Vacuum heat treating achieves precise temperature and time control by using programmable controllers to manage heating elements and inert gas quenching systems within a controlled, airless environment. Specialized sensors called thermocouples provide real-time feedback, allowing the system to execute a pre-defined "recipe" of heating rates, hold times, and cooling rates with exceptional accuracy.

The power of vacuum heat treating lies not just in preventing surface contamination, but in creating a stable, predictable environment. This allows for the exact manipulation of a material's temperature and soak time, which directly dictates its final crystalline structure and mechanical properties.

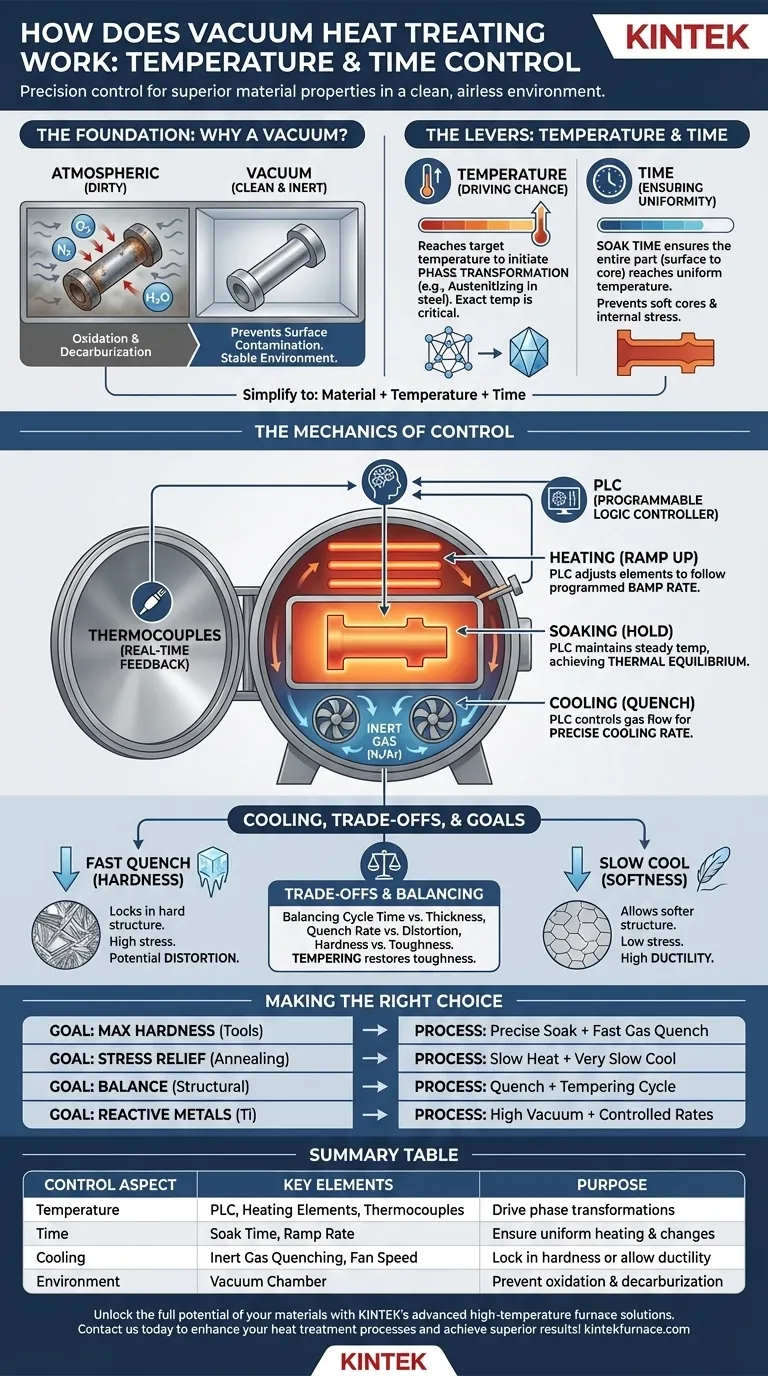

The Core Principles of Control

To understand how the process is controlled, you must first understand why such precision is necessary. The vacuum environment is the foundation that makes repeatable, exact thermal processing possible.

Why a Vacuum? The Foundation of Control

A vacuum furnace removes atmospheric gases—primarily oxygen, nitrogen, and water vapor. This prevents unwanted chemical reactions like oxidation (rust) and decarburization (loss of carbon from the surface) that would otherwise occur at high temperatures.

By creating this inert environment, the process is simplified to a pure relationship between the material, temperature, and time. There are no atmospheric variables to compromise the outcome.

The Role of Temperature: Driving Microstructural Change

Every heat treatment process is designed to reach a specific target temperature that initiates a phase transformation in the metal's crystalline structure.

For steel, this often means heating to its austenitizing temperature, where the crystal structure changes into a form called austenite, which can absorb carbon. The exact temperature is critical; being off by even a small amount can result in an incomplete transformation and failed parts.

The Importance of Time: Ensuring Uniform Transformation

Once the target temperature is reached, it must be held for a specific duration, known as the soak time. This ensures the entire part—from the thin surface to the thick core—reaches a uniform temperature.

If the soak time is too short, only the outer shell of the part will transform, leaving a soft core. This creates inconsistent hardness and internal stresses, leading to premature failure.

The Mechanics of Control

Modern vacuum furnaces are highly automated systems designed to execute thermal recipes with minimal deviation.

Heating: Precision Through Programmable Logic

The process is governed by a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC), which is the brain of the furnace. It controls the power sent to the internal heating elements (often made of graphite or molybdenum).

Thermocouples placed strategically within the furnace measure the temperature of the parts and the chamber. This data is fed back to the PLC, which adjusts the heating elements to precisely follow the programmed heating rate, or ramp rate.

Soaking: Achieving Thermal Equilibrium

During the soak phase, the PLC's job is to hold the temperature perfectly steady. It constantly monitors the thermocouple readings and makes micro-adjustments to the heating elements to counteract any heat loss. This ensures the part achieves complete thermal and metallurgical equilibrium.

Cooling (Quenching): Locking in the Properties

The rate of cooling is just as critical as the heating. The PLC manages this by controlling the introduction of a high-purity inert gas, like nitrogen or argon, into the chamber.

A fast quench, driven by powerful fans circulating the gas, "locks in" a hard, brittle microstructure (like martensite in steel). A slow cool, with no gas assist, allows a softer, more ductile structure to form. This control over the cooling rate is what determines the final balance of hardness and toughness.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While powerful, the vacuum heat treating process involves balancing competing factors to achieve the desired result.

Cycle Time vs. Part Thickness

Thicker and more massive parts require significantly longer soak times to become heated through. This directly increases the total furnace cycle time, which in turn increases processing costs.

Quench Rate vs. Distortion

A very rapid gas quench is necessary for maximum hardness, but it also induces significant thermal stress. In parts with complex geometries or sharp corners, this stress can cause warping, distortion, or even cracking. The quench rate must often be moderated to balance hardness goals with the physical integrity of the part.

Hardness vs. Toughness

The fundamental trade-off in heat treating is between hardness and toughness. A fast quench that yields high hardness also results in lower ductility and toughness (brittleness). A subsequent, lower-temperature process called tempering is often required to restore some toughness, which slightly reduces the peak hardness.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The specific time and temperature profile you use is entirely dependent on your end goal for the material.

- If your primary focus is maximum hardness (e.g., for cutting tools): You will use a precise soak at the austenitizing temperature followed by the fastest possible inert gas quench to form martensite.

- If your primary focus is stress relief and softness (e.g., annealing): You will use a slow heating cycle and a very slow, controlled cool-down within the vacuum to produce the softest possible microstructure.

- If your primary focus is balancing hardness and toughness (e.g., structural components): You will perform a hardening quench followed by a precise tempering cycle, where the part is reheated to a much lower temperature to reduce brittleness.

- If you are working with reactive metals (e.g., titanium or specialty alloys): Your process will require a high vacuum and carefully controlled, often slower, heating and cooling rates to prevent both contamination and thermal shock.

Ultimately, mastering vacuum heat treating is understanding that temperature and time are the fundamental levers for dictating a material's final form and function.

Summary Table:

| Control Aspect | Key Elements | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Programmable Logic Controller (PLC), Heating Elements, Thermocouples | Drive phase transformations in materials, e.g., austenitizing for steel |

| Time | Soak Time, Ramp Rate | Ensure uniform heating and complete microstructural changes |

| Cooling | Inert Gas Quenching, Fan Speed | Lock in hardness or allow ductility based on quench rate |

| Environment | Vacuum Chamber | Prevent oxidation and decarburization for pure thermal control |

Unlock the full potential of your materials with KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnace solutions. Leveraging exceptional R&D and in-house manufacturing, we provide diverse laboratories with precise vacuum heat treating systems, including Muffle, Tube, Rotary Furnaces, Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, and CVD/PECVD Systems. Our strong deep customization capability ensures we meet your unique experimental requirements for optimal temperature and time control. Contact us today to discuss how we can enhance your heat treatment processes and achieve superior results!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

People Also Ask

- What is the vacuum heat treatment process? Achieve Superior Surface Quality and Material Performance

- What are the proper procedures for handling the furnace door and samples in a vacuum furnace? Ensure Process Integrity & Safety

- What are the benefits of vacuum heat treatment? Achieve Superior Metallurgical Control

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in LP-DED? Optimize Alloy Integrity Today