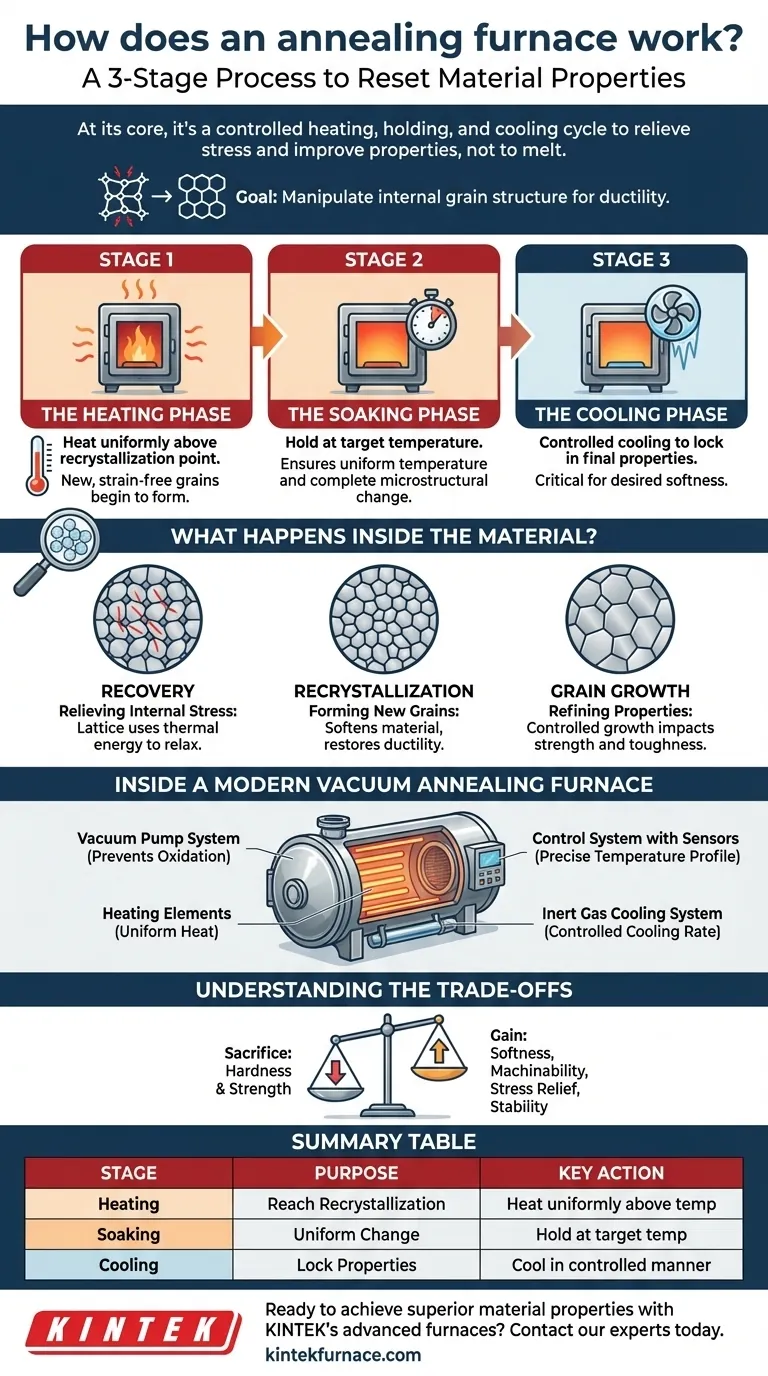

At its core, an annealing furnace operates on a simple principle: heat a material, hold it at a specific temperature, and then cool it in a controlled manner. This three-stage process is not about melting the material, but about heating it just enough—above its recrystallization temperature—to fundamentally reset its internal structure, relieving stress and improving its properties.

The true purpose of annealing is not merely to heat and cool a metal. It is a precise metallurgical process designed to manipulate a material's internal grain structure, trading hardness for ductility and removing internal stresses to prevent future failure.

The Three Foundational Stages of Annealing

An annealing furnace executes a carefully timed thermal cycle. Each stage serves a distinct purpose in altering the material's microstructure.

Stage 1: The Heating Phase

The process begins by heating the material at a controlled rate. The goal is to bring the entire workpiece uniformly to a target temperature that is above its recrystallization point.

This is the temperature at which new, strain-free grains can begin to form within the material's internal lattice. Precise temperature control is critical to avoid overheating or uneven heating.

Stage 2: The Soaking Phase

Once the target temperature is reached, the material is "soaked" or held at that temperature for a specific duration. The length of this stage depends on the material type, its thickness, and the desired outcome.

Soaking ensures that the temperature is uniform throughout the material's entire cross-section and allows the necessary microstructural changes to complete.

Stage 3: The Cooling Phase

Finally, the material is cooled in a highly controlled manner. The cooling rate is arguably the most critical variable, as it locks in the final properties of the material.

Cooling can be slow (leaving the workpiece in the furnace as it cools) or faster (using inert gas or water cooling systems), depending on the desired level of softness and grain size.

What Happens Inside the Material?

While the furnace executes its thermal program, the material itself undergoes a transformation on a microscopic level.

Recovery: Relieving Internal Stress

As the temperature first rises, the material enters the recovery stage. At this point, the crystal lattice has enough thermal energy to begin relieving internal stresses that were induced by prior work like casting, forging, or welding. This prevents future warping or cracking.

Recrystallization: Forming New Grains

As the temperature continues to rise past the recrystallization point, new, strain-free crystals (or "grains") begin to nucleate and grow. These new grains replace the old, deformed ones that were full of stress and dislocations. This is the primary mechanism that softens the material and restores its ductility.

Grain Growth: Refining the Final Properties

If the material is held at the annealing temperature for too long, the new, strain-free grains will continue to grow larger. Controlling this grain growth is essential, as grain size has a direct impact on mechanical properties like strength and toughness.

Inside a Modern Vacuum Annealing Furnace

Many modern annealing processes use a vacuum furnace to achieve superior results by protecting the material from the outside atmosphere.

The Furnace Body and Vacuum System

The process takes place within a sealed, vacuum-tight chamber. A system of mechanical and diffusion pumps removes air from the chamber before heating begins. This creates a vacuum that prevents oxidation and surface contamination, resulting in a clean, bright finish on the workpiece.

The Heating and Control Systems

Heating elements are positioned to provide uniform heat through radiation and convection. A sophisticated control system uses temperature sensors (thermocouples) to monitor the workpiece in real time, adjusting the power to the elements to precisely follow the programmed heating and soaking profile.

The Cooling System

After the soaking stage, the furnace can initiate a controlled cooling cycle. In a vacuum furnace, this often involves back-filling the chamber with a high-purity inert gas like argon or nitrogen, which is then circulated by a fan to cool the workpiece faster than natural cooling would allow.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Annealing is a powerful tool, but it involves clear trade-offs. The primary goal is almost always to sacrifice hardness to gain other desirable properties.

The Main Benefit: Softness and Machinability

The most common reason to anneal a material is to make it softer and more ductile. This significantly improves its machinability, reducing tool wear and making it easier to cut, form, or draw.

The Key Purpose: Stress Relief and Stability

For components that have been welded, forged, or cold-worked, annealing is critical for relieving residual internal stresses. This stabilizes the part, preventing distortion or cracking that might occur over time or during subsequent processing.

The Inherent Drawback: Reduced Hardness and Strength

The process of recrystallization that softens the material also inherently reduces its tensile strength and hardness. Annealing is fundamentally the opposite of hardening treatments like quenching.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Annealing should be applied strategically based on the final objective for the material.

- If your primary focus is preparing a material for extensive machining: Use a full anneal to achieve maximum softness and ductility, prioritizing ease of cutting over final strength.

- If your primary focus is preventing deformation in a complex assembly: Use a stress-relief anneal at a lower temperature to remove internal stresses without significantly altering the core mechanical properties.

- If your primary focus is optimizing a material for a final heat treatment: Use annealing to create a uniform, refined grain structure that will respond predictably to subsequent quenching and tempering.

Ultimately, annealing provides you with precise control to reset a material's properties, making it a foundational tool for advanced manufacturing.

Summary Table:

| Stage | Purpose | Key Action |

|---|---|---|

| Heating | Reach Recrystallization | Heat material uniformly above its recrystallization temperature. |

| Soaking | Uniform Microstructural Change | Hold at target temperature to allow complete transformation. |

| Cooling | Lock in Final Properties | Cool in a controlled manner to set the material's new properties. |

Ready to achieve superior material properties with a precision annealing furnace?

KINTEK's advanced high-temperature furnace solutions, including our Vacuum & Atmosphere Furnaces, are engineered for exceptional control and uniformity. Leveraging our strong in-house R&D and manufacturing capabilities, we provide deep customization to meet your unique annealing requirements—whether for stress relief, improved machinability, or preparing materials for further heat treatment.

Contact our experts today to discuss how a KINTEK furnace can enhance your laboratory's capabilities and manufacturing outcomes.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Furnace with Pressure for Vacuum Sintering

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the functions of a high-vacuum furnace for CoReCr alloys? Achieve Microstructural Precision and Phase Stability

- What are the general operational features of a vacuum furnace? Achieve Superior Material Purity & Precision

- What role does a high-temperature vacuum heat treatment furnace play in TBC post-processing? Enhance Coating Adhesion

- What are the proper procedures for handling the furnace door and samples in a vacuum furnace? Ensure Process Integrity & Safety

- How does a vacuum heat treatment furnace influence Ti-6Al-4V microstructure? Optimize Ductility and Fatigue Resistance