In materials science, quenching is a controlled process of rapidly cooling a heated metal or alloy. This is not simply about making a hot component cold; it is a precise heat treatment that fundamentally transforms the material's internal microscopic structure. This transformation is used to lock in desirable mechanical properties like extreme hardness and strength that would be unattainable through slower cooling.

Quenching's primary purpose is to freeze a material in a high-temperature, unstable structural state, preventing its atoms from rearranging into their natural, softer form. In essence, you are trading the material's natural ductility for a significant and engineered increase in hardness and strength.

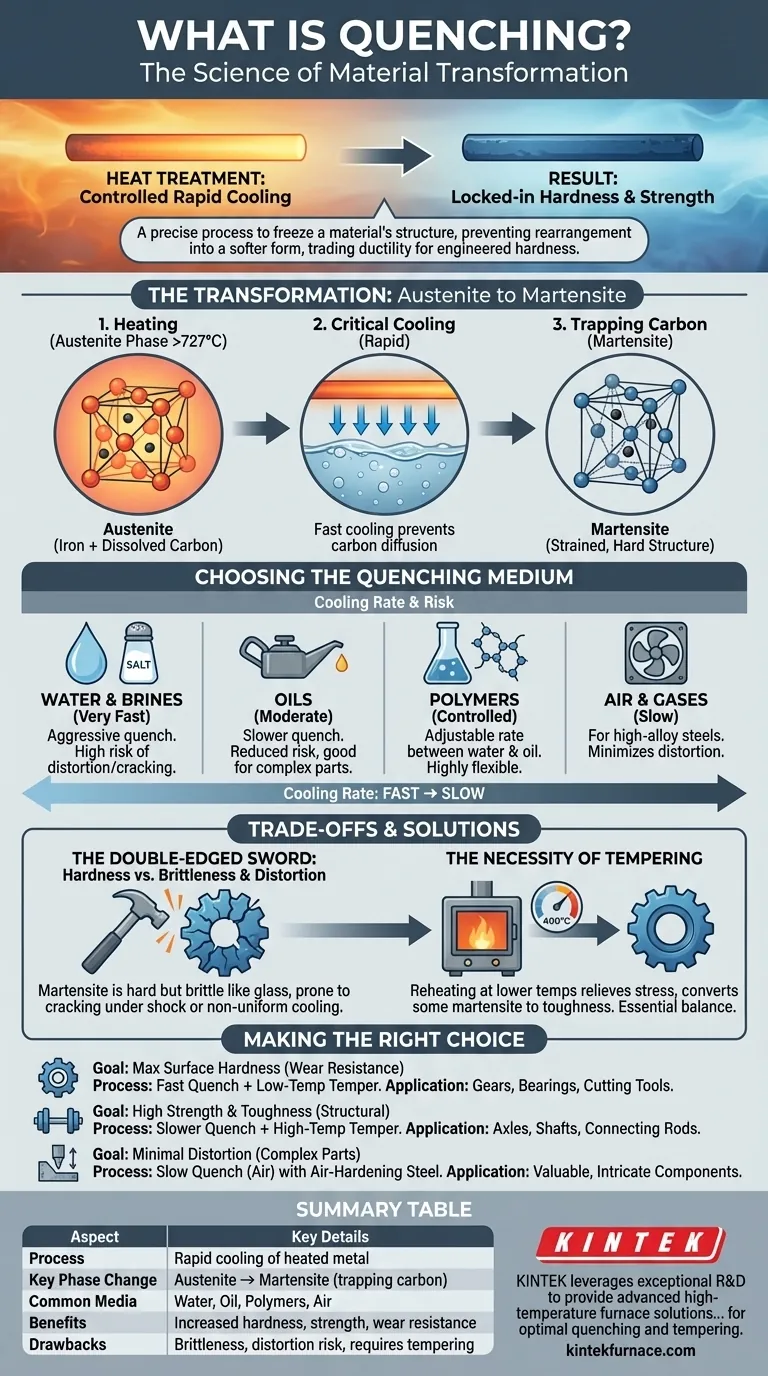

The Science of Transformation: From Austenite to Martensite

Quenching is a feat of materials engineering that manipulates the crystalline structure of a metal at the atomic level. The process forces the material into a state it would not naturally assume.

Heating to the Austenitic Phase

First, a steel component is heated to a specific critical temperature, typically above 727°C (1340°F). At this temperature, its iron atoms rearrange into a crystal structure known as austenite. A key feature of austenite is its ability to dissolve carbon atoms within its lattice.

The Critical Cooling Rate

The "rapid cooling" of quenching is the most critical step. The goal is to cool the material so quickly that the dissolved carbon atoms do not have time to diffuse out of the iron crystal lattice as it attempts to change back to its room-temperature form.

Trapping Carbon to Form Martensite

When cooling is sufficiently fast, the carbon becomes trapped. This forces the iron crystals into a new, highly strained, and distorted structure called martensite. This immense internal strain is what makes martensite exceptionally hard, strong, and also very brittle. It is the atomic-level source of the properties that quenching imparts.

Choosing the Right Quenching Medium

The choice of quenching medium is critical because it dictates the cooling rate. The correct medium is selected based on the type of steel, the component's size and geometry, and the desired final properties.

Water and Brines

Water provides a very fast and aggressive quench. Adding salt to create a brine solution makes it even faster by disrupting the insulating vapor blanket that can form around the part. This method is effective but carries a high risk of causing the part to distort or crack.

Oils

Oils cool a component significantly slower than water. This less severe quench reduces the risk of cracking and distortion, making it a common choice for alloy steels and parts with more complex geometries.

Polymers

Polymer quenchants are solutions of a polymer in water. By adjusting the concentration of the polymer, the cooling rate can be precisely controlled to a level between that of water and oil, offering a highly flexible and modern solution.

Air and Gases

For certain high-alloy steels (like many tool steels), the transformation to martensite can be achieved with a much slower cooling rate. For these materials, a quench in still or forced air is sufficient, which dramatically minimizes the risk of distortion.

Understanding the Trade-offs: The Double-Edged Sword of Hardness

While quenching achieves exceptional hardness, this property does not come without significant compromises. A component that is only quenched is often unfit for its final purpose.

Brittleness: The Price of Hardness

The martensitic structure created by quenching is not just hard; it is also extremely brittle, similar to glass. An impact or shock that a softer material would absorb could easily shatter a part that has only been quenched.

The Risk of Distortion and Cracking

The rapid cooling is never perfectly uniform. Thinner sections of a part cool faster than thicker sections, creating immense internal stresses. These stresses can cause the component to warp, bend, or, in severe cases, crack during the quenching process itself.

The Necessity of Tempering

Because of the extreme brittleness, a quenched part is almost always tempered. Tempering involves reheating the component to a much lower temperature (e.g., 200-650°C or 400-1200°F) and holding it for a set time. This process relieves internal stresses and converts some of the brittle martensite into a tougher structure, trading a small amount of hardness for a crucial gain in toughness.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The decision to use quenching, and the specific process chosen, must be directly aligned with the final application of the component.

- If your primary focus is maximum surface hardness for wear resistance: A fast quench (water or brine) followed by a low-temperature temper is ideal for components like gears, bearings, or cutting tools.

- If your primary focus is high strength and toughness for structural integrity: A slower, less severe quench (oil or polymer) followed by a higher-temperature temper is required for parts like axles, shafts, or connecting rods.

- If your primary focus is minimizing distortion in a complex or valuable part: Using a very slow quench medium like air, which requires a specialized "air-hardening" steel alloy, is the safest and most stable approach.

Ultimately, quenching is not just a cooling step but a critical engineering lever used to precisely tailor a material's properties for its intended purpose.

Summary Table:

| Aspect | Key Details |

|---|---|

| Process | Rapid cooling of heated metal to lock in high-temperature structure |

| Key Phase Change | Austenite transforms to martensite, trapping carbon for hardness |

| Common Media | Water (fast), Oil (moderate), Polymers (controlled), Air (slow) |

| Benefits | Increased hardness, strength, and wear resistance |

| Drawbacks | Brittleness, risk of distortion/cracking, requires tempering |

| Applications | Gears, cutting tools, axles, and other high-performance components |

Need precise heat treatment solutions for your laboratory? KINTEK leverages exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing to provide advanced high-temperature furnace solutions, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. With strong deep customization capabilities, we tailor our products to meet your unique experimental requirements, ensuring optimal quenching and tempering processes for enhanced material properties. Contact us today to discuss how we can support your research and development goals!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace with Bottom Lifting

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1700℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Multi Zone Laboratory Quartz Tube Furnace Tubular Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is the role of a muffle furnace in the study of biochar regeneration and reuse? Unlock Sustainable Water Treatment

- What is the primary function of a muffle furnace for BaTiO3? Master High-Temp Calcination for Ceramic Synthesis

- Why is a high-performance muffle furnace required for the calcination of nanopowders? Achieve Pure Nanocrystals

- What role does a muffle furnace play in the preparation of MgO support materials? Master Catalyst Activation

- What environmental conditions are critical for SiOC ceramicization? Master Precise Oxidation & Thermal Control