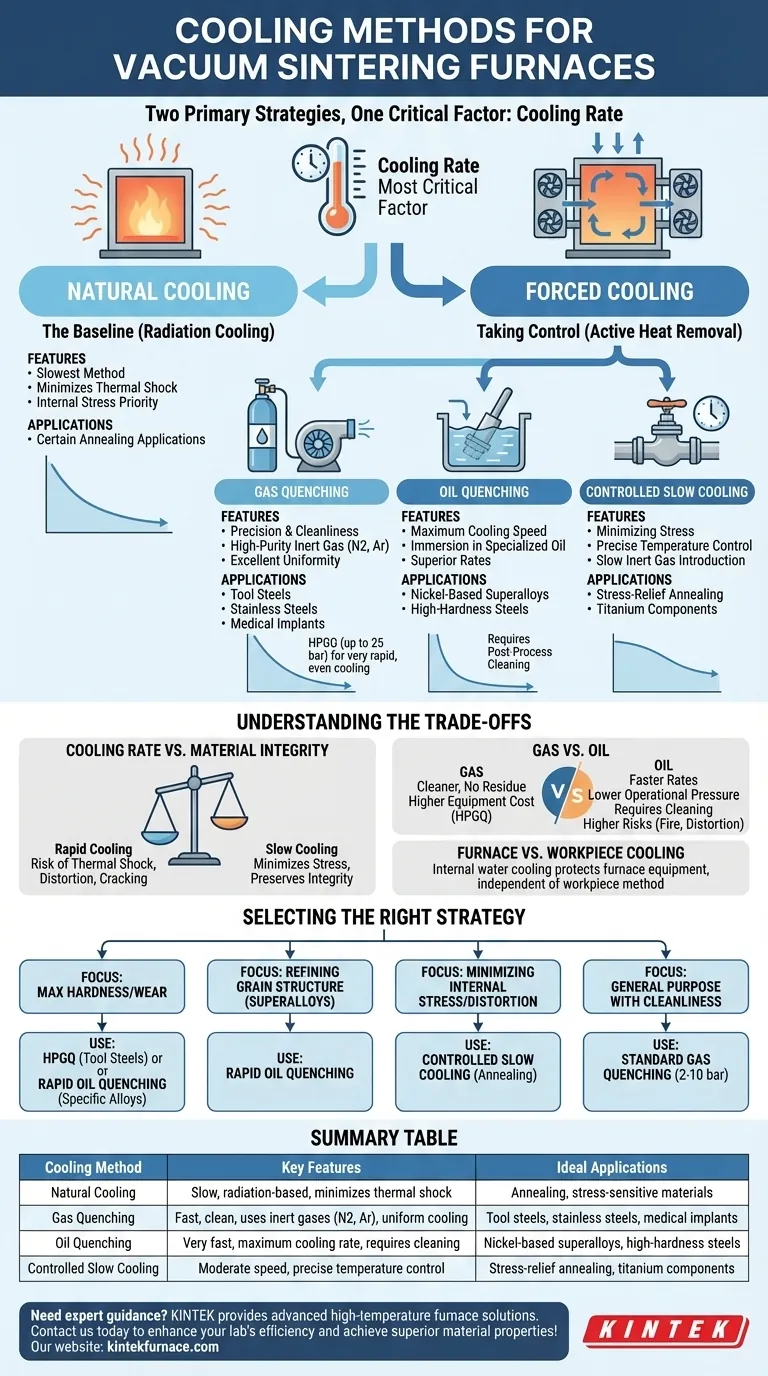

At its core, a vacuum sintering furnace utilizes two primary cooling strategies: natural cooling and forced cooling. Forced cooling, the more common and controllable method, is further divided into specific techniques like gas quenching and oil quenching, which are selected based on the material being processed and the desired final properties.

The most critical factor in choosing a cooling method is not the method itself, but the desired cooling rate. This rate directly determines the final microstructure, hardness, and internal stresses of the sintered component.

The Fundamental Approaches: Natural vs. Forced Cooling

The initial choice you will make is between letting the furnace cool on its own or actively accelerating the process. This decision establishes the foundation for your entire cooling strategy.

Natural Cooling: The Baseline

Natural cooling, also known as radiation cooling, involves simply turning off the heating elements and allowing the furnace and its contents to cool down naturally through heat radiation within the vacuum.

This is the slowest method available. It is typically reserved for processes where minimizing thermal shock and internal stress is the absolute priority, such as in certain annealing applications.

Forced Cooling: Taking Control

Forced cooling actively removes heat from the workpiece to achieve a specific, rapid cooling rate. This is accomplished by backfilling the vacuum chamber with a cooling medium that circulates around the parts.

This method is essential for achieving specific metallurgical properties, like hardness in tool steels or a refined grain structure in superalloys. It is the standard for most modern industrial sintering applications.

Key Forced Cooling Methods and Media

Once you decide on forced cooling, the next choice is the medium and mechanism used to transfer the heat. This is where you gain precise control over the final outcome.

Gas Quenching: Precision and Cleanliness

Gas quenching involves introducing a high-purity inert gas, typically nitrogen or argon, into the hot zone at controlled pressures. A fan or blower then circulates this gas to transfer heat away from the parts and to a heat exchanger.

This method offers excellent uniformity and prevents contamination, making it ideal for high-value components like tool steels, stainless steels, and medical implants. High-Pressure Gas Quenching (HPGQ) uses pressures up to 25 bar to achieve very rapid and even cooling.

Oil Quenching: Maximum Cooling Speed

For materials that require the fastest possible cooling rates to achieve their properties, oil quenching is used. In this process, the hot workload is immersed in a specialized quenching oil.

This technique is common for refining the grain structure in nickel-based superalloys or achieving maximum hardness in certain types of steel. The downside is the need for post-process part cleaning.

Controlled Slow Cooling: Minimizing Stress

This is a variation of forced cooling where inert gas is used not for speed, but for precise temperature control. The gas is introduced slowly, providing a cooling rate that is faster than natural cooling but slow enough to prevent distortion.

This is the preferred method for stress-relief annealing of sensitive materials like titanium components, where dimensional stability is more important than hardness.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Selecting a cooling method involves balancing speed, cost, and the risk of damaging the component. A faster cool-down is not always better.

Cooling Rate vs. Material Integrity

The primary risk of any rapid cooling method is thermal shock. If a part is cooled too quickly or unevenly, it can lead to internal stress, distortion, or even cracking. This is especially true for parts with complex geometries or varying thicknesses.

Gas vs. Oil: The Operational Differences

Gas quenching is a cleaner process, leaving no residue on the parts. However, achieving extremely high cooling rates requires high-pressure systems, which increases equipment complexity and cost.

Oil quenching provides superior cooling rates at a lower operational pressure but necessitates a post-quenching cleaning process to remove oil residue. There is also a higher risk of fire and part distortion if not properly controlled.

Furnace Cooling vs. Workpiece Cooling

It is critical to distinguish between cooling the workpiece and cooling the furnace itself. Many furnaces incorporate an internal water cooling system to protect components like the chamber walls and power feedthroughs from overheating.

This equipment-cooling system operates independently of the workpiece quenching method (gas or oil) and is vital for the furnace's long-term stability and operational safety.

Selecting the Right Cooling Strategy

Your choice must be driven by the specific metallurgical goal for your material. Each method is a tool designed for a different outcome.

- If your primary focus is maximum hardness and wear resistance: Use High-Pressure Gas Quenching (HPGQ) for tool steels or rapid oil quenching for specific alloys that demand the fastest cool-down.

- If your primary focus is refining grain structure in superalloys: Use rapid oil quenching, as its heat transfer capability is often necessary to achieve the desired metallurgical transformation.

- If your primary focus is minimizing internal stress and distortion: Use controlled slow cooling with an inert gas backfill, which is ideal for annealing and stress-relieving processes.

- If your primary focus is general-purpose processing with cleanliness: Standard gas quenching (2-10 bar) provides a versatile balance of speed and control for a wide range of materials.

Understanding these principles empowers you to transform the cooling phase from a simple necessity into a precise engineering tool.

Summary Table:

| Cooling Method | Key Features | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Cooling | Slow, radiation-based, minimizes thermal shock | Annealing, stress-sensitive materials |

| Gas Quenching | Fast, clean, uses inert gases (N2, Ar), uniform cooling | Tool steels, stainless steels, medical implants |

| Oil Quenching | Very fast, maximum cooling rate, requires cleaning | Nickel-based superalloys, high-hardness steels |

| Controlled Slow Cooling | Moderate speed, precise temperature control | Stress-relief annealing, titanium components |

Need expert guidance on selecting the right cooling method for your vacuum sintering process? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnace solutions, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we can precisely meet your unique experimental requirements. Contact us today to enhance your lab's efficiency and achieve superior material properties!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 1700℃ Controlled Inert Nitrogen Atmosphere Furnace

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- Why is a high-vacuum environment necessary for sintering Cu/Ti3SiC2/C/MWCNTs composites? Achieve Material Purity

- How does the ultra-low oxygen environment of vacuum sintering affect titanium composites? Unlock Advanced Phase Control

- What is the purpose of a 1400°C heat treatment for porous tungsten? Essential Steps for Structural Reinforcement

- Why is a high vacuum essential for Ti-6Al-4V sintering? Protect Your Alloys from Embrittlement

- What tasks does a high-temperature vacuum sintering furnace perform for PEM magnets? Achieve Peak Density