At its core, the Curie temperature is a critical threshold where a magnetic material's properties fundamentally change, causing a dramatic and sudden drop in induction heating efficiency. Below this temperature (around 770°C or 1420°F for steel), the material is magnetic and heats rapidly; above it, it becomes non-magnetic, and the heating rate decreases significantly.

Understanding the Curie point isn't just an academic exercise; it is the key to controlling heat distribution, managing energy efficiency, and achieving predictable results in processes like hardening, forging, and tempering.

The Two Engines of Induction Heating

To grasp the impact of the Curie temperature, you must first understand that induction heating in ferromagnetic materials like iron and steel is driven by two distinct mechanisms working in parallel.

Eddy Current Heating

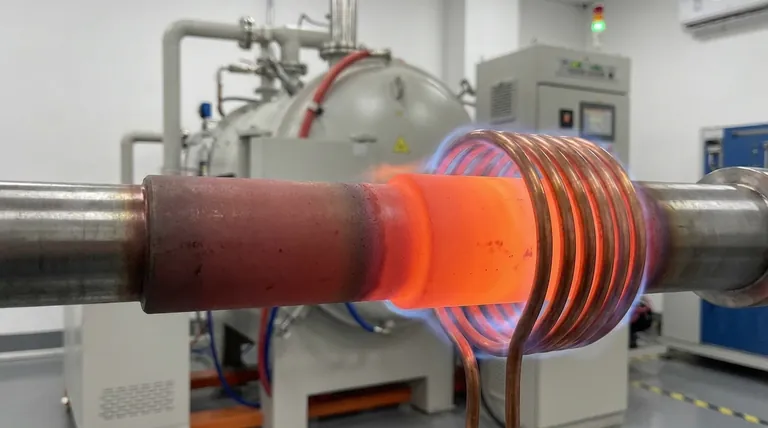

An induction coil generates a powerful, rapidly alternating magnetic field. When you place a conductive workpiece, like a steel shaft, inside this field, it induces circular electrical currents within the part.

These currents, known as eddy currents, flow against the material's natural electrical resistance. This resistance creates friction, which generates precise and intense heat (known as Joule or I²R heating). This is the primary heating method for all conductive materials, including non-magnetic ones like aluminum and copper.

Hysteresis Heating: The Magnetic Bonus

Ferromagnetic materials have an additional, powerful heating mechanism. These materials are composed of tiny magnetic regions called domains.

When exposed to the induction coil's alternating magnetic field, these domains rapidly flip their magnetic polarity, trying to align with the field. This constant, high-speed internal friction generates a significant amount of heat. Think of it as the heat generated by rapidly bending a paperclip back and forth. This hysteresis heating only occurs in magnetic materials and acts as a powerful supplement to eddy currents.

What Happens at the Curie Temperature?

The Curie temperature is the point of phase transition. When a ferromagnetic material reaches this temperature, its atomic structure changes, and it abruptly loses its magnetic properties, becoming paramagnetic. This has two immediate and critical consequences.

Hysteresis Heating Vanishes

Because the material is no longer magnetic, the magnetic domains cease to exist. The "magnetic bonus" from hysteresis heating stops instantly.

This is the primary reason for the sudden drop in heating efficiency. You have effectively turned off one of the two engines driving the heating process.

Permeability and Penetration Depth Shift

Magnetic permeability is a measure of how easily a material can support the formation of a magnetic field. Below the Curie point, steel has a high permeability, which concentrates the magnetic field and the resulting eddy currents very close to the part's surface.

At the Curie temperature, permeability plummets to a value near that of open air. The magnetic field is no longer concentrated at the surface and instead penetrates much deeper into the part. This causes the eddy currents to spread out over a larger volume, drastically reducing the heating intensity at the surface.

Understanding the Practical Implications

This transition from efficient surface heating to less efficient deep heating is not just a theoretical curiosity; it has profound effects on real-world applications.

The Inevitable Efficiency Drop

When a workpiece crosses its Curie temperature, your power supply must work harder to deliver heat into the part. The loss of hysteresis and the deeper penetration of eddy currents mean that for the same power input, the rate of temperature rise will slow down considerably.

The Self-Regulating Effect

This efficiency drop can be a significant advantage. Because heating becomes much less effective above the Curie point, the material has a natural tendency to "stall" at this temperature.

This self-regulating behavior is extremely useful for processes like adhesive curing or tempering, where the goal is to bring a part to a uniform temperature and hold it there without complex temperature controllers or the risk of overheating.

The Challenge for Surface Hardening

For case hardening, the goal is to rapidly heat the surface layer to its hardening temperature while keeping the core cool. The Curie effect presents a challenge here.

As the surface passes the Curie point, the heating efficiency drops, and the heat begins to penetrate deeper. To achieve a shallow, hard case, you must use a very high frequency and enough power to push through this transition zone quickly before the core has time to heat up via thermal conduction.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Controlling your process requires anticipating the material's transition across the Curie temperature.

- If your primary focus is surface hardening: Use a high frequency and sufficient power to overcome the efficiency drop at the Curie point and minimize heat soak into the core.

- If your primary focus is uniform through-heating or forging: Use a lower frequency that provides deep heat penetration from the start, and plan for a longer heating cycle to account for the change in efficiency.

- If your primary focus is holding a precise temperature: Leverage the self-regulating nature of the Curie point as a passive form of temperature control, particularly for processes below 800°C.

Mastering induction heating means treating the Curie temperature not as an obstacle, but as a predictable variable you can use to your advantage.

Summary Table:

| Aspect | Below Curie Temperature | Above Curie Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Properties | Magnetic (ferromagnetic) | Non-magnetic (paramagnetic) |

| Heating Mechanisms | Eddy currents and hysteresis heating | Only eddy current heating |

| Heating Efficiency | High due to combined mechanisms | Drops significantly |

| Penetration Depth | Shallow, concentrated at surface | Deeper, spread out |

| Common Applications | Surface hardening, rapid heating | Uniform heating, tempering, forging |

Optimize your induction heating processes with KINTEK's advanced solutions! Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with high-temperature furnace systems like Muffle, Tube, Rotary, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures precise alignment with your unique experimental needs, enhancing efficiency and results. Contact us today to discuss how we can support your specific applications!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press Tube Furnace

People Also Ask

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- Why is a high-vacuum environment necessary for sintering Cu/Ti3SiC2/C/MWCNTs composites? Achieve Material Purity

- What is the role of vacuum pumps in a vacuum heat treatment furnace? Unlock Superior Metallurgy with Controlled Environments

- What is the purpose of a 1400°C heat treatment for porous tungsten? Essential Steps for Structural Reinforcement

- What is the purpose of setting a mid-temperature dwell stage? Eliminate Defects in Vacuum Sintering