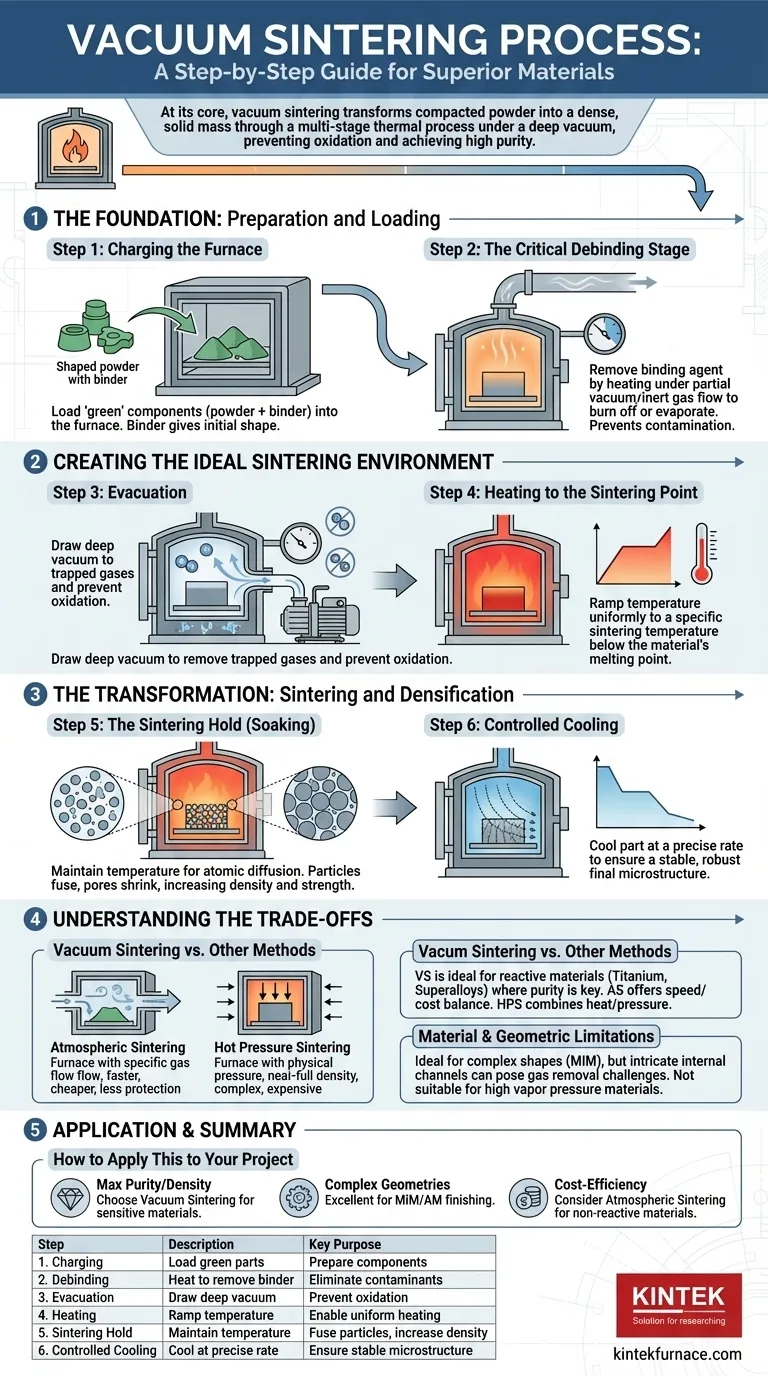

At its core, vacuum sintering is a multi-stage thermal process used to transform compacted powder into a dense, solid mass. The fundamental steps involve loading the material, removing binders and air, heating the material to just below its melting point, holding it at that temperature to allow atoms to bond, and finally, cooling it in a controlled manner. This entire sequence is performed within a vacuum to prevent oxidation and remove trapped gases, ensuring a final product with high purity and superior mechanical properties.

The goal of vacuum sintering is not merely to heat a material. It is to create a precisely controlled environment—devoid of oxygen and other contaminants—that enables atomic diffusion, effectively fusing powder particles together to achieve maximum density and strength.

The Foundation: Preparation and Loading

The success of the final sintered part is determined long before the furnace reaches its peak temperature. Proper preparation is paramount.

Step 1: Charging the Furnace

The process begins by loading the components into the furnace. These parts, often referred to as "green" parts, are typically formed from metal or ceramic powders mixed with a binding agent.

The binder gives the part its initial shape and handling strength before it undergoes the thermal process.

Step 2: The Critical Debinding Stage

Before high-temperature sintering can begin, the binding agent must be removed. This crucial step is called debinding.

The furnace is heated to a relatively low temperature, causing the binder to burn off or evaporate. This is often done under a partial vacuum or with a flow of inert gas to help carry the binder vapors away from the parts and out of the furnace.

Failing to remove the binder properly can lead to contamination, porosity, and defects in the final product.

Creating the Ideal Sintering Environment

With the part prepared, the next phase focuses on creating the perfect conditions for atoms to bond together. This is where the "vacuum" in vacuum sintering becomes essential.

Step 3: Evacuation

Once debinding is complete, the furnace is sealed and a deep vacuum is drawn. This serves two primary purposes.

First, removing air (specifically oxygen and nitrogen) prevents oxidation and other chemical reactions that would weaken the material. Second, the vacuum helps pull out any remaining trapped gases from within the part itself.

Step 4: Heating to the Sintering Point

The furnace temperature is then ramped up to the target sintering temperature. This temperature is specific to each material but is always below its melting point.

The rate of heating is carefully controlled to ensure the part heats uniformly, preventing thermal stress that could cause cracking.

The Transformation: Sintering and Densification

This is the phase where the material fundamentally changes from a porous compact into a dense, solid object.

Step 5: The Sintering Hold (Soaking)

The material is held at the sintering temperature for a specific duration, a period known as the "hold" or "soak" time.

During this time, atomic diffusion occurs. Atoms migrate across the boundaries of the individual powder particles, causing the particles to fuse and the pores between them to shrink or close entirely. This is what increases the part's density and strength.

Step 6: Controlled Cooling

After the hold time is complete, the part is cooled back to room temperature. Like the heating ramp, the cooling rate is also precisely controlled.

Rapid cooling can introduce internal stresses and create a brittle microstructure, while slow, controlled cooling helps ensure a stable and robust final part.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Vacuum sintering is a powerful process, but it is not the only option, nor is it always the best one. Understanding its context is key to making an informed decision.

Vacuum Sintering vs. Other Methods

The main alternative is atmospheric sintering, where the process occurs in a furnace filled with a specific gas (like nitrogen or argon). This can be faster and cheaper but offers less protection against trace contaminants.

Another related process is hot pressing, which combines heat, vacuum, and intense physical pressure. Hot pressing can achieve near-full density but is typically limited to simpler geometries and is more expensive. Vacuum sintering relies on atomic diffusion alone, without external pressure.

Material and Geometric Limitations

Vacuum sintering is ideal for reactive materials like titanium, stainless steels, and superalloys that are highly sensitive to oxygen. However, some materials with very high vapor pressures may not be suitable for a deep vacuum environment.

While capable of producing complex shapes (especially when combined with binder jetting or metal injection molding), extremely intricate internal channels can sometimes pose challenges for uniform gas removal and binder burnout.

How to Apply This to Your Project

Choosing the right thermal process depends entirely on the requirements of your final component.

- If your primary focus is maximum purity and density: Vacuum sintering is the superior choice, as it provides an unmatched environment for eliminating oxidation and porosity in sensitive materials.

- If your primary focus is producing complex geometries: Vacuum sintering is an excellent finishing step for parts made via Metal Injection Molding (MIM) or additive manufacturing, where binder removal and densification are critical.

- If your primary focus is cost-efficiency for non-reactive materials: You may find that atmospheric sintering in a controlled gas environment provides an acceptable balance of performance and cost.

Ultimately, mastering the steps of vacuum sintering allows you to engineer materials at the atomic level, achieving properties that are impossible through other methods.

Summary Table:

| Step | Description | Key Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Charging | Load green parts into furnace | Prepare components for sintering |

| 2. Debinding | Heat to remove binder under vacuum or inert gas | Eliminate contaminants and prevent defects |

| 3. Evacuation | Draw deep vacuum in sealed furnace | Prevent oxidation and remove trapped gases |

| 4. Heating | Ramp temperature to sintering point | Enable uniform heating for atomic bonding |

| 5. Sintering Hold | Maintain temperature for atomic diffusion | Fuse particles to increase density and strength |

| 6. Controlled Cooling | Cool part at precise rate | Ensure stable microstructure and reduce stresses |

Ready to achieve superior material purity and density with custom vacuum sintering solutions? At KINTEK, we leverage exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnaces, including Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, tailored for industries like aerospace, medical devices, and additive manufacturing. Our deep customization capabilities ensure your unique experimental requirements are met precisely. Contact us today to discuss how our solutions can enhance your lab's efficiency and product quality—get in touch now!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the purpose of a 1400°C heat treatment for porous tungsten? Essential Steps for Structural Reinforcement

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- Why is a high-vacuum environment necessary for sintering Cu/Ti3SiC2/C/MWCNTs composites? Achieve Material Purity

- What tasks does a high-temperature vacuum sintering furnace perform for PEM magnets? Achieve Peak Density

- What are the benefits of using a high-temperature vacuum furnace for the annealing of ZnSeO3 nanocrystals?